Ako a smaller city in Japan that is perfect for a short stay if you are looking for an off-the-beaten-track destination away from the crowds of more popular tourist areas like Kyoto or Hiroshima. Although Ako may not be so well-known among foreign visitors, it has much to offer for those interested in Japanese history and culture. Not only is Ako a great place to admire traditional Japanese architecture and learn about old methods of salt production, but it was also the home domain of one of the most famous samurai groups in Japanese history, the 47 Ronin.

The Real-Life Events and History of the 47 Ronin of Ako

The famous story of the 47 Ronin (ronin 浪人 are masterless samurai), which is known by most Japanese under the name Chushingura (忠臣蔵), is based on the real events of the Ako incident (赤穂事件), that took place in the early 18th century. This incident inspired numerous plays, novels, and movies up to this day. It was even adapted by Hollywood in the 2013 film “47 Ronin,” starring Keanu Reeves together with internationally famous Japanese actors, such as Sanada Hiroyuki and Kikuchi Rinko.

In 1675, Asano Naganori became the lord of Ako Domain when he was just 9 years old after his father’s death. As it was common for lords of smaller domains, he was appointed to temporary minor offices by the Tokugawa Shogunate several times. In 1701, he was appointed to serve as an official under Kira Yoshinaka to host the emissaries from the imperial court at Edo Castle. Yoshinaka was in charge of teaching him the correct court manners for this occasion, but he looked down on him and treated him quite harshly. The tension between the two men grew day by day. When Yoshinaka rudely insulted Naganori during their duty in Edo Castle, he couldn’t take it anymore, drew his sword, and attacked Yoshinaka. However, he was only able to wound Yoshinaka’s back and forehead before the guards separated them. Drawing one’s sword inside the shogun’s castle and attacking a superior was a grave offense. As a punishment, Naganori had to commit seppuku, ritual suicide, his castle and lands were all confiscated, and his retainers all became masterless ronin.

47 of Naganori’s most loyal retainers, under the leadership of Oishi Kuranosuke, swore an oath to avenge their master and kill Kira Yoshinaka, even though they knew that this was against the law. But Yoshinaka’s residence was well-guarded, and he expected Oishi’s men to attack him. So the 47 Ronin became monks and tradesman and pretended to live the life of normal commoners to make Yoshinaka believe that they were no threat. It is said that Oishi even went so far as to move to Kyoto, where he frequently visited the city’s red-light districts and got drunk almost every night. He sacrificed his whole reputation and honor as a samurai to clear himself of even the least suspicion that he could still be after avenging his lord. After almost two years, Yoshinaka finally let down his guard. On the night of December 14th, 1702, Oishi and his men attacked Yoshinaka’s mansion in Edo. They found Yoshinaka, killed him, and placed his head before their lord’s tomb to report the success of their revenge.

The shogunate officials were in a quandary because the hearts of the people belonged to the 47 Ronin, and they had lived up to the samurai ideals by being loyal to their lord even after his death. But they broke the law and had to be punished. As a result, they were ordered to commit seppuku, as it was considered more honorable to take their own life instead of being executed. On the 4th of February, 1703, all of the ronin committed ritual suicide, except for one who had run off immediately after they started their attack.

Traces of the 47 Ronin in Ako

I have known the story of the 47 Ronin for a long time, so I was quite excited to have the chance to visit some of the places connected to them in Ako. Although the Seto Inland Sea is known for many sunny days year-round, I somehow managed to visit on one of the few rainy days. But in no way did this take away from my excitement.

Ako Castle

I first went to the remains of Ako Castle in the center of the city. The castle was built in the mid-17th century upon the order of Asano Naganao, Naganori’s grandfather. It took 13 years to complete the construction. Even though the 17th century was a time of relative peace under the strict rule of the Tokugawa, the castle was designed with its defensibility in mind by two knowledgeable military strategists. The way inside the castle is not a straight line, but circles around the concentrically arranged walls and through a number of gates facing in different directions. The goal was to make it as difficult as possible for an attacker to make their way in and give the defenders more time to attack them with guns and arrows through shooting slits in the walls.

The castle’s location, with the Chikusagawa River to the east and the Seto Inland Sea to the south, made it even easier to defend. The castle was destroyed after the samurai rule ended in the 19th century, but parts of it have been restored, and the castle has been designated as a national historic site in 1971. Most of the inner areas have been transformed into a public park with beautiful gardens.

Oishi Shrine

Located on the grounds of Ako Castle is also Oishi Shrine (大石神社), which is dedicated to the 47 Ronin and their leader Oishi Kuranosuke. People come here to pay respect to their heroic deeds and to pray for being granted at least some of their determination so that they can realize their own personal ambitions. Many school children write their wishes on votive plaques and offer them to the shrine in the hopes of passing their next examination.

Oishi Shrine on a sunny day | Photo by Oishi Shrine

Ako City Museum of History

The Ako City Museum of History is located to the north-east of the castle’s remains. The buildings are designed in the style of old Japanese warehouses. Inside, you will find permanent exhibitions about the development of Ako Castle and its castle town, the story of the 47 Ronin, the long history of salt production in Ako, and about the old waterworks of the city. Most information is in Japanese, but an English pamphlet is available.

A Japanese Ryokan in the Heart of Ako

I stayed the night at Kariya Ryokan Q, located in the middle of Ako, not far from the castle remains. The building of the Japanese-style inn was first built in the Meiji period (1868-1912) but was recently renovated, recognizable by the pleasant smell of fresh wood. Despite the modern amenities, such as western-style beds and a bathtub that fills at the simple press of a button, you can feel the building’s history everywhere. If you are a taller person, as I am, you need to watch your head. Old Japanese houses were not exactly built with modern Westerners in mind. I can’t count how often I have hit my head since I came to Japan. On the positive side, the low-hanging wooden beams contribute to this kind of buildings’ rustic atmosphere and charm.

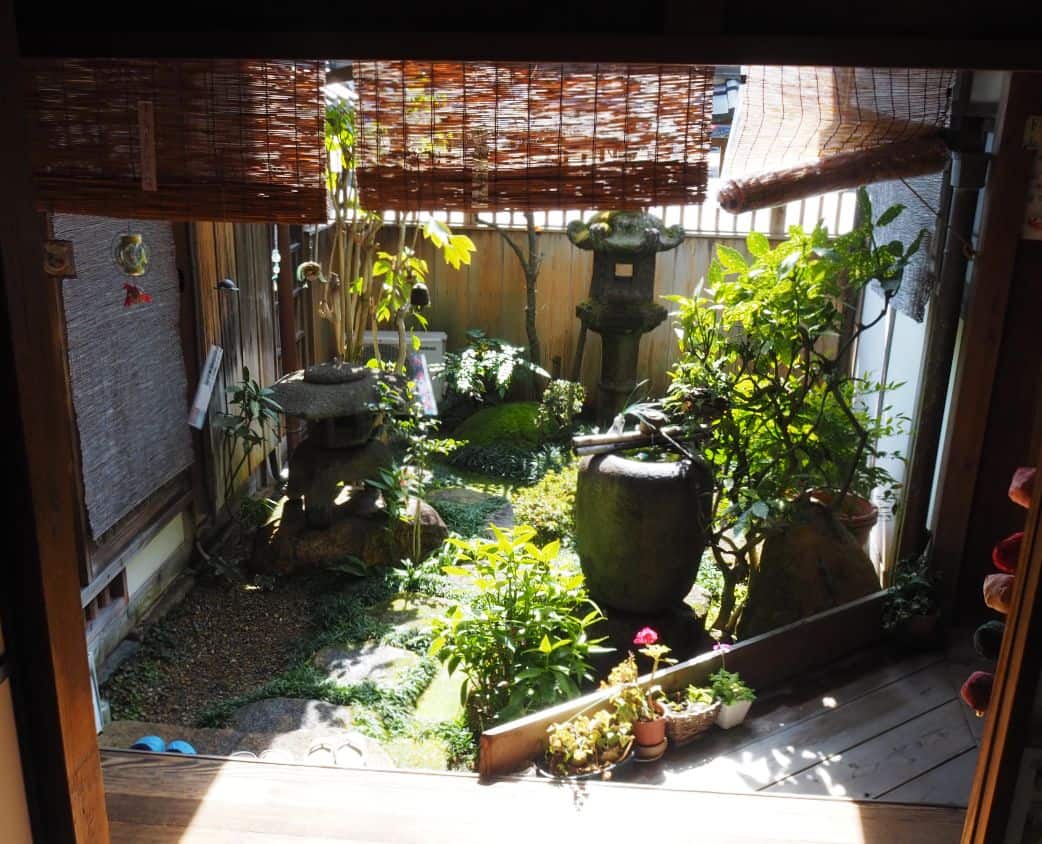

The cozy lobby on the first floor has a small enclosed Japanese garden and is a nice place to spend some time and relax, read a good book, or just hang around for a bit.

The Preserved Buildings of Sakoshi

Sakoshi (坂越) is only one stop away from Banshu Ako Station and not only a great place for hiking, but also for admiring traditional Japanese architecture. The Machinami (街並み) area of Sakoshi is just a short bike ride away from Sakoshi Station. Most of the old buildings of this area were built in the 19th century. Some of them are private residences, but there are also cafes, shops, museums. Even the local fire department is housed in one of the old buildings. I visited the Sakoshi Machinamikan, which used to be a bank, but now functions as a tourism information center and as a small museum. As soon as I entered, an elderly lady greeted me and started to tell me about the history of this building and the town. It was obvious how enthusiastic she was about sharing her knowledge of the area.

Okuto Sake Brewery

The building next to the Machinamikan is the Okuto Sake Brewery (奥藤酒造). This brewery was founded in 1601 and still produces Japanese rice wine. On the backside of the long building is a small shop where you can buy the sake directly from the producer. If you come here by bicycle, as I did, you might want to buy a bottle to drink later at your hotel or a smaller one to bring it back home as a souvenir.

Traditional Japanese Architecture Up-Close in Kyu Sakoshiura Kaisho

The Kyu Sakoshiura Kaisho is a building located at the end of Machinami street, close to the port. It was built in the 1830s and functioned as a meeting place for law enforcement and administrative work. You can go inside to see the traditional architecture up close. The building didn’t look very big from the outside, so I was surprised to see how many rooms were inside this house. The small Japanese garden shows how the designers managed to use every available space.

Oyster’s Paradise in a Traditional Japanese Meal

Not too far away from Machinami, located directly at Sakoshi Port, is Kuidoraku, a lively restaurant specializing in oysters. While many places serve oysters only in winter, at Kuidoraku, you can enjoy them all year round. The popular Pacific oyster in winter and the larger Iwagaki oyster in summer. You can grill the oysters directly at your table or order some of the various oyster dishes on the menu. If you would like to try many different oyster variations, you should try the Sakoshi Gozen that comes with deep-fried oysters, oysters marinated in vinegar, oysters in a miso hot pot, oysters steamed in their shell, and oysters in egg custard, together with sashimi, miso soup, pickled vegetables and a bowl of rice.

The oysters are landed right next to the restaurant where they are also sold directly.

A heron tries to get his share.

The Traditional Methods of Salt Production in Ako

Since ancient times, salt holds a special place in Japanese culture. It is believed to have purifying powers. If you have ever seen a sumo fight, you might have noticed that the wrestlers throw salt into the ring before the match starts to disperse bad influences. Salt is also one of the common offerings for Shinto gods at house shrines that some people have in their homes. Since Japan has no salt lakes or significant rock salt deposits, the Japanese had to rely on salt production from seawater. Because Ako is blessed with many sunny days, it has a long history of salt production.

In the 17th century, large-scale salt farms were developed under the rule of the Asano family. Even today, Ako’s salt accounts for 20 percent of the nationwide salt production. It is no surprise that shio ramen, a variety of the popular noodle dish that is based on a salty broth, is very popular in Ako. Compared to miso or pork bone-based ramen, it is lighter and has a more delicate taste. A good place to try shio ramen is the Ako Ramen Menbo, a ramen restaurant with a long history. The main shop can be found close to Banshu Ako Station

I visited the Country of Salt (Shio no Kuni), an open-air museum located in the huge Ako Seaside Park. If you travel with young children, this park with its small amusement area, obstacle courses, and vast playgrounds is a great place to spend some time.

At the Country of Salt, you can learn about the traditional methods of salt production in Ako. However, most of the information is in Japanese, so you might want to bring someone who can understand the language to get the most out of your visit. At the Marine Science Museum entrance right next to the Country of Salt, you can make a reservation for a salt-making experience where you produce your own salt and take it home with you.

During the experience, an expert in salt production explained how salt is produced from seawater. Because the salt concentration of seawater is only 3 percent, if you boil one liter of seawater, you only get 30 grams of salt out of it. Therefore, sunlight is first used to evaporate the seawater to make concentrated saltwater. This concentrated saltwater is what we used to make our own salt. Every participant had a gas cooker on their table with a pot filled with saltwater. The expert showed us every step, so it was easy to follow. First, we used a small wooden paddle to stir the boiling saltwater. This process is essential because the water evaporates faster, and the faster the water evaporates, the smaller the grains of salt become. After it boiled down a little bit, we used two paddles at the same time to stir the water until we had only lumps of salt left in our pots. We then used spoons to crush the remaining lumps until we had wonderful fine salt.

How to get to Ako

Ako City is easy to reach from Himeji Station (姫路駅), one of the main stops of the Tokaido Sanyo Shinkansen. From Himeji Station, it takes about 30 minutes and costs 590 yen by Sanyo Main Line to Banshu Ako Station (播州赤穂駅), the last stop of this train.

How to Get to Kariya Ryokan Q

Take the Sanyo Shinkansen from Shin-Osaka Station to Aioi Station (about 56 minutes), then catch the JR Ako Line from Aioi Station to Banshu Ako Station (about 13 minutes). By car, it takes approximately 25 minutes from Sanyo Shinkansen Aioi Station or 4 minutes from Banshu-Ako Station on the JR Ako Line. On foot, it takes about 8 minutes from Banshu-Ako Station on the JR Ako Line.

Ako might not have to offer such famous sightseeing spots as better-known tourist destinations such as Kyoto. Still, it has a very interesting and unique history that the locals are very proud of and happy to share with every visitor that comes to their pretty town. If you are a fan of samurai stories, you always wondered how to make salt from seawater, or you just want to stopover at an off-the-beaten-track destination that is conveniently located between Osaka and Hiroshima, you should definitely consider coming to Ako.

Sponsored by Ako City

No Comments yet!