Did you know that Japan is about to roll out a new set of banknotes very soon? This will be the first major redesign in 20 years, aiming to enhance security with the best of cutting-edge security features. At the same time, the new banknotes will be honoring three historical figures who have significantly shaped Japan’s socio-cultural and scientific landscape. These celebrated individuals are the “father of Japanese capitalism” Eiichi Shibusawa, the pioneering educator Umeko Tsuda, and the renowned bacteriologist Shibasaburo Kitasato.

This article will focus on the new banknotes to be issued in July 2024. For a general overview of Japanese currency, check out our Guide to Japanese Yen.

Japan’s New Banknotes: What You Need to Know

The new banknotes will go into circulation from July 3, 2024. This is what the new designs will look like:

- 10,000 Yen Note: Featuring Eiichi Shibusawa, a key figure in Japan’s economic modernization. The reverse side showcases Tokyo Station’s Marunouchi Building.

- 5,000 Yen Note: Depicts Umeko Tsuda, a pioneer in women’s education, with the back featuring wisteria flowers.

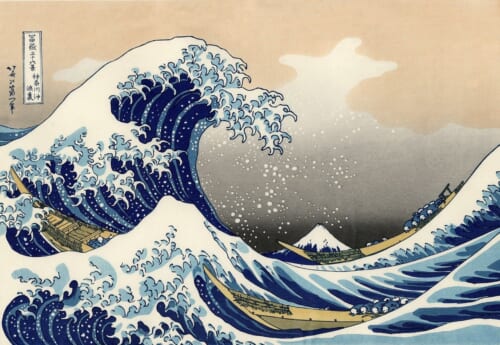

- 1,000 Yen Note: Highlights Shibasaburo Kitasato, a pioneer in bacteriology, with the reverse side showing The Great Wave off Kanagawa, one of the most iconic ukiyo-e prints from Katsushika Hokusai.

As for the security measures, the Bank of Japan went all out to give counterfeiters a hard time with the new designs. Among their standout features:

- Holograms: Color-changing holograms visible when the notes are tilted. In a world first, some of those holograms also feature a smaller version of the aforementioned historical figures, with a 3D effect making it look like rotated portraits!

- Watermarks: New high-definition watermarks with intricate designs and latent images that appear when tilted or held up to the light.

- Microprinting: Tiny text difficult to replicate accurately.

- Tactile marks: Special patterns made with intaglio printing techniques to achieve a special texture that helps to make it easier for visually impaired people to identify each banknote.

- Special luminescent ink: Special prints only visible under ultraviolet light.

After the new banknotes are issued, existing banknotes will remain valid so you don’t need to worry about the need to exchange your money. This applies to banknotes issued before the ones currently in circulation as well. In fact, many businesses are biding their time to invest in new expensive cash machines (like those used in ramen joints, for example) as the current ones are only configured for existing banknotes and cannot be modified. Similarly, not all vending machines can be updated overnight so it will probably take a while before you can use the new banknotes in all of them.

For further details, you can check the Bank of Japan’s dedicated website.

Why Are These New Banknotes Introduced?

Since 1984, Japan has adopted a cycle of about 20 years for new banknotes. One of the primary reasons for regularly updating banknotes is to incorporate the latest security features. Technology advances mean that new counterfeiting methods are constantly emerging, and updating banknotes’ design and security features helps to stay ahead of counterfeiters. The new advanced features previously mentioned are significantly more difficult to replicate. For now at least.

Honoring a New Set of Historical Figures

During the last few decades, the banknote designs have highlighted the memory of historical figures that have had an everlasting impact in modern Japan for several reasons, so the new set continues along the same theme.

Eiichi Shibusawa: The Architect of Modern Japanese Capitalism

Eiichi Shibusawa’s selection for the new 10,000 yen note, honors his monumental contributions to Japan’s economic development and his attempts to improve the social standing of lower classes, making him a fitting symbol for modern Japanese currency.

He was born into a wealthy farming family on March 16, 1840, in Chiaraijima Village, Saitama Prefecture, and is widely regarded as the “father of Japanese capitalism.” His early exposure to Confucian ethics shaped many of his later visions applied to business and a will for much-needed social reform. He eventually served under Yoshinobu Tokugawa (who would be the last shogun and although ultimately unsuccessful, shared similar reformation ideals), who granted him Samurai status. And despite being initially hostile to any foreign influence, Shibusawa’s perspective shifted dramatically after his 1867 visit to the Paris International Exposition, where he was impressed by Western economic practices.

Upon returning to Japan, after the Shogunate was no more, Shibusawa played a crucial role in the Meiji government’s modernization efforts. He served in several key positions, including Chief of the Tax Bureau and head of the Currency Office, where he laid the foundation for Japan’s financial and corporate infrastructure. His transition to the private sector in 1873 marked the beginning of a prolific business career. He established and supported around 500 enterprises, including the First National Bank of Japan, which played a pivotal role in mobilizing private capital for industrial development.

Shibusawa’s business philosophy was reportedly deeply rooted in ethical principles, advocating the integration of morality and economics. He believed business should serve society, a principle reflected in his extensive philanthropic efforts, including founding educational and social welfare institutions, like the Japan Red Cross.

Umeko Tsuda: The Champion of Women’s Education in Japan

Umeko Tsuda‘s selection for the new 5,000 yen note pays tribute to her great contributions to women’s education and social expectations. Her legacy as a visionary educator who championed equal opportunities for women makes her a fitting symbol for modern Japanese currency.

Born on December 31, 1864, in Tokyo, she was a pioneering figure in women’s education in Japan. At just six years old, she was sent to the United States as part of the Iwakura Mission, making her one of the first Japanese women to study abroad. Her early education in Washington, D.C., where she lived with Charles Lanman, profoundly influenced her future ambitions. Tsuda excelled academically, mastering English and other subjects, and developed a strong belief in the importance of education for women.

After returning to Japan in 1882, Tsuda faced cultural challenges and societal expectations that limited women’s roles. Dissatisfied with the educational opportunities available to women, she returned to the US to study at Bryn Mawr College, where she majored in biology and education, strengthening her resolve to transform women’s education in Japan.

In 1900, Tsuda founded Joshi Eigaku Juku, later known as Tsuda University, to provide women with high-quality liberal arts education. Despite initial financial struggles and societal resistance, her efforts paid off leading to the institution’s growth and further recognition. Her commitment to education extended beyond her school; she was also the first president of the Japanese branch of the YWCA and a fervent advocate for women’s social reform.

Shibasaburo Kitasato: The Pioneer of Modern Bacteriology

The selection of Shibasaburo Kitasato for the new 1,000 yen note celebrates his tremendous influence in medicine and public health. Hailed as the “father of modern Japanese medicine,” his legacy goes beyond his scientific achievements, including his commitment to advancing medical research and education.

Born on January 29, 1853, in Kumamoto, Japan, he went on to become a significant figure in the field of bacteriology. After studying medicine in Tokyo, Kitasato went to Germany in 1885 to work under the eminent bacteriologist Robert Koch. There, he made groundbreaking contributions, including the first pure culture of the tetanus bacillus, paving the way for antitoxin development.

After his return to Japan in 1892, he founded the Institute for Infectious Diseases, Japan’s first private research center dedicated to studying infectious diseases. In 1894, during an outbreak of the bubonic plague in Hong Kong, Kitasato independently discovered the plague-causing bacterium, Yersinia pestis, alongside Alexandre Yersin. This discovery was pivotal in advancing the understanding and treatment of the plague.

Kitasato’s work was also instrumental in establishing multiple medical institutions, including the Kitasato Institute and the medical faculty at Keio University. His contributions to public health were recognized internationally, and he was honored with numerous awards and titles, including ennoblement as a baron in 1924.

As you can see, the new security update for the banknotes isn’t just valuable for its practical benefits (although admittedly, small businesses are less than thrilled about the hassle), it’s also a good opportunity to look back and celebrate the legacy of historical figures that have played key roles shaping the Japan that we know today. Or, at the very least, it gives numismatists a novelty to look forward to.

No Comments yet!