Tsunami (津波). Literally, wave (波) in the harbour (津). The fact this Japanese word is the universal term used nowadays to describe when the sea fury decides to sweep away everything in its path gives us an idea of how this frequent and widespread phenomenon has influenced Japan. Images of the greatest tragedy in the country’s recent history are still fresh in the collective memory, one decade later. Safety measures up to that point became insufficient when natural forces showed everyone the price of overconfidence.

How Common are Tsunamis in Japan?

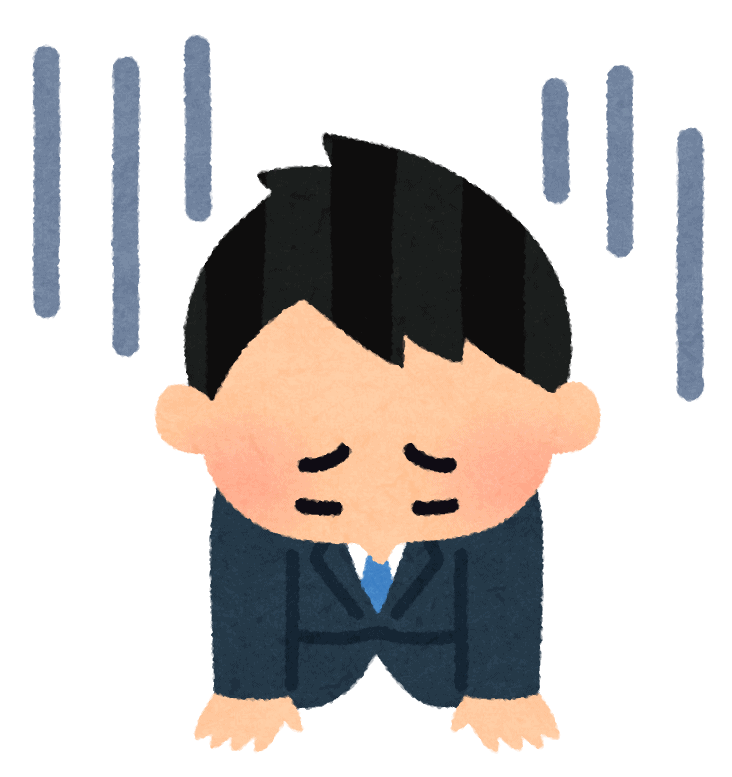

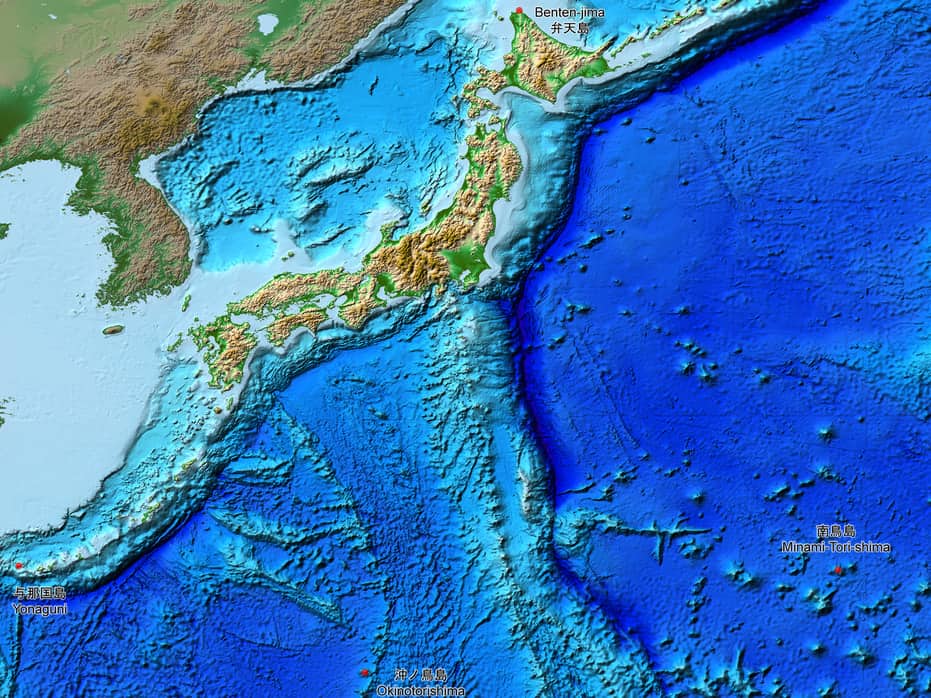

Japan is a country where earthquakes are the order of the day due to its position on the edges of several tectonic plates whose boundaries match the entire Japanese archipelago. The constant collision of these plates generates high seismic activity in this area, which results in a very frequent number of tsunamis every few years.

How Do Tsunamis Occur?

As we have already indicated, the vast majority of tsunamis originate from earthquakes, as it’s been the case for approximately 80% of recorded tsunamis since the beginning of the 20th century. However, they could also be generated by landslides, volcanic activity, certain atmospheric phenomena (called a ‘meteotsunami‘) or even the passage of an asteroid or comet that grazes too close to the sea.

What to Do in Case of a Tsunami in Japan?

First of all, as soon as tremor is felt, no matter how slight it may seem, the best thing to do is to consult local media, as they usually provide a quick update whether there is a tsunami warning after an earthquake or not. For those accustomed to using social media, Twitter is also tremendously useful for instant information. For example, the official Japan Weather Association account immediately confirms where the epicentre is, the intensity, and whether a tsunami is expected or not. If there’s a tsunami risk or warning, the same association has a handy guide of the steps to follow:

- Seek the highest possible location. After a tsunami warning, prioritize moving to the highest areas. Sometimes the height of the waves may exceed the predictions, and even some places designated as shelters may be vulnerable.

- Avoid the use of private vehicles. One might think that the safest thing to do is to get away quickly from the risk zone in a car, but in reality, this is counterproductive. There is a real possibility of getting caught in a traffic jam and ending up engulfed in a wave.

- Stay away from rivers. The danger is not only limited to coastal areas, but rivers are also at risk of experiencing strong floods. It is also advisable to stay away from them, especially if you are near a fast-flowing river.

- Once in the evacuation area, stay there. The risk isn’t over after the first wave. Sometimes there are several waves within minutes or even hours, and can be higher than the first waves. Once you reach the evacuation zone, it is best to stay there and not leave until the tsunami warning has ended.

What Regions Are Most at Risk of Tsunamis?

To date, there’s no official database classifying the risk level of each zone throughout the country despite legislative efforts made after the 2011 earthquake. What’s available for now is a report published in January 2020 where the government focuses on the Nankai Trough area, as a high magnitude earthquake is likely because of its geological features.

Recently, the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology published this interview with seismologists Yusaku Ota and Narumi Takahashi, explaining the research conducted since the 2011 earthquake and the efforts being made to improve predictive capabilities.

Ota and his team have begun building a comprehensive Earth crustal motion monitoring system, called REGARD, in collaboration with the Japan Geospatial Information Authority. This system analyzes data from GEONET (GPS-based observation network) in real-time to predict how far a tsunami may reach beyond the coastline. It’s worth noting that this GPS research for tsunami prediction has been developed and implemented just six years after the Tohoku earthquake in what has been an exceptionally rapid process.

What are Japan’s Largest Tsunamis in History and What Damage Did They Cause?

Before the existence of modern measurement tools, assessing the various tsunamis and earthquakes throughout history is a relatively complicated matter. For example, to categorize earthquakes that occurred before 1890, experts rely on multiple sources to compare the physical affects on land and human (on the record information) and make estimates based on comparisons with recent disasters. Due to the nature of this type of information, data for older earthquakes may vary depending on the source. Therefore it’s necessary to consider that figures indicated for the magnitude of such events are approximate estimates.

According to the world-historical record in the database of the American agency NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), these are the five worst tsunamis that have occurred in the history of Japan:

- June 15, 1896: The Sanriku coast tsunami, corresponding to the area of Iwate Prefecture. The most devastating in history in terms of the number of deaths, estimated at around 27,000, with more than 9,000 injured and 11,000 houses destroyed. It occurred after a strong earthquake of magnitude 8.3 and produced waves up to 38.2 meters high.

- March 11, 2011: The largest tsunami in recent history, which completely shook the coast of the Tohoku region and generated the largest nuclear crisis in history after Chernobyl. It followed the strongest earthquake ever recorded in Japan, with a magnitude of 9.1. The height of the waves almost quadrupled the estimates at the time, reaching 39.2 meters in height. More than 18,000 people lost their lives, in addition to injuring more than 6,000 people and destroying more than 120,000 buildings.

- May 21, 1792: The Shimabara coast tsunami, Nagasaki Prefecture. After a season of volcanic activity on Mount Unzen, a series of tremors caused large landslides in the Ariake Sea, generating waves that on at least one occasion exceeded 55 meters. The disaster resulted in 15,000 deaths, more than 700 injured and the destruction of 6200 properties.

- April 24, 1771: The Great Yaeyama tsunami in what’s now part of Okinawa Prefecture. An earthquake in the Yaeyama Islands of magnitude 7.4 generated waves that reached 85 meters high, taking more than 13,000 lives and about 3,200 houses in the archipelago.

- December 30, 1703: the Genroku earthquake tsunami on the southeast coast of the Kanto region. Following an earthquake of magnitude 8.2, the coasts of Kanagawa and Shizuoka prefectures suffered waves of more than 11 meters, resulting in more than 5,000 deaths and the loss of more than 20,000 buildings.

Fortunately, this history of natural disasters has also meant that Japanese society has learned and adapted to improve its safety regulations and protocols at every step of the way. As a result, over the last two decades, more than 30 tsunamis (and countless earthquakes of medium or low intensity) have been recorded along the Japanese coastline without human losses, apart from the tragedy of 2011.

Featured image: The Great Wave by Hokusai from Wikimedia Commons