Ten years after a monstrous tsunami devastated the Pacific coast of Tohoku (東北) on March 11, 2011, it’s still a deeply moving experience to travel through the region in its traces.

Provoked by the undersea magnitude-9.1 Great East Japan Earthquake (東日本大震災) far out in the ocean, the massive tsunami crashed over 500 kilometers of coastland across three prefectures. By now, we have all seen images of the terrifyingly powerful black wave pummeling ashore, swallowing everything in its path. Survivors speak of the overwhelming stench, the crumpling of houses and the crunching of debris, the roar of the earth, or the groan of the sea. Its aftermath has been compared to the hellish landscape of annihilation following the explosion of a nuclear bomb. Experiencing a real-life tsunami is so surreal that the rest of us can only try to imagine what it was like and piece together a fragmented impression from what now remains.

The 2011 Japanese earthquake and tsunami killed over 20,000 people and displaced tens of thousands more. But despite the underlying trauma in this collectively scarred region, many Tohoku residents in the most severely hit areas have cultivated resilience to rebuild and revive their communities and even welcome visitors. At the same time, they have preserved artifacts, refurbished buildings into memorials, and documented as much as possible in order to tell stories of the disaster and recovery to future generations.

So many of these initiatives now exist that they have been connected through a grassroots network called “3.11 Densho Road” (3.11伝承ロード). It’s a sort of pilgrimage route with the mission of passing on memories, testimonies and lessons learned, stretching from Iwaki in Fukushima (福島) prefecture to Hachinohe in the north of Tohoku, although most of the sites are concentrated along the Sanriku Coast (三陸海岸) in Miyagi (宮城) and Iwate (岩手) prefectures. The memorials range from ruins and stone markers to dedicated exhibitions, museums, and parks. 3.11 Densho Road’s mission statement: “Lessons save lives.”

Beyond Sendai’s Coastal Bike Paths, a Skeleton School

To tell the truth, I had no idea that such a pilgrimage route even existed when I first traveled to Tohoku. I had arrived in Sendai (仙台) to visit a friend who was working there temporarily as part of a touring show, and everything about this port city seemed perfectly functional and modern.

It wasn’t until I hopped on my bicycle and headed out to the coast for a scenic ride by the seaside that I came face-to-face with the shock of Sendai’s unseen reality: clusters of loudspeakers overlooking stark farmlands, 11-meter-high evacuation mounds, freshly cemented roads littered with orange cones and cranes, infinity seawalls, stretching out to the horizon in either direction. Almost a decade after the annihilating tsunami of 2011, this modern city’s coastal area still screamed: “Under Reconstruction.”

Further out, newly paved, totally deserted bike paths lined the Meiji-period Teizan Canal (貞山運河) surrounded by dry grasses and wild trees inhabited by large birds. The atmosphere was both peaceful and eerily apocalyptic. After riding along these paths for several kilometers without meeting another human being, I stumbled upon a sign pointing inland toward a school.

The skeleton of Sendai Arahama Elementary School (仙台市立荒浜小学校), founded in 1873, stands alone in a wasteland less than a kilometer from the shore. On March 11, 2011, the school served as an evacuation site and lifebuoy for 320 people—students, staff, and neighborhood residents—as the thick black wave surged around the building up to the second floor. They were trapped there for 27 hours.

The gutted school has since been preserved as a memorial, whose twisted balcony railings, damaged ceilings, and bent walls bear witness to the overwhelming force of the tsunami. Inside, marks still show the highest level of the rising water, while rooms on the fourth-floor exhibit photos, documents, as well as blankets and food reserves used by the evacuees.

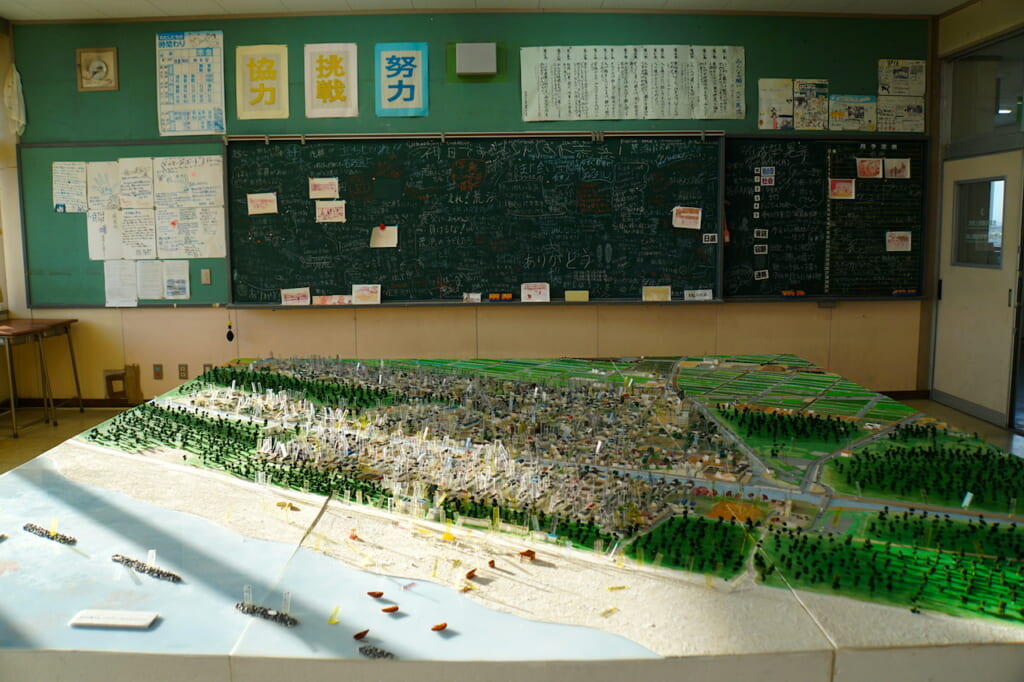

In one room, a memorial blackboard with chalked wishes from visitors faces a carefully scaled model of the town before the disaster, where each house is marked with a family name. I watched in silence as two older women located their houses in the recreated neighborhood, then pointed out on the maquette where someone they knew had been at the time the tsunami hit.

Another room exhibits the analog gymnasium clock, which stopped ticking underwater at precisely 15:55 on March 11, 2011. Projected behind it, a riveting 17-minute documentary film recounts the 27 hours that followed the 14:46 earthquake, up until the final helicopter rescue of the last evacuees.

The film left me with two indelible moments: sweeping aerial images of tiny humans stranded on the school’s rooftop, completely surrounded by a belligerent black sea; and the school principal recalling how less than a year ago, following the 2010 earthquake and tsunami in Chile, the school’s designated evacuation site had been relocated from the gym to the rooftop, and blankets transferred to the third floor (“If we had evacuated to the gym, we would all be dead now”).

As I thanked one of the staff on my way out, she asked me where I was visiting from. When I replied that I had traveled from Tokyo, she momentarily disappeared, then re-emerged to hand me a B5-size pamphlet that opened up into a 4-page map of the coastal Tohoku region. It was titled “3.11 Densho Road”.

I was not in Japan in 2011. What I had learned of the disaster at that time had been relayed by international media, which had increasingly shifted their focus from the tsunami deaths and destruction to the nuclear meltdowns, mass evacuations, lingering radiation, Safecast project, and environmental pollution reminiscent of Chernobyl. For many people outside Japan, the entire 2011 Japanese earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear tragedy had been spectacularly packaged and similarly reduced to a single word: Fukushima.

But what had become of the rest of Tohoku? Over the past ten years, I had mistakenly assumed that this coastal region north of Fukushima prefecture must have slowly but surely recovered and rebuilt. Obviously, this was not the case everywhere. I decided to head north up the coast.

Ishinomaki 2.0, the Most Interesting Town in the World

The hypocenter of the 3.11 megathrust earthquake was located 24 km under the sea, about 130 km southeast of the Oshika Peninsula in Ishinomaki (石巻). This city with a total population of 160,000 in early 2011 suffered the most damage and the most deaths from the tsunami, where entire districts were inundated, and nearly 4,000 people perished.

The south bank of the Kitakami River is still haunted by the memorial ruins of Okawa Elementary School (石巻市立大川小学校), the only school in Japan where—due to unfortunate lack of foresight, poor leadership, and conflicting opinions between the time of the earthquake and the surge of the tsunami—74 out of 78 children drowned.

Bronze hand of local manga artist Ishinomori Shotaro

From Ishinomaki train station, an hour away from Sendai, I unfolded my bicycle and rode leisurely through the modest city center. On a weekday afternoon, a few shops and restaurants were open but not busy, commercial streets were uncrowded, and residential neighborhoods were peacefully quiet. I headed toward the old Kyukitakami River, where I began to hear the sounds of construction sites, and finally rang the doorbell at Kikuchi Ryokan (菊地旅館).

Although I had no reservation, the owner immediately welcomed me and my bicycle with a warm smile and showed me to a modern tatami room, complete with the wooden bed frame and en-suite bathroom. The few other guests in the ryokan were all construction workers. Breakfast was included, said my host, but they wouldn’t be able to prepare dinner for me that same evening.

No problem, I replied, happy to put down my backpack and set out again on foot to explore the local neighborhood. But by that time, it was after dusk, and night had clearly fallen on Ishinomaki. On the main street, only one very contemporary looking storefront still had its lights on behind a welcoming sign that read “IRORI+Cafe”.

Inside, I went up to the coffee bar and asked if they served food.

“I can make you a pasta,” said the barista. “Have a seat.”

I took a seat and let my eyes peruse the room. It appeared to be a hybrid space, somewhere between shop, gallery, and office, exhibiting or selling various handcrafted items, graphic designs, books, and collectibles, with amenities for sewing, meeting, and coworking in the back. On the wall across from the bar area was a hand-drawn map of Ishinomaki’s commercial district on a piece of wood, marked with the names of individual businesses. A hanging black T-shirt displayed big white block kanji: “世界で一番面白い街を作ろう ISHINOMAKI.JAPAN” (“Let’s create the most interesting town in the world”). Another T-shirt bearing a lightning-inspired kanji logo simply read “Ishinomaki 2.0”.

“What is Ishinomaki 2.0?” I asked.

The young barista explained that Ishinomaki 2.0 was an initiative by native Matsumura Gota to revive the town, which was still struggling to recover from the 2011 disaster. He himself recalled the overwhelming destruction left behind by the tsunami, describing a boat that had crashed through a building. All the objects in this space, he said, were created by local residents. Members could also meet here to plan projects and co-work. He apologized for the map on the wall not being up to date with more recently opened shops.

Ishinomaki 2.0 fosters creative community projects, especially led by young people. IRORI (Interaction Room Of Revitalization and Innovation, or “hearth” in Japanese) is the name of its multi-purpose cultural space, renovated from a damaged garage into a shared office space in December 2011 and refurbished into its current incarnation with a public cafe area in 2016. The DIY wooden furniture is signed Ishinomaki Laboratory (石巻工房), one of several creative revival projects that emerged from the aftermath of 3.11. Another is the Reborn-Art Festival, which also features permanent art installations around the greater Ishinomaki area, and whose next editions will be held in late summer 2021 and spring 2022.

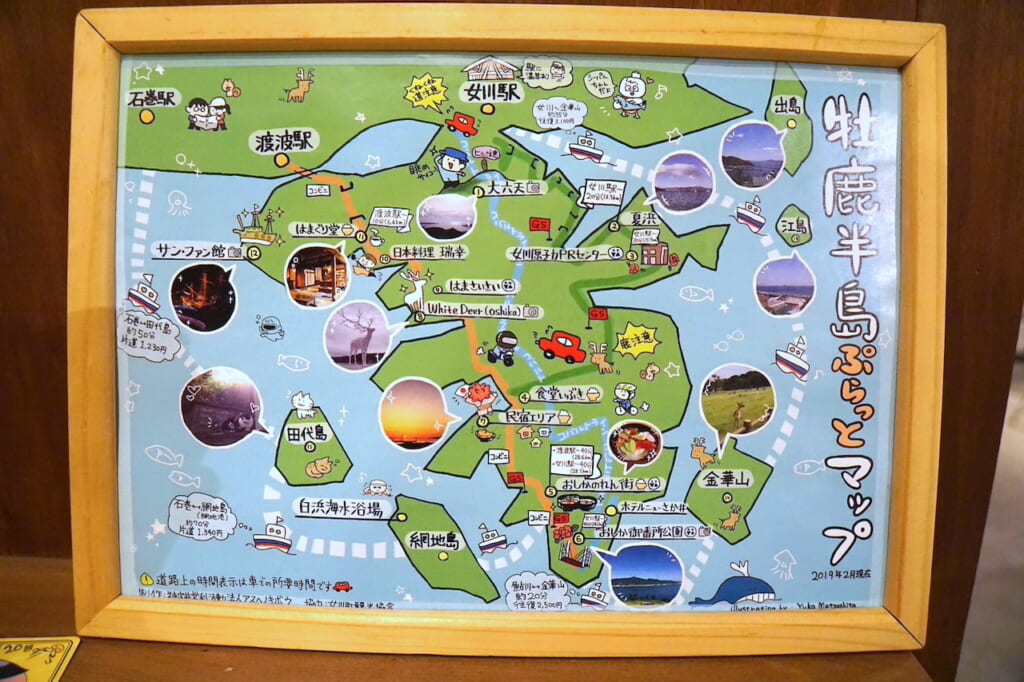

Before leaving, I walked around the space to take a closer look at some of the Made-in-Ishinomaki objects on display. By the window stood an almost life-sized deer figure made of twisted driftwood from Oshika, sculpted by a young artist named Tomatsu Atsushi. Framed on a shelf, another hand-drawn map caught my eye. It was a topological illustration by Matsushita Yuka dated February 2019, spotlighting various sightseeing attractions around the Oshika Peninsula (牡鹿半島): Tashirojima (田代島) cat island, Kinkasan (金華山) sacred deer island, the giant White Deer sculpture in Oginohama (荻浜), observation points and photo spots, ferry connections between the islands, Route 2 going down the peninsula from Watanoha station, and the scenic “Cobalt Line” mountain road leading back up to the seaside port town of Onagawa.

The Ride to Onagawa, Reborn at the End of the Line

The next morning, I hopped back on my bicycle and headed east toward the peninsula. I rode around construction sites and across the river, past the city’s iconic Ishinomori Mangattan Museum (石ノ森萬画館), a large white-domed “spaceship” built on the central islet to house the bold cartoon artwork and retro action figures of the local manga artist Ishinomori Shotaro (1938-1998), whose colorful characters still populate downtown Ishinomaki. In 2011, the first floor of the museum was completely destroyed by a 6.5-meter-high wave.

I continued eastward, past designated tsunami evacuation buildings in residential neighborhoods and bleak office buildings with blue signs indicating the highest level of the 3.11 tsunami flood water, often above the second floor. In the industrial district of Watanoha (渡波), large kanji printed on the side of a fisheries warehouse cheered “がんばろう石巻!!” (“Let’s go, Ishinomaki!!”).

Past the landmark Ishinomaki Fish Market (石巻魚市場)—razed in 2011, rebuilt and reopened in 2015—an empty swimming beach was surrounded by a seawall, topped by a stairway dike, buffered by a plaza, and just 140 meters away from a dedicated tsunami evacuation tower.

Closer to Watanoha train station, I stopped by the Nozomi house, where a diligent team of local women transforms broken dishware and shards of ceramic debris left over from the tsunami into beautiful pieces of jewelry. (But that’s another story.)

I followed the Ishinomaki railway line along narrow winding Route 398 contouring the Mangokuura (万石浦) inland sea, up into white cemented residential neighborhoods still under construction on the hills, all the way to the end of the line on the Sanriku Coast: Onagawa (女川).

This small fishing town was literally decimated by the 2011 tsunami, when an 18-meter-high wave funneled into the rias of Onagawa Bay and swept 1 kilometer inland, inundating half of its 25 designated evacuation sites, razing its train station, drowning over 800 people (almost one-tenth of its population) and destroying 80% of its infrastructure.

But Onagawa is also an example of genuine rebirth, spurred by a visionary mayor (Suda Yoshiaki), local industry creatives, and solidary community members determined to readapt, renew and revive. Like many other towns in Japan, Onagawa’s population had already been rapidly decreasing over the past decades as young people moved away to the big cities. But unlike many other tsunami-ravaged towns that subsequently invested in higher sea walls, Onagawa opted to build an open shopping area just above its port to welcome visitors with a view of the bay.

The new symbol of reborn Onagawa is the JR train station, with its white roof inspired by the spread wings of a seagull, including a third-floor observation deck looking out over the town and the second-floor Onsen Yupo’po (温泉ゆぽっぽ). Opened in March 2015, the station was designed by Ban Shigeru, a Japanese architect renowned for his work in disaster-struck areas, who also upcycled thousands of shipping containers into temporary housing units in Onagawa just after the tsunami.

A few steps behind the station, Hotel El Faro (ホテル・エルファロ) is an entire guest accommodation complex assembled in 2017 with refurbished trailer homes painted in soothing pastel hues, owned and managed by an Onagawa native whose original family inn was destroyed in 2011.

But the reborn town’s main attraction is the red brick promenade that extends from the station down toward the ocean. Seapal Pier Onagawa (シーパルピア女川), built just above the industrial harbor and inaugurated in December 2015, is a commercial plaza where around 30 local artisans, restaurateurs, and other retailers now offer their goods and services. It’s a strikingly peaceful scene, in welcome contrast to the conspicuous construction sites of so many other coastal towns.

One of the founding members is Soap Workshop Kuriya (三陸石鹸工房 KURIYA, Sanriku Sekken Koubou Kuriya), which offers exquisite soaps made from local natural ingredients and essential oils, presented as aromatic elixirs condensed into dainty cubes, all handcrafted by Mr. Kuriya and his assistants (who also offer soap-making workshops for visitors). Another original novelty shop is Kanpo’s Factory, which sells toys made of laser-cut corrugated cardboard by local cardboard manufacturer Konno Konpou, featuring a life-sized model of a Lamborghini.

Many more of these post-tsunami initiatives are led and carried by local women working behind the scenes, who survived the tragedy by learning new skills and forging new paths to recovery.

Ceramika Factory (みなとまちセラミカ工房, Minatomachi Seramika Koubou), founded by Abe Narumi in 2012, immediately drew me into its storefront with myriad colorful Spanish tiles. Following the disaster, Onagawa began a cultural exchange with Galicia in Spain, whereby a dozen local women learned to craft traditional Spanish tiles. They have since honed their skills by making and baking thousands of tiles, including memorial tiles and custom nameplates for local businesses around the pier, and giving workshops.

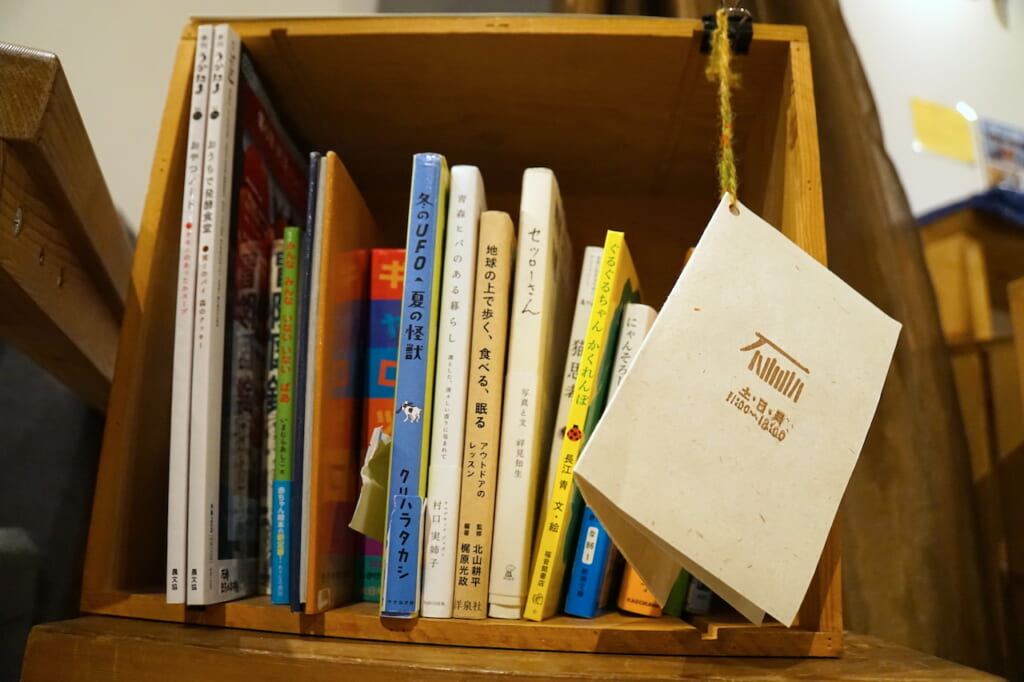

I finally bought a walnut/maple wood keychain from Onagawa Factory, a shop specialized in smooth fish-shaped charms made from various types of local woods. Meticulously handcrafted by local women who used to work in fish-processing factories before the tsunami, their signature long, slim sanma (saury) is a symbol of the town’s traditional fishing industry. The women have since expanded their offerings to include various laser-engraved accessories, cheesecake made with Oshika sea salt, and even collaborated with their neighbor Megumi (恵) to produce chopsticks wrapped in silk cases.

Onagawa, from Local Nuclear Refuge to Drying Barracuda

The Megumi Project is embodied by a small team of local women working out of trailers in Urashuku (浦宿), all of whom had lost their homes in the tsunami, who refocused their skills to sew and create stylish accessories out of second-hand vintage kimono fabrics. I had first heard of Megumi as the sister project of Nozomi in Ishinomaki, both supported by American missionaries. In Onagawa, Megumi is the core project of Kizuna Friends (絆フレンズ), founded by Lorna Gilbert and her husband, Andy. At Seapal Pier, their retail shop is managed by 38-year-old Onagawa native Naoe Miyuki.

When I came into the shop around midday, the promenade was relatively quiet, while a few visitors, mostly older people from around the region, wandered in to browse the bags, scarves, book covers, and other handcrafted items. In between welcoming customers and explaining the history of the Megumi Project, Miyuki mentioned that while her own family house on the hill was left relatively intact after the tsunami hit, she herself had been trapped for three days inside her former workplace… at the Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant.

Located further down the peninsula, the reactors were undamaged and had been immediately shut down, so the nuclear plant actually served as a local shelter for several hundred people, where they had emergency food, supplies, and a generator.

Outside, they were surrounded by muddy floodwater, floating bodies… “I have no words to describe it,” said Miyuki. It was like an image of hell. When the waters finally receded, she made the 40-kilometer trek back home, alternately walking and hitchhiking.

After the disaster, Miyuki spent a couple of years in Australia but returned to her hometown in 2015, as it had always been her plan to work in Onagawa after reconstruction. In addition to teaching English to locals and Japanese to foreigners, she has successfully taken the relay from Lorna in managing the Megumi Project since August 2019.

Naoe Miyuki

Together we walked down the promenade to the far end of Hama Terrace, where we each picked up a seafood rice bowl from Fish Market Okasei (お魚いちば おかせい) for lunch. On the patio, tantalizing rows of fresh-caught barracuda (カマス) were hanging out to dry in the sun—the quintessential image of Onagawa’s slowly recovering industry.

Making our way back through the hall, we stopped for samples and tea at Marukichi Onagawa Hamameshiya (マルキチ女川浜めし屋), which specializes in local hoya (sea squirt) and Marukichi’s signature product “Rias poetry” sanma kobumaki (リアスの詩 さんまこぶ巻), boiled local saury hand-rolled in kelp from the Karakuwa peninsula. Above the stand in Hama Terrace is proudly displayed the large wooden “Rias poetry” sign found under the rubble of the original storefront on Onagawa Port.

As I thanked the hosts for the delicious fresh seafood, the man was surprised to hear that I was staying at Kikuchi Ryokan in Ishinomaki.

“My house was in Minamihama,” he said. “You can see the area from the hill just behind the ryokan.” He brought over a city map of Ishinomaki and showed me exactly where it was on the map.

“Please, go up the hill and take a look,” he insisted. He marked the spot and circled the area so that I couldn’t miss it. I squinted at the empty white lines weaving around the harbor.

“What’s there now?” I asked.

“NOTHING!” he shot back, the raw surge of emotion in his voice driving the point home. Quick to oblige, I promised him I would go and have a look.

And the next morning, I did.

Hiyoriyama (日和山) is a symbolic hill in central Ishinomaki that directly overlooks the districts of Minamihama (南浜) and Kadonowaki (門脇) to the south, and the Kiukitakami river to the east, at the northernmost edge of Sendai Bay. By late spring, it is covered in cherry blossoms.

In March 2011, at 56 meters above sea level, Hiyoriyama provided a life-saving high ground from the massive tidal wave, where numerous people sought refuge and spent the night under the falling snow. On the plateau around a solemn stone torii, naturally framed, uncaptioned photo prints show selected views of the surrounding “before” landscape, juxtaposed with the actual views of ongoing construction sites on barren land.

I looked out across Minamihama, where the man’s house would have been, in a flat residential area neighboring the industrial warehouses and factories of Ishinomaki’s once-thriving port. It was here that the tsunami had razed some 3,000 homes, a hospital, and a cultural center, while fires burned whatever was left.

The entire area has since been declared a danger zone, where construction of any residential property is prohibited. Since my visit, Miyagi prefecture’s official Ishinomaki Minamihama Tsunami Memorial Park (石巻南浜津波復興祈念公園) opened its museum on June 6, 2021.

I decided to venture further up the Sanriku Coast, where Iwate prefecture’s own tsunami memorial park and museum were already open to the public.

Rikuzentakata, Remote Remnants of the City before the 2011 Tsunami

Ten years after the disaster, a dedicated BRT bus service still replaces the broken railway line on the severely damaged rias coast between Minamisanriku (南三陸) and Ofunato (大船渡). From Maeyachi train station (前谷地駅), I took a scenic bus ride through the mountains and along the coast to Kesennuma (気仙沼), then another bus to Rikuzentakata (陸前高田).

After finding no vacancy on a Saturday afternoon at three different accommodations, I finally cycled the last 10 kilometers around the bay, past more construction sites and damaged roads, until I arrived just as dusk was falling at Minshuku Musashi (民宿むさし)—which welcomed me with open arms, a hot bath, and a generous seafood dinner.

As the hostess gave me an introductory tour of the intimate guest house, she made sure I saw the location of each emergency exit in the annexed two-story building. When the tsunami hit Rikuzentakata with an 18-meter-high wave over Hirota Bay (広田湾) in 2011, this guest house on the hill had served as a community evacuation site. The host couple were proud of the house’s preserved traditional architecture and never took safety measures for granted.

In Iwate prefecture, the city of Rikuzentakata suffered by far the most casualties, with more than 1,750 people dead or missing and over 80% of its urban area submerged by the tsunami. The city used to be famous for its lush Takata Matsubara (高田松原), a dense evergreen forest of 70,000 pine trees planted 350 years ago on a long sandbank. Today, Rikuzentakata’s landmark symbol of resilience is the single (now preserved) 170-year-old Miracle Pine (奇跡の一本松, kiseki no ippon matsu) that survived the wave.

The next morning, I cycled back up the coastal Route 45 toward the central part of the bay, past signs marking the beginning and end of the section of land that had been inundated by the tsunami, past the preserved three-story Kesen Junior High School (気仙中学校), which had been flooded up to the roof at the mouth of the Kesen river.

I crossed the bridge and continued along the main road. On one side were bright yellow tractors dutifully waiting in the dirt and gravel before endless sections of barren fields with green mountains on the horizon; on the other was the wide mudbank between the ubiquitous seawall and the road still under construction with the recurring slogan “がんばろう! 岩手” (“Let’s go! Iwate”). Pausing to take in the view, I spotted what appeared to be fresh wild boar tracks in the wet sand. In the distance, white egrets and striated herons waded calmly in the marsh.

Almost a full decade after the 3.11 disaster, I was shocked by the void of what was ostensibly central Rikuzentakata. According to the map, I was in the right place, and yet I had the uncanny feeling of being in the middle of nowhere. Even after traveling through some of the hardest-hit areas in Miyagi prefecture, it was the first time I had witnessed the raw bareness of a tsunami-ravaged city, unable to imagine who and what had lived there before.

Across the road, I could see the ghostly skeleton of the former waterfront Shimojuku Settlement Promotion Housing (下宿定住促進住宅) with its remaining fifth-floor balcony rails, as the raging wave had gutted everything beneath them. Further down Route 45, I stopped to contemplate Tapic 45, the former Takata Matsubara Roadside Station built in the triangular form of a 19-meter-high staircase facing the sea. During the tsunami, three people had narrowly escaped the surge by running up to its slivery peak. Ironically, its faded façade was originally painted with the illustration of a giant wave; just below it, a red line marks the highest level of the floodwater at 14.5 meters.

Lessons from the 2011 Japanese Tsunami under a Miracle Pine

The Iwate Tsunami Memorial Museum (東日本大震災津波伝承館) opened on September 22, 2019. Most of what you see from the road is a vast parking lot, and it’s a fair guess that much of Rikuzentakata’s documentation and reconstruction efforts over the past decade have converged into what lies beyond it. As the centerpiece of Rikuzentakata’s sprawling memorial park, the museum is impressively comprehensive in its chronicling of what happened, what preceded, and what followed on March 11, 2011.

Japan is no stranger to earthquakes, and its northeastern Sanriku Coast is particularly prone to tsunamis. Iwate’s tsunami museum begins by placing the seismic events of 3.11 in the context of historical temblors around the world, but it spotlights the devastating Meiji Sanriku earthquake and tsunami that killed at least 22,000 people in Japan on June 15, 1896. Today relatively few people know much about it, let alone remember it. The survivors of March 11 want to make sure that the 2011 disaster does not sink into a black hole of history.

Already in the museum’s entrance lobby, an enlarged scrolling map of the Sanriku coastline highlights innumerable memorial sites along the tsunami’s path. Inside the exhibition hall, mangled emergency vehicles and other artifacts bear witness to the overwhelming force of the wave, while mounted wall panels full of numbers, diagrams, and comparisons analyze both the event and its aftermath. Laminated pages of survivors’ transcribed testimonies, some even translated into English, offer additional insight on an individual level.

For me, one of the most heartbreaking exhibits was also the most simple—before-and-after photos of specific places in Iwate prefecture, displayed successively on a single screen, captioned and dated without comment. Here were my missing images of Rikuzentakata: the downtown square with its clean streets and busy shopping arcades, and the dense matsubara of 70,000 pine trees.

A dedicated projection room screens a 12-minute montage of video footage from March 2011: the roaring tsunami witnessed from above and even head-on; ensuing annihilation across the coast, viewed both from the air and on the ground. Another room chronicles a vivid minute-by-minute narrative of the disaster through text and photographs, from the original 14:46 quake to the countless tsunami warnings, scrambled evacuations, tidal surge, massive destruction, search and rescue efforts…

“思い出して嫌だ (omoidashite yadda)” I overheard a woman say to her companion as they walked through the corridor. For her, these were painful memories. But these painful memories have also inspired many local survivors to become storytellers (語り部, kataribe), rising above the trauma of the tsunami by passing on its lessons.

Among the non-surviving human victims of the tsunami, 64% were over the age of 60. Only 14% were under the age of 40. Less than 6% were schoolchildren. In terms of building infrastructure, Japan was well prepared for earthquakes. Tohoku’s coastal districts had designated tsunami evacuation sites. Schools had safety protocols and drills. Beaches had seawalls.

So why did so many people die? As the museum presents the results of post-disaster surveys and analyses that attempt to answer this question, two prevailing trends emerge. First, the sheer intensity of the tsunami surpassed all expectations, was beyond imagination. And second, not everyone evacuated.

The Takata Matsubara Memorial Park (高田松原津波復興祈念公園) extends across the entire northern shore of Hirota Bay. Like Hiroshima’s monumental Peace Park, Rikuzentakata’s symbolically sprawling memorial park all but guarantees that the devastation of the 2011 tsunami will never be forgotten. Its natural attraction is the famous Miracle Pine, which was lavishly preserved after its inevitable death about a year after the disaster, standing by the crumpled ruins of the youth hostel that fortunately broke the tidal wave in front of it.

Rikuzentakata Youth Hostel

The day I visited the park was windy and solemn. Peregrine falcons flew overhead and perched on uprooted stumps while pochard ducks swam and dove into the rivulet. The central observation point offered a dramatic view of the city’s 12.5-meter-high seawall and sectioned fields of newly planted pine sprouts. One woman placed a bouquet of flowers on the commemorative stone platform facing the sea.

Resilience and Revival after the 2011 Tsunami in Rikuzentakata

Even Rikuzentakata’s mayor, Toba Futoshi, who lost his own wife in the tsunami, has admitted that the city’s reconstruction has been painfully slow. In March 2011, the fresh young mayor had only been in office for a few months, but by 2014 he oversaw the elevation of a new town center to 10 meters above sea level by transporting rocks from a hill across the Kesen river via a giant conveyor belt.

Although relatively sparse, these few commercial blocks now contain some independent shops and eateries, surrounded by new housing and a small playground, centered around a supermarket and shopping mall. As I wandered into the mall that evening, young people were busy installing a commemorative model of the lost city with flagged markers of former households. Right next door, residents browsed and teenagers studied inside a beautiful new library with warm wooden interiors. The library reserves a special section, including donations, for books and documents directly related to the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami.

I spent my last night in Rikuzentakata at Capital Hotel 1000, a former high-rise seafront hotel that was destroyed by the tsunami and subsequently rebuilt in a smaller version 1 kilometer inland. Since it opened in the middle of farmlands in November 2013, it has been a landmark symbol of the city’s recovery and determination to move forward.

After checking out on my final morning, I still had an hour left before the BRT bus was scheduled to arrive for the first leg of my long journey back to Tokyo. So I left my bag behind the reception, unfolded my bicycle, and ventured off for one last ride northward along the Sanriku coastline.

Exactly one hour later, I returned to the hotel, visibly out of breath. The staff smiled as she handed me my bag.

“Where did you go?” she asked.

“I cycled alongside the seawall,” I replied, “until I could see the sea.”

How to Get to the Sanriku Coast in Tohoku

To get to Onagawa from Tokyo, take the Hayabusa Shinkansen to Sendai (1.5 hours), transfer to the JR Senseki-Tohoku Line Rapid to Ishinomaki (1 hour), then take the JR Ishinomaki Line to Onagawa (25 minutes).

To get to Rikuzentakata from Tokyo, take the Hayabusa Shinkansen to Ichinoseki (2 hours), transfer to the JR Ofunato Line to Kesennuma (1.5 hours), then take the Ofunatosen-BRT bus to Rikuzentakata (35 minutes).

If you would like to extend your travels northward along the wild rias coast of Tohoku, continue on the Ofunatosen-BRT bus from Rikuzentakata to the end of the line (50 minutes) in Sakari (盛). From there you can board the 163-kilometer Sanriku Railway Rias Line, inaugurated in March 2019, which will take you on scenic routes through Kamaishi (釜石) and Miyako (宮古) all the way to Kuji (久慈).

The Sanriku Fukko (reconstruction) National Park (三陸復興国立公園) highlights more natural coastal attractions in Iwate and Miyagi prefectures, including the Oshika Peninsula around Onagawa.

Japan’s Sanriku Coast, in the more remote Tohoku region, may be forever changed by the tsunami of March 11, 2011, but every survivor has their own experience of the disaster, and residents have responded in various ways to rebuild their lives and community. By visiting sites of natural beauty along the wild rias coast, we can also witness the cities’ reconstruction and recovery with our own eyes, contribute to local economies, meet local communities, and remember never to underestimate the unseen forces of nature.