Compared to the generic experience of modern chain hotels, the Japanese ryokan experience offers travelers the opportunity to enjoy a unique lodging experience almost anywhere in Japan. Some tourists are put off by the idea of sleeping on the floor, sharing a bathroom, or the perceived language barriers when it comes to staying at ryokan 旅館, but often, these concerns pale in comparison to the pleasure that a good quality ryokan can offer.

I traveled to Fukushima City to attend and photograph the Iizaka Kenka Matsuri, one of the three main fighting festivals of its kind in all of Japan. My accommodations for this trip would be at Nakamuraya Ryokan in the Iizaka Onsen district of the city. Pulling up in front of the regal black and white building, I was met by Mr. Abe, who directed me to a parking space and took my heavy suitcase full of camera equipment.

Nakamuraya Ryokan 中村屋旅館 has quite a history in this town; built in 1688, it is the oldest ryokan in the area, and there are many. Iizaka Onsen is built on a hillside where a natural hot springs provides super-heated, mineral-infused water to the baths of many local establishments, including a host of ryokan. The Abe family purchased the ryokan in 1890 and the family has been running it consistently every since. In 1896, they added another wing to the original building, but the ryokan still modestly consists of only five main guest rooms. Solid as a rock, it has survived many natural disasters and is recognized as a Tangible Cultural Property of Japan.

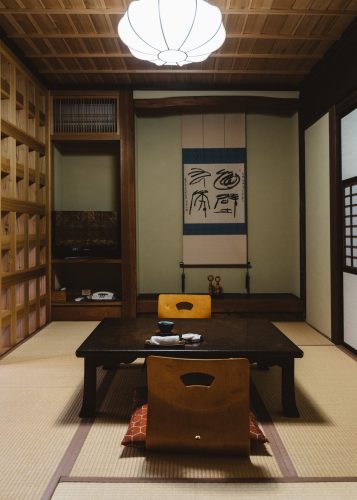

As you might expect from a 330-year-old establishment, the interior of Nakamuraya would impress any history buff. Vintage fixtures from sinks to bathroom doors are still part of the decor. The edges of the stairs are worn smooth from the thousands of feet that have traveled upon them. The lobby has a traditional sitting area consisting of tatami mats, a fire pit that warms a tea kettle suspended from the ceiling, and an Edo era screen so beautiful that people walking on the street outside routinely stop and ask to take a photo with it, which the Abes are more than happy to help with.

Mr. Abe showed me to my room, consisting of two separate tatami rooms, one for sleeping and another for dining and relaxing. A narrow area separated by shoji screens in the front window contained seating if I wanted to do people watching from my window (which a little later I would be very thankful for). Thanks to the gift of technology (Google Translate), my grade-school knowledge of Japanese and a few kind people who spoke some English, communication was not a problem at Nakamuraya. They really go out of their way to make things comfortable for you.

As with almost every ryokan, the bed was a futon on the tatami mat, but Nakamuraya provides a double thick futon to sleep on, and a heavy comforter to sandwich you in comfort. Between the futon and the ultra-soft yukata “pajamas,” I would later drift off into perfect uninterrupted sleep.

But that would come much later. First, I would have my dinner, a 13-course kaiseki 解析 feast, consisting of seasonal local foods from the agriculture-rich Fukushima area. It’s difficult to say whether the main course was the unagi (freshwater eel) grilled in a sweet sauce, the seasonal pickled kurage クラゲ (jellyfish) garnished with chrysanthemum petals, or the osekihan, a special rice with chestnut and red beans made specifically because of the Kenka Matsuri that evening. Suffice to say that everything was extremely fresh, delicious, and probably much more food than a person should eat in one sitting, especially if they are going out to photograph a festival soon afterward.

Dinner was pleasantly interrupted by a commotion outside my window. Mr. Abe returned to my room to inform me that participants in tonight’s festival were about to pass by on the street right in front of the ryokan. Though a crowd of people gathered on the sidewalk below, I had no problem snapping off a few great photos with nobody blocking my view. I finished my dinner and headed out to one of the most exciting festivals I had ever witnessed.

Returning to the ryokan after the festival tired and sweaty, I gathered my things and went down for a shower and ofuro (bath). For those who don’t like the idea of sharing a bathroom with strangers, Nakamuraya has you covered. The ryokan has two private baths, meaning the bath is all yours for the time you use it. You simply go into the dressing area and lock the door behind you and you have all the privacy of home. Because there are no time restrictions on when you can bathe and there are only a few guestrooms, getting a bath is never really a problem.

If you are unfamiliar with the concept of the Japanese bath, you wash yourself thoroughly in the shower area and only enter the bath once you are squeaky clean. The water from the Iizaka hot springs, however, is unusually hot and Nakamuraya provides a hose connected to a cold water source to manage the temperature. Even with the cold water to dilute it, the bath turned out to be too hot for me to get into for more than a minute or two, though I am a bit of a wimp when it comes to hot water.

Photo courtesy of Nakamuraya

The following morning, I awoke early to do a little exploring around the neighborhood that I didn’t have time to do the night before. A few meters down the street is Sabakoyu, a public bathhouse nearly as old as Nakamuraya. It has been helping its customers get clean since 1689, almost 90 years before there was a United States of America.

Because the area is famous for hot springs, many of the attractions in the area are hot springs related. Kyu-Horikiri-tei is a restored merchant family’s home with a huge open space garden for people to relax in. The garden includes a free shaded foot bath area for people to restore their tired feet.

After a stroll around the neighborhood, I returned to Nakamuraya for breakfast. While not as extravagant as dinner, breakfast is still an elaborate affair of traditional Japanese breakfast foods: miso soup, dried fish, a “radium egg” (the local name for eggs soft-boiled in onsen water), local vegetables, fresh tofu and of course, a lot of fluffy rice. The Japanese certainly know something about eating a well-balanced healthy breakfast.

Before leaving the ryokan, I stopped in the lobby to chat with Mrs. Abe and a group of older ladies who had been staying at ryokan with me. It turned out the ladies were three of six sisters who grew up in the neighboring village of Nakano, and I thought it was amazing that though they lived nearby, they chose to come to Nakamuraya for some rest and relaxation.

Getting to Nakamuraya

While I drove 3.5 hours to Fukushima from Tokyo, it would be far more convenient and comfortable to take the train. It takes a little over 2 hours by train from Tokyo Station to Iizaka Onsen Station using the Yamagata or Tohoku Shinkansen and transferring to the Izaka Line train at Fukushima Station. Arriving at the station, look for the sign pointing you in direction of Sabakoyu (the public bath), about 300m up a gray brick-lined street from the station. Nakamuraya is right before Sabakoyu on the right side of the street.

You can find all the useful information in English on this site.

Sponsored by Fukushima City Tourism and Convention Association.

[cft format=0]

No Comments yet!