For many travelers, one of the most unique and appealing experiences in Japan is sleeping on a futon 布団. This traditional Japanese bedding is often enjoyed when staying in a ryokan 旅館 (traditional Japanese inn) or a guesthouse, where washitsu 和室 (Japanese-style rooms) are common. Sleeping on a futon is considered an iconic part of Japanese culture, alongside other cultural staples like the kimono and sushi.

Unlike the widespread availability of Japanese food and goods worldwide, however, sleeping on a futon on a tatami floor 畳 is something most people in the West don’t have access to. While Japanese cuisine and many Japanese products are easily found globally, having tatami and futons in a typical Western home is still not practical.

What are the Origins of the Futon in Japan?

When we say futon, we mean the set of the cotton mattress and the comforter that goes on top, called shikubuton 敷布団 and kakebuton 掛布団, respectively. As traditional as it may seem, its widespread use is relatively recent. Its origins date back to the period of civil wars. But, its massive introduction into Japanese homes didn’t happen until the twentieth century.

During the Nara period (710-794), sleeping on a bed structure was a luxury that only the nobility could enjoy. The peasants would normally sleep on piles of straw, mats made of straw/rice plants, or directly on the ground. It was during this period that the oldest known beds arrived in Japan from China. The culture of the tatami also started to develop in the eighth century.

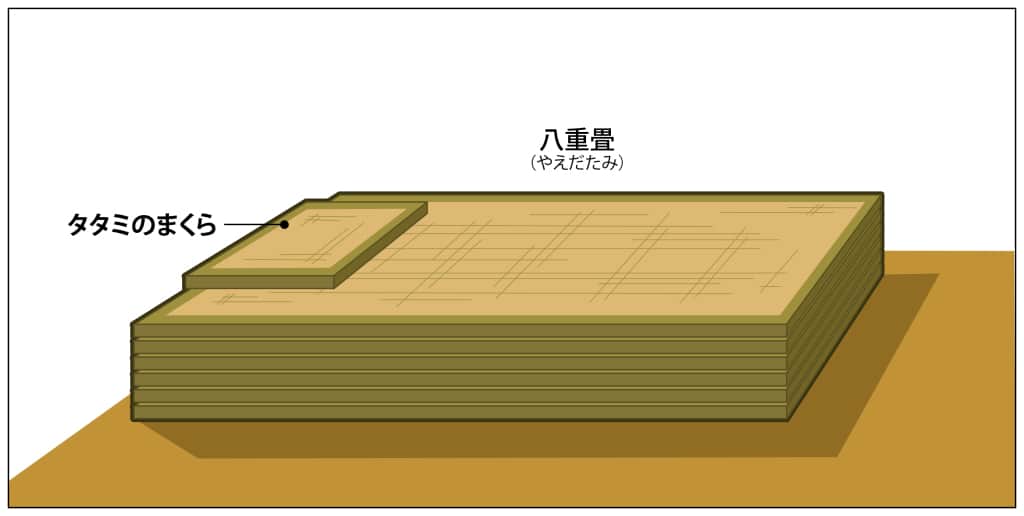

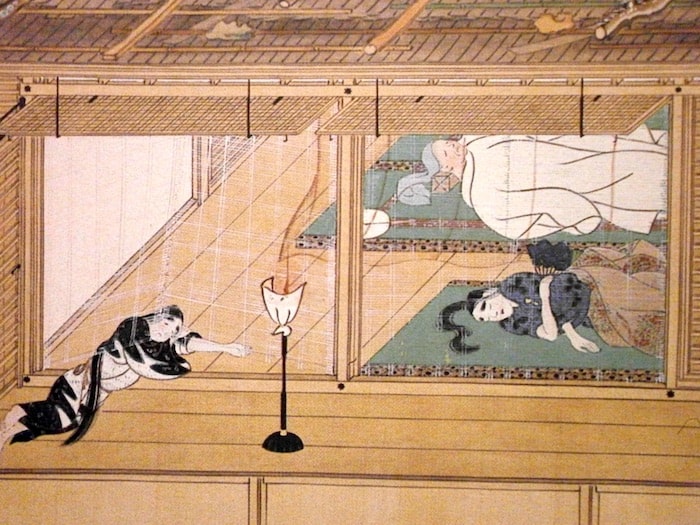

During the Heian period (794–1185), beds for the upper classes consisted of several tatami mats stacked on top of each other, called yaedatami 八重畳. The number of layers was proportional to the rank of the person in question. The pillow was a smaller piece made of the same material. Historical references and illustrations of the time show that the tatami didn’t cover the entire wooden floor and was just used as a resting surface.

Images: Edo Guide

Cotton as a Tool of Warfare

Cotton existed in Japan since the Heian era, but its initial cultivation was not successful. However, during the Age of Warring States (1467–1615), cotton demand exploded. Since it was still expensive and not easy to produce, its main usage went towards warfare material, such as the explosive fuses on bombs and the slow-burning cord to ignite matchlock guns. Secondarily, for flags and soldiers’ clothing. Its use as a textile material for normal clothing was quite residual.

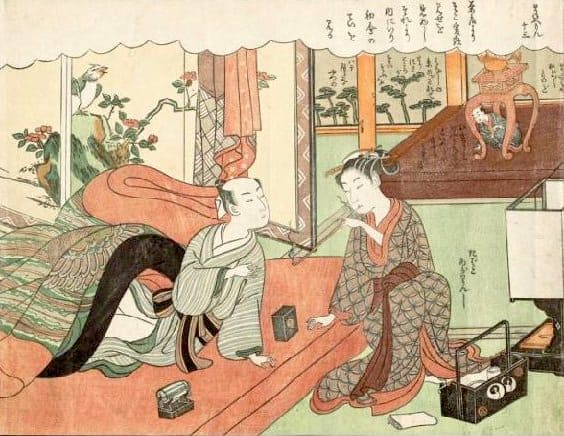

The beginning of the Edo period (1603–1868) saw the demand for cotton for warfare decrease, and thus, cotton began to spread slowly among the population. At the time, the norm was to sleep naked or just covered with the same clothes worn during the day. So an increase in cotton usage led to the development of padded kimonos to sleep. The first Japanese pajamas were called kaimaki futon 掻巻布団 and sometimes also made of linen.

The First Futons: A Luxury for Only a Few

As for sleeping surfaces, what common people used were the so-called senbei futons 煎餅布団. It was a humorous nod to the typical Japanese rice crackers of the same name. Those futons had so little cotton, so they would easily become hard and stiff. Nice and cushioned quilted futons were still the only handmade and extremely luxurious items. Only the upper classes or the most expensive courtesans could afford them.

It was only at the end of the nineteenth century that shops dedicated to selling futons began to appear. Even so, they were still an item within reach of few. The appearance of cheaper imported cotton allowed greater access to it. Particularly during the post-war period, finally putting an end to meant that cotton futons finally ceased to be a status symbol and became a commonly used item by the general population.

Futon Usage in the West

Futons became known in the West during the second half of the twentieth century, thanks to increased international travel. Those who visited Japan and appreciated this different way of sleeping sometimes brought futons back with them or tried to learn and adapt them. But these differ from the originals in that they are usually somewhat thicker (about halfway between a Japanese futon and a mattress) to accommodate the average Western audience.

On the other hand, Western homes normally do not employ tatami, and the futons do not usually go on the floor but rather in a bed or sofa-bed structure. They are especially popular for the latter because of their ease of folding.

Care and Maintenance: How are Futons Made?

Traditional futons are usually handmade and 100% cotton. But nowadays, several manufacturers also incorporate materials such as polyester, latex, or polyurethane foam. The use of synthetic materials is not necessarily bad, since they also help modulate comfort and facilitate maintenance, as they do not absorb the same moisture levels as cotton.

The popularization of cotton futons also generated uses and customs that ended up influencing the social landscape. Smaller homes and apartments benefited from the space-saving advantages and convenience of a futon. Also, the need to move and air the futons in the sun is one reason why almost all Japanese homes need to have south-facing balconies. This ensures sufficient sun exposure to take advantage of its anti-bacterial properties.

Similarly, the custom of storing futons in cabinets derived from the same cause and was a custom that began to spread in the early twentieth century. Moisture and tatami are a bad combination. For this reason, keeping the futon in the same position all day is an invitation to unwanted guests in our precious resting spot.

What Advantages Are Derived from Sleeping on the Ground?

For many years, many people’s personal experiences suggested that sleeping on firmer surfaces is more beneficial to our spine. Until 2005, however, there was little empirical evidence in either direction. That year, researchers published the first clinical trial that shed more light on this regard. The researchers evaluated the results of sleeping at different levels of firmness for patients with chronic back pain problems. With a firmness scale from 1 to 10 (less firm to more firm), levels 6–7 obtained the best results. Level 8 followed them in second place. Therefore, the benefits of greater firmness, without going to extremes, became evident.

That is, sleeping on a futon on the floor does not cause back pain. Although back pain among the Japanese population is as prevalent as in any other developed country, there are more factors at play than just bedroom habits. In any case, the custom of sleeping on a futon ensures that it does not get worse.

What is the Future of the Futon Culture?

There is no indication that the use of futons may be in danger. Even when the use of tatami floors is clearly in decline, it is still common for an apartment with wooden floors or other materials to have a tatami bedroom to allow tenants to sleep on a futon. This is not just about the cultural factor and the health concerns— there is also a practical side to this. Being able to store the futon and have the extra space is a valuable advantage in a place where the usual dimensions of homes are not too large. Are you willing to give it a try?

Originally written in November 2020

Cover photo: Todd Fong

Aloha Voyapon, I believe “Edo period (1603–1968)” should be 1868. Good article on futon; keep up the great work!