What does Hello Kitty have to do with the US-Japan bilateral Treaty of Cooperation and Security and the May 68 protests in France? How is it possible that the French Baroque and Rococo aesthetics of the 17th and 18th centuries inspired a counter-cultural rebellion in Japan in the second half of the 20th century?

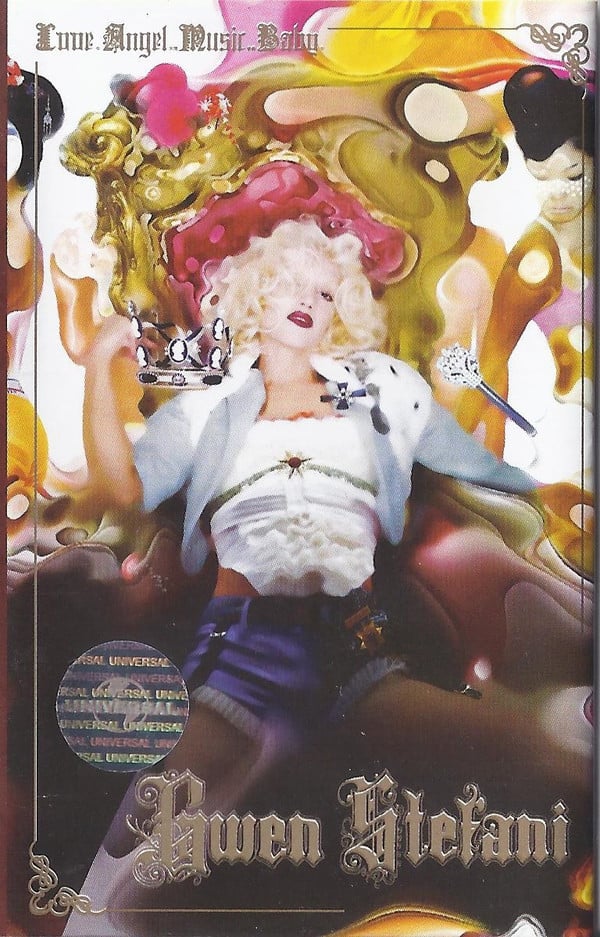

Fast forward to 2004 for a moment. Gwen Stefani’s debut solo album surprised the world of Western commercial pop and placed the name Harajuku (原宿) on everyone’s lips. No Doubt’s ex-singer revealed that she had fallen head over heels at the feet of the famous neighbourhood’s eccentric street styles and made sure to prove it enthusiastically. Not only had she incorporated a group of Japanese backup dancers into all of her performances, but she also paid multiple tributes to this striking aesthetic amalgamation in several of her music videos of what is now known as her Harajuku Girls phase.

Suddenly, the subculture that had been brewing around Takeshita Dori since the 1980s left the aesthetic niche and settled comfortably into the mainstream of Western culture. In the same wave, Kawaii as a concept accelerated its introduction beyond fans of Japanese culture, as the main Japanese aesthetic category between cute and cool. Harajuku and all of its Kawaii paraphernalia were here to stay in the collective world consciousness.

But global fame and jump into mass culture come with a hefty price: loss of meaning and context. Kawaii is one of the best known Japanese words, but at the same time, its complex meaning gets lost in translation. It is often interpreted as something cute or tender, but in reality, the word also alludes to the psychological state of the person who is experiencing something kawaii as well as the atmosphere or the surroundings. Its evolution as a multifaceted aesthetic concept can also be explained because of its strong emotional load.

Harajuku’s Kawaii: It all started with a shop

For many years, Sebastian Masuda has been one of the biggest creative driving forces behind the impulse of the particular type of Kawaii culture that developed in Harajuku. The work he’s carried out to explain this movement to the rest of the world earned him the title of Cultural Envoy of Japan in 2017. He jumped into the spotlight thanks to the artistic production of Kyary Pamyu Pamyu‘s music videos, but since the ’90s, he has already been involved with groups of avant-garde tendencies in theatre and contemporary art.

However, it was not until 1995 that his cultural legacy began to crystallize. That was the year he decided to open 6%DOKIDOKI in Harajuku, an extravagant clothing and accessories store where his designs share space with the most striking items of independent brands from other countries.

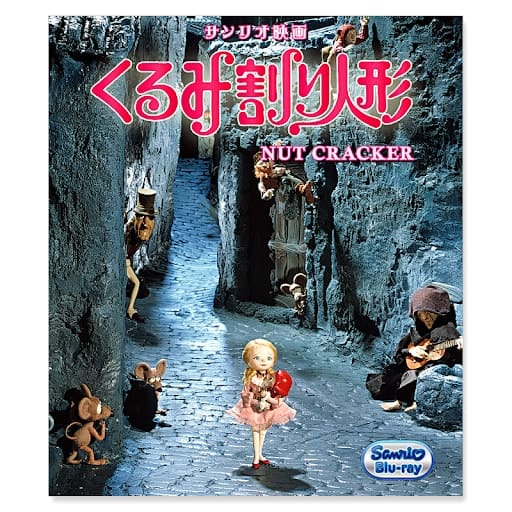

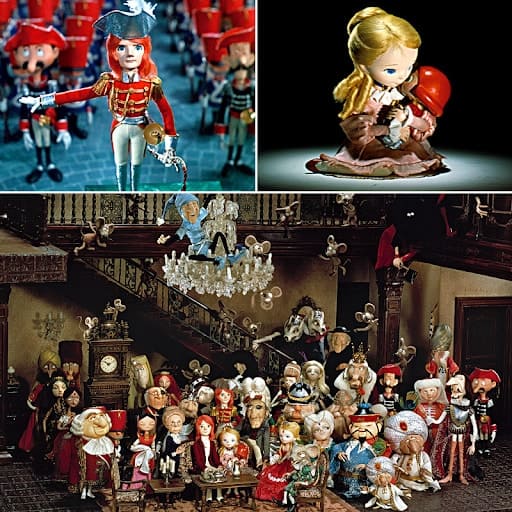

Hello Kitty was to blame for everything. Or rather, its creator company Sanrio through another of its productions. In 1979 Sanrio produced Nutcracker Fantasy, a stop-motion animation film that has been cited by Masuda himself as one of his most important sources of inspiration. All it takes is to watch some of the trailers on Youtube and the promotional images to see the influence on the artist’s later work.

A closer relationship with the audience and the establishment of a community were his main motivations for opening the shop. This is how he explains it:

“I moved into the shop as a means of expression because it is a continuous place where complete strangers can directly evaluate my work (products) on a buy-sell basis, as opposed to a stage or an exhibition, which has a more intimate feel and a shorter duration.”

The commercial versus the artistic as a direct form of relationship with the public was already an idea that had been floating around in Japanese artists’ circles since the 1960s. Postmodern criticism brought about paradigm shifts in all manifestations of visual culture, blurring the boundaries between art and design. Artistic production began to move out of museums and galleries and into public and commercial spaces. Design ceased to serve first the object’s functional purpose to become considered another form of communication tool.

Under this philosophy, 6%DOKIDOKI is born mirroring the neighborhood’s soul and the artist’s aesthetic values. It also functions as a vehicle for the dissemination of local culture. On various occasions, the shop staff or groups of local young people have also participated in the events that Sebastian Masuda has carried out, in Japan or abroad. Art as a personal expression has always been the leitmotif in his work.

A perfect storm

However, his shop’s commercial success is strongly linked to several exceptional circumstances that transformed Japan in the 80s into the perfect setting for the combination of important artistic movements and extreme consumer habits. The deep convulsions of 1968 not only shook Europe, but its shockwave was felt with great force in Japan. These were years of cultural and artistic effervescence due to the influence of counter-cultural movements in the rest of the world, which inspired anti-authoritarian feelings in Japanese youth. The bilateral defense agreements with the United States generated waves of student protests since the beginning of the 60s, framed by anti-war sentiment and the perception of increasingly reduced autonomy in favor of unilateral support for the American army.

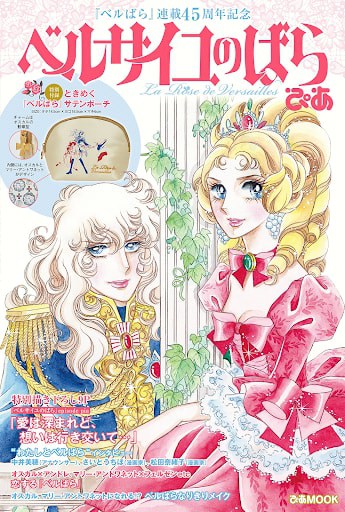

Social reform movements such as feminism also resonated strongly during this period. Ryoko Ikeda, the author of the manga The Rose of Versailles, one of the most emblematic titles of the Shoujo genre, had already stated that she drew her inspiration from second-wave feminism during the creation of her characters. Especially the fictional figure of Lady Oscar and her subversion of traditional gender roles. From the beginning of her publication in 1972, she soon made waves among her readers. Her representation of revolutionary values amidst the Baroque and Rococo aesthetics of Marie Antoinette’s court transformed the work into a style icon that channeled the feelings of an entire generation.

The work’s cultural impact was also felt among many fashion designers, whose proposals quickly connected with the female audience and offered one (out of many) aesthetic platform for the use of fashion as a form of protest. This is the genesis of the Harajuku Lolita and its aesthetic appropriation of the French Baroque and Rococo as another manifestation of the Kawaii within the context of feminist demands.

The kitsch, the ridiculous, and the excessive constitute a resounding and eloquent f-bomb to prevailing social pressures. While punk fashion in the West sought to generate visual shock through leather, piercings, and sloppy looks, the so-called Lolitas resorted to lace and excess as their weapons of choice. Two apparently opposing manifestations were after the same effect: the rejection of traditional values. What was particular about the Japanese case was how hedonistic consumerism became a revolutionary act because it went diametrically against the values that require an adult woman to be a pillar of the family and a model of responsibility and spotless moral values. To forget her individuality beyond her expected dimension of a wife and a devoted mother. For whom a grey and sacrificial maturity means death in life, a childish behavior as refuge means will turn into a survival strategy.

Paradoxically, political and social discontent occurred during times of strong economic growth. In this context, companies such as Sanrio were quick to recognize and capitalize on these new consumer trends arising from this discontent. In other words, the young Masuda would not have had his source of aesthetic inspiration had Sanrio not taken advantage of this climate to give a commercial response to a growing demand for tender and childish articles whose clientele was not necessarily children.

The development of this Kawaii culture (and its various derivatives) is therefore only understood in a very specific context. It is a type of consumer culture that can only be developed in flourishing times. A bonanza that is the product of an economic miracle loaded with social costs: personal sacrifices, very long working hours, and a workforce condemned to suffer under a strict hierarchy. The infamy of Japanese work culture persists to this day.

Fashion and art as a personal expression

Within this context, fashion also acts as a coping mechanism for emotions and psychological issues. Human beings function within spheres of context that affect our cognitive processes. We do not behave in the same way in a temple, a party, or an office. We do not act the same way sitting upright as we do leaning on a sofa. Likewise, the psychological effects of the clothes we wear are a widely studied phenomenon. Clothing is not neutral. This is the way design exerts its social influence. In a country where emotional instability is perceived as a weakness, these manifestations are also an act of defiance. This is exactly one of the ideas that Sebastian Masuda expressed in his first exhibition in New York:

“One must understand that in Japan, therapy and psychological outlets are not as acceptable as they are in the United States,” Masuda explains in his artist statement. “The majority of the time, these girls do not fit in with their classmates and community. Harajuku is not only a place where they can be different without consequence — it is also a place that provides fashion alternatives for girls to express dark emotions in flamboyant, alternative styles.

This way, the dark, the ironic, and the grotesque also play a part within an aesthetic that strives to express deep and complex emotions. Harajuku’s Kawaii is the culmination of postmodern’s incorporation of avant-garde artistic movements, while still employing concepts rooted in Japanese culture.

The Professor of the School of Arts and Letters at Meiji University, Ujitaka Ito, argues that:

“kawaii” encompasses a nuance of grotesque. What is regarded as “kawaii” does not usually have a perfect shape. For instance, most people consider a baby “kawaii.” A baby is one of the typical objects which most people consider “kawaii.” However, if an adult maintained a body proportional to that of a baby, we would surely feel the person grotesque, attributing this feeling to his/her extremely disproportional body shape. It is the same as “kawaii” characters of manga (Japanese comic books) or anime (a style of animation originating in Japan). They have enormously large eyes, or their heads are oversized. They are considerably deformed.

Kawaii Monster Cafe, a frenzy of Harajuku’s kawaii

In 2015, Masuda took one step further all the ideas he had showcased the year before in New York. Kawaii Monster Cafe‘s opening was an opportunity to have a permanent art installation representing the philosophy that has characterized his work until its closure at the end of January 2021. It was the creation of a parallel world self-contained in a symbolic way inside a monster’s stomach. A microcosm free of expectations of seriousness, harmony, and hypocrisy where its participants could manifest themselves openly and directly. The interaction with the audience through the shows was a fundamental part of the ideas behind the whole concept.

In the same way, the thematic choice for their night shows was not fortuitous. Oirans, burlesque dancers, or drag queens. Entertainment figures that are found on the cultural fringes. Especially the latter if we take into account the context of Japanese social conservatism. Although the historical tradition has always had men playing female roles in Kabuki, current trends in drag queen culture have very different connotations.

It may not seem so relevant that LGBT-themed shows take place in a neighbourhood known for its independence and originality. But in Tokyo, LGBT-related entertainment is often restricted to Nishi Shinjuku and is still treated as an underground scene. Its presence in such a famous, if a unique, place as Kawaii Monster Cafe is an important step in visibility.

To this day, it would be naive to assume that all individuals wearing outlandish clothing are trying to communicate their social discontent. The popularization of any aesthetic movement always entails its simplification or trivialization. Once anchored in the mainstream, it’s normal to see it losing part of its original meaning and having people displaying that particular fashion simply because they like it without necessarily sharing the same core values. We are not here to defend purism but to point out that it is not necessary to share the same aesthetic taste for Harajuku Kawaii in order to recognize its meaning. Beyond what may look weird and strident, a simple desire to attract attention, there is a whole artistic and cultural movement behind it that deserves to be vindicated.

No Comments yet!