Volcanoes are so commonplace in Japan tourists tend to forget the dangers posed by infrequent eruptions and earthquakes. However, Mount Aso is not your typical hole in the ground. As all that remains of a once-massive super volcano, Aso poses its own kind of risks for travelers.

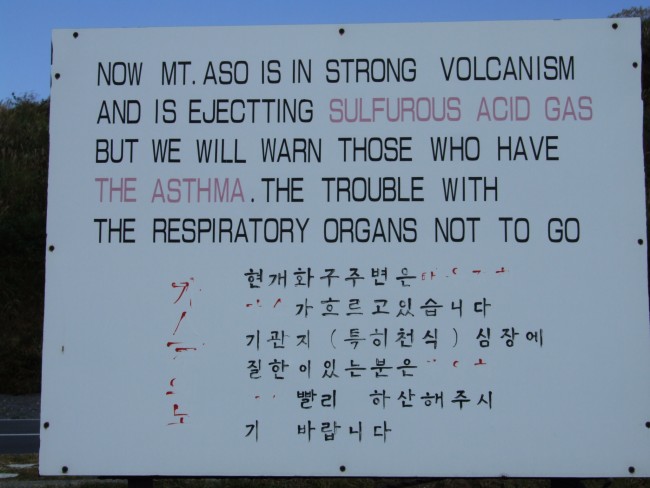

The wind, funneled between the mountains, cuts across exposed flesh and leaves it feeling raw; the chill, distinctive at this altitude, numbs hands and causes fingers to swell; the sulfuric plume from the caldera, constantly changing directions, could make a hiker suffocate in a matter of seconds. A unique death, to be sure, but not very likely.

The volcano on Sakurajima in southern Kagoshima has certainly made locals there numb to the idea. Just like the Romans in the shadow of ancient Vesuvius, waking up to a smoke plume scattering ash over the city in the summer months is as natural as seeing the sun rise… much more common than catching a glimpse of magma or sulfuric rain. There aren’t nearly as many negative feelings about these mountains of fire in Japan. People climb Mt. Fuji every day, not realizing it could be set off by the slightest whim of Mother Nature. And, you’d be hard-pressed to find any man, woman, or child who hasn’t partaken of one of the numerous onsen (hot springs) the land offers in exchange for the ever-turbulent earth.

Volcanoes are respected as forces of nature. In Japan, they are also monuments to national pride, creations of nature as valued as the beautiful cherry blossom trees peaking in April.

The mountain peaks at Mount Aso (Aso-san), were once one of the largest volcanoes in the world. If you’d have glimpsed it thousands of years ago, it would have been a vision to make even Dante nostalgic for the 9th circle: dozens of smaller eruptions, venting the pressure from the larger magma source; yellow sulfur scattered across the landscape, burning blue just at the edge of the tree line. The explosions eventually occurred too quickly and frequently, causing the entire mountain to collapse in on itself and creating the largest caldera in recorded history.

Nature personified, the Japanese see the various peaks of Aso volcano as resembling a sleeping Buddha, with the active peak Nakadake as his navel. An image of such harmony, belying the essence of such mountains, explains much about local culture: fire festivals are held every year to pay homage to this awesome force, fields burned to imitate lava slowly trickling into inhabited areas. Even the edges of the crater, where the plume and burning sulfur can be seen up close, are easily accessible by car or ropeway. Thousands come to look down towards the largest boiling hot springs Japan has to offer. Unfortunately, this particular pool, a mere hundred meters below the observation deck, would do little in the way to satisfy stressed Tokyo salarymen.

Blankets of sunlight pierce the cloud cover, sweeping across the lava fields. They reveal the ancient trenches that allowed the massive lake, created in the wake of the caldera, to drain so many thousands of years ago. A beach remains, consisting of black volcanic sand; the wind does very little to let me appreciate its splendor, casting storm after storm at my face, tearing the moisture from my skin. Most prefer to walk backwards.

Many still don’t completely understand the reverence surrounding Aso and its volcano. Most – children dragged there by overeager parents; French tourists – come for the smoke, but stay for the grassy fields, horseback rides, and purple flowery meadows near the museum. Everything once considered “exotic” and “unreachable” is now entirely within reach: men can pay to go into space, an Everest tour is available with the click of a mouse, and aircraft will take travelers across the globe in less than two days.

As one can later ease into the not-so-tepid bath of a nearby hot spring, few travelers to Japan seeking a volcano experience the feeling of a warm onsen in the cold mountain air, followed by a soothing bottle of milk. It’s all made possible by the unseen aspects of Aso… the hidden chambers of naturally heated water, the cows grazing in nutrient-rich volcanic soil out of sight, and the majesty of the mountain as a whole.

Mount Aso Access:

A roughly hourly bus to the Nakadake Crater takes 30-40 minutes from JR Aso Station, and a one-way trip costs 650 yen. You can then walk or take the 1,200 Yen ropeway to the crater.

[cft format=0]

No Comments yet!