I can’t help but feel overcome with nostalgia when I think about Oji (王子). It was in this neighbourhood where I spent my first five months after moving to Tokyo (東京), and thus, was my first experience exploring a local area within this megalopolis. During previous years, my Tokyo visits, albeit fun, mostly consisted of hurried marathons between famous commercial districts and touristic regions.

It was precisely my desire to experience life as a resident that brought me to Japan. According to the internet ‘tourist-sphere,’ Oji was the pulse of this vibrant city. And Oji became a part of my every-day life– exploring local shops, craft markets, hidden restaurants and taking bike rides throughout the neighbourhood. It felt like that there was no life beyond the north of Ikebukuro (池袋).

The Garden Where East Meets West

After acquiring a mamachari (ママチャリ, the Japanese nickname for the cheap bikes used by many to get around the city), I chose the beautiful Kyu-Furukawa Gardens (旧古河庭園) as one of my first forays into the area. Admission costs 150 yen (or 400 yen for a combined ticket with Rikugien gardens). It used to be the former residence of the Furukawa family, one of the most prominent since the Meiji era and founder of one of today’s main industrial groups.

The first thing that struck me was the monumental English style mansion next to the French style rose garden. As I sat in the small observation pavilion to relax and contemplate the views, I was momentarily taken back to the turn of the century Japan.

I imagined myself in the shoes of the English architect Josiah Conder, the creator of the complex. Considered one of the fathers of modern Japanese architecture, I tried to envision what it must have been like amid the cultural effervescence of Japan’s modernization and its adoption of many western facets.

From the mansion, I went down narrow stairs and entered into a radically different world. The delicate balance between both environments became crystal clear. The geometric precision of the rose garden is a stark contrast with the sinuous and asymmetric strokes of the Japanese garden. The garden is a creation of Niwashi Ueji, a garden designer from Kyoto and master of distilling harmony from (im)perfection.

Kyu-Furukawa Gardens

Kyu-Furukawa Gardens

TOURIST ATTRACTION- 1 Chome-27-39 Nishigahara, Kita City, Tokyo 114-0024, Japan

- ★★★★☆

Nostalgia in a Traditional Sweets Shop

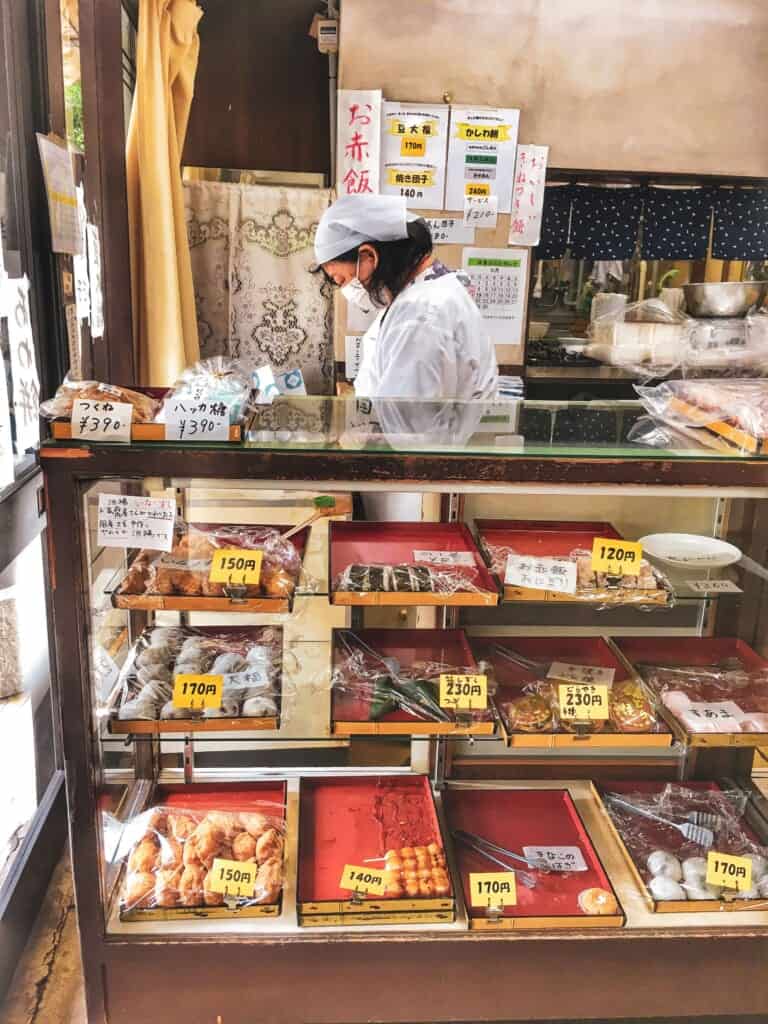

Next, after leaving the gardens, I walked towards the northwest side along Hongo Dori Avenue (本郷通り). Along the way, I happened upon Hiratsuka Tei (平塚亭), a small traditional sweets shop founded in 1933. Its popularity is due to its nostalgic style and frequent appearance in “Mitsuhiko Asami” novel series (later adapted to a TV drama). Its main character, a detective, is a neighbourhood resident and regular customer. It’s the perfect stop to get sweets and continue down the road to Asukayama Park, where locals and visitors alike can enjoy a picnic.

Hiratsuka-tei Tsuruoka

Hiratsuka-tei Tsuruoka

FOOD- 1 Chome-47-2 Kaminakazato, Kita City, Tokyo 114-0016, Japan

- ★★★★☆

Asukayama, One of the First Parks in Tokyo

Asukayama Park (飛鳥山公園, Asukayama Kouen) is one of the most iconic spots in Oji for historical and aesthetic reasons. It appeared among the “100 Most Famous Edo Views” when Shogun Yoshimune Tokugawa (将軍徳川吉宗) ordered the plantation of 1,270 cherry trees in 1720. The park quickly became an obligatory visit during the Hanami season among Edo inhabitants. Despite keeping only half the original number of cherry trees today, it’s still one of many Tokyoites’ favourite cherry blossom viewing spots. In summer, it’s a well-visited spot for hydrangeas lovers. During the height of the season, many visitors gather to immortalize the famous summer flowers that grow along the narrow passage between the park and train tracks.

Here’s a small bit of trivia: Between 1970 and 1993, there was a spinning cafe of 40m in height, called the Sky Lounge. Popularly known as the Asukayama Tower, visitors were able to enjoy coffee and tea while looking over the park’s panoramic views. Unsurprisingly, it was one of the highlights of the area. In 1993, infrastructural decay and new buildings in the area resulted in the demolition of the structure.

Asukayama Park

Asukayama Park

PARK- 1 Chome-1-3 Oji, Kita City, Tokyo 114-0002, Japan

- ★★★★☆

There is a free mini-monorail at the northwest end of the park. It’s perfect for those who prefer to avoid the steep stairs between the park and the street. It’s also the closest route to the Toden-Arakawa tram line and the Oji Station via Namboku Line (Tokyo Metro) or Keihin-Tohoku line (JR).

Next, after I crossed Hongo Dori just a few meters away from the park, is what was to become my absolute favourite corner.

The Silent Aquatic Park and the Survivor Ginkgo

I’m not sure how to start explaining the sensations I get when I think about this small space of singular and melancholic beauty. Otonashi Shinsui Park (音無親水公園 Otonashi Shinsui Kouen) means ‘silent aquatic park.’ To me, the parks’ whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Otonashi Shinsui Park had initially been the confluence point where the Shakujii River (石神井川, Shakujii-Gawa) flowed into the Sumida River (隅田川, Sumida-Gawa). During the postwar urban development era, it became so contaminated that authorities saw no other option than to, almost literally, ‘sweep it under the carpet.’ Underground pipelines were installed under Asukayama to divert the polluted river, leaving the park waterless.

Now, nothing remains under the bridges, but stones left in organized chaos. To me, that landscape looks like something straight out of a Surrealist painting. Only on rainy days does the water trickle through the park, and remind us of its testimony of the price of postwar urban development.

I think about the contrast of the park with the magnificent ginkgo (銀杏, ichou) that serves as the parks’ side companion. For over 600 years, it has lived through the Meiji Restoration and two World Wars. It stays undaunted, facing the daily murmur of workers and students coming and going every day.

Otonashi Water Park

Otonashi Water Park

PARK- 1 Chome Ojihoncho, Kita City, Tokyo 114-0022, Japan

- ★★★★☆

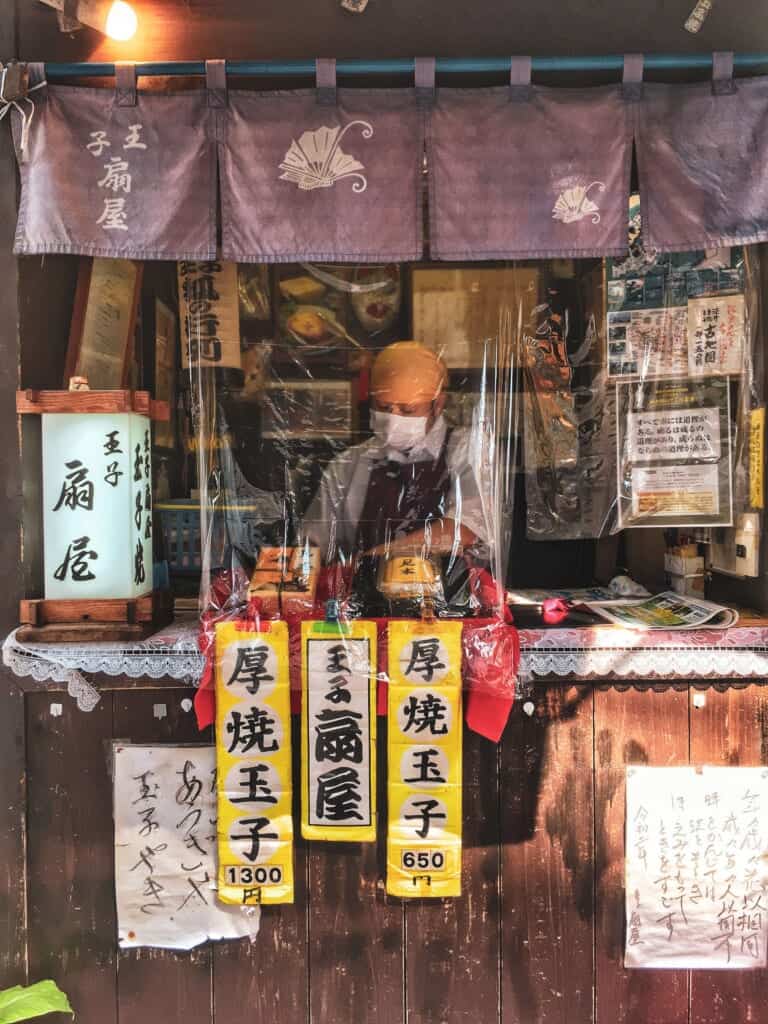

Ougiya, a 300-Year-Old Tamagoyaki Omelette Shop

Nearby is the 300-year-old Ougiya (扇屋), an unassuming and almost hidden tamagoyaki (卵焼き, sweet omelette) stall. The everlasting and transient got tangled up in my head as I sat and enjoyed my delicious omelette and watched people pass by the silent stones.

Founded in 1648, this omelette shop inspired a well-known rakugo (落語, a type of classical theatre that consists of comedy monologues) story called “Oji’s Fox” (王子の狐, Ouji no kitsune). In this story, a man tricks a fox into entering the restaurant.

In its heyday, Ougiya used to be a restaurant several stories high in the same location. Unfortunately, they decided to close in 2008 and keep the memory alive with the small stall.

Temples With Over A Thousand Years of History

As I continued up the stairs towards the ginkgo tree, I found myself in front of Oji Shrine (王子神社, Oji Jinja), one of the ten main shrines of Tokyo, and one of the oldest. The exact year of the shrine’s establishment is unknown but estimated at around 1053 to 1065. Its followers pray here for protection against natural disasters and ensure safe pregnancies.

A bit further to the northwest is the other face of this sacred area and symbol of the neighbourhood. Oji Inari Shrine (王子稲荷神社, Oji Inari Jinja) is dedicated to Inari, the famous fox deity, and protector of the good fortune, harvest, business and industry. Its exact foundation year is also unknown but is considered one of the most important shrines in the Kanto area since the Edo period.

Oji Shrine

Oji Shrine

TOURIST ATTRACTION- 1 Chome-1-12 Ojihoncho, Kita City, Tokyo 114-0022, Japan

- ★★★★☆

Ōji Inari Shrine

Ōji Inari Shrine

TOURIST ATTRACTION- 1 Chome-12-26 Kishimachi, Kita City, Tokyo 114-0021, Japan

- ★★★★☆

During the past few years, Oji Inari Shrine has enjoyed a renewed popularity thanks to the celebration of the Fox Parade (狐の行列, Kitsune no Gyōretsu). This relatively recent tradition was brought to life after several famous legends of Kanto-area foxes that gather on New Year’s Eve, inspired the locals to organize the parade.

The Exuberant Urban Oasis of Nanushinotaki Park

Next is the Nanushinotaki Park (名主の滝公園 Nanushinotaki Koen), a place that works its magic to convince me I’m in a remote natural site.

With the relaxing sound of its waterfall in the background, I fantasized about being inside the sacred forest of Princess Mononoke (a Studio Ghibli movie). At any moment, I felt I could have been surprised by a Kodama, the small forest spirit that appears within Japanese folklore.

Nanushinotaki Park

Nanushinotaki Park

PARK- 1 Chome-15-25 Kishimachi, Kita City, Tokyo 114-0021, Japan

- ★★★☆☆

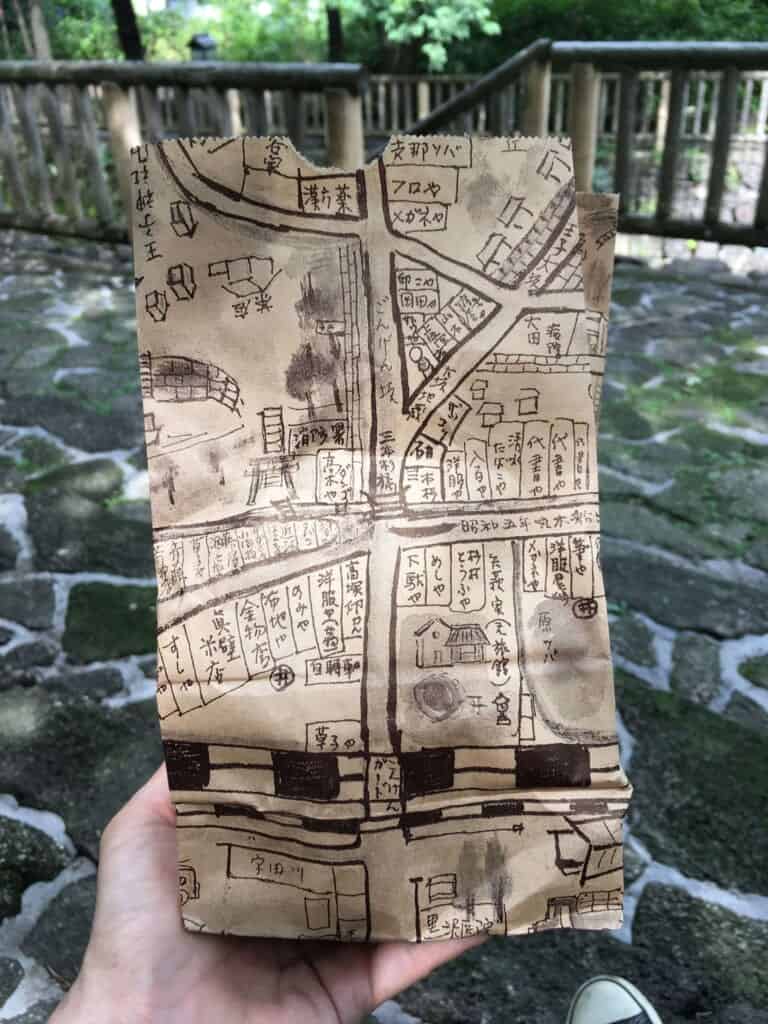

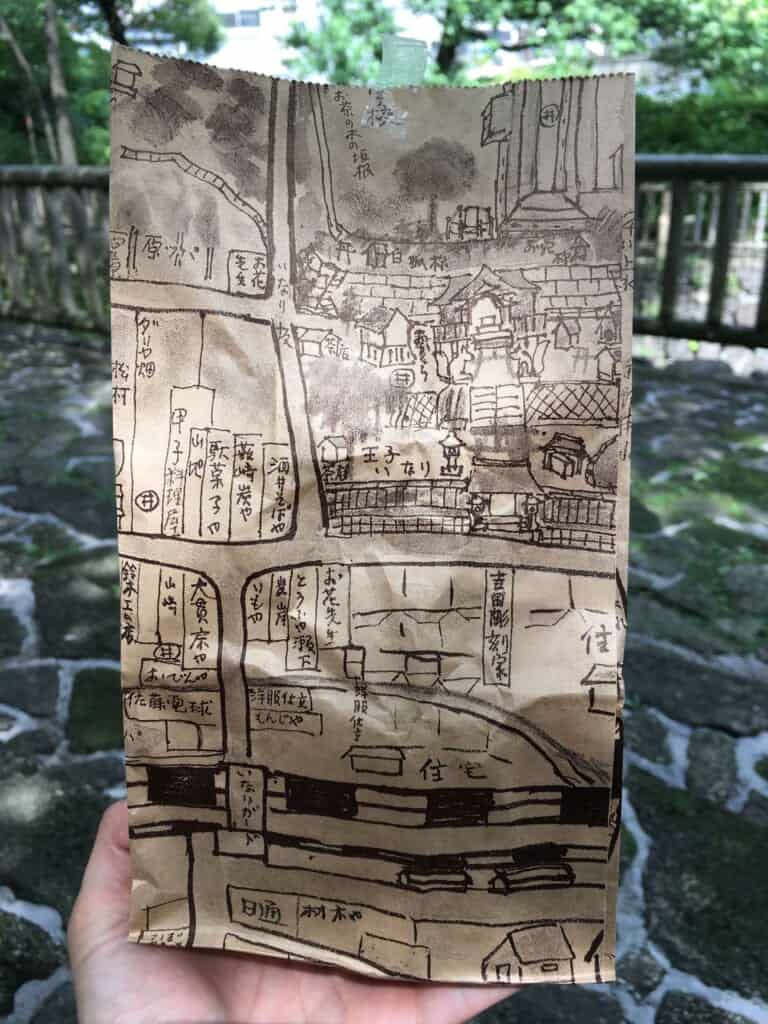

Very close by is another of what is to become one of my favourite shops in the area. Ishinabe Kuzumochi (石鍋久寿餅) has over 130 years of history and have been crafting sweets with the same techniques since the Meiji Era.

A lovely detail from this shop is the design of their paper bag: an old-style neighbourhood map! It’s a clever promotion tactic that also honours the area and its rich history.

Skyhigh Delicacies and Panoramic Views at Hokutopia

Ok. Until now, I’ve only talked about sweets. So, it’s about time I recommend my favourite place for a nice lunch or dinner. Very close to Oji station, I came across Hokutopia (北とぴあ), a multi-use building that includes a concert hall, conference room, a planetarium, and a free observation deck on the 17th floor. I was able to enjoy panoramic views of the area, particularly of Asukayama Park.

On this floor, there is a traditional Japanese food restaurant called Sankaitei (山海亭). It can’t boast about a hundred-year-old history, but its exceptional location and good price-quality relationship are reason enough to make it an obligatory visit.

The Fox Deity Shop and Shrine

A few streets away, I found a shop that I feel sums up the entire neighbourhood atmosphere. Yamawa (ヤマワ陶器) is a pottery and home goods shop with a large collection of fox masks. It also has tons of different items that feature representations of the revered Inari deity. There are also Gashapon (small collectable toys from vending machines, usually between 300 and 500 yen each) that share the same theme.

Across Yamawa is a picturesque mini-shrine of Shōzoku Inari-jinja Shrine (装束稲荷神社). According to legend, there was an Enoki tree where Kanto foxes gathered to dress up as humans before the parade.

For those still feeling energetic, I’d recommend visiting the lively izakayas ambience in the nearby Akabane neighbourhood.

I’d be lying if I said that I have covered everything Oji has to offer. I have spoken of places I believe are essential to visit while in Oji, and I hope that I have inspired others to make their discoveries in the area. The north of Tokyo still maintains a local neighbourhood charm that has not succumbed to mass tourism. It offers a unique experience for those looking to get to know a more original and authentic Tokyo. And in my opinion, Oji is a wonderful place to do this.

How to Get to Oji

As the name indicates, the closest station is Oji Station (王子駅), which runs along the JR Keihin-Tohoku line or on the Tokyo-Metro Namboku line. It is also possible to reach the Oji Ekimae tram station through the Toden-Arakawa line.