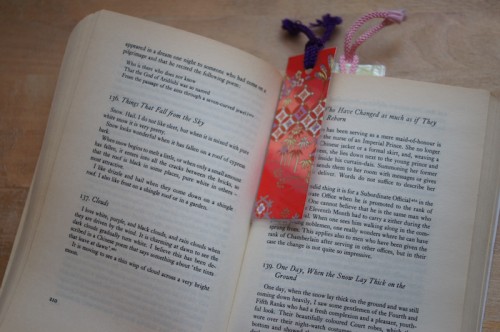

Reading classical Japanese literature might sound like a daunting challenge, comparable to Chaucer, Shakespeare or the ancient Greeks. But don’t be too quick to judge this book by its cover, as a dive into its pages reveals a surprisingly relatable and intriguing peek into the lives of the nobility of Heian era Japan (794-1185). Not quite what you’d expect from “The Pillow Book”, a collection of personal notes written by a lady of the court around the year 1000.

Who Was the Author of The Pillow Book?

Sei Shonagon, which wasn’t her real name but an amalgamation of a nickname and the court position of either her father or one of her husbands, was a lady-in-waiting serving the Empress Teishi in Heian-kyo, now known as Kyoto. The essence of the book is her personal diary, scribbles, observations and essays about the various goings-on in her luxurious, yet tedious day-to-day life. The notes were discovered, read and distributed around the court. It was highly praised and upheld for its literary merit and copies were made to preserve it as the founding work of a new genre of writing.

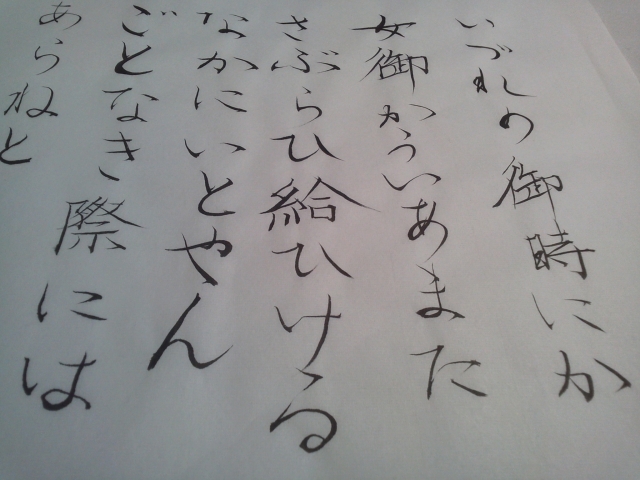

Shonagon’s father was the famous poet Kiyohara no Motosuke, so she likely grew up in a world where words flowed like poetry and she skillfully captured that style in her own work. There are beautiful descriptions of the seasons which one can easily visualize through her carefully crafted words and word plays that create a sense of irony and humor simultaneously.

Read From A Heian-era Blog

Starting with Sei Shonagon, zuihitsu 随筆 became a popular writing style of recording random thoughts, loosely connected ideas and casual fragments of daily observations from the author’s surroundings. Discovering an ancient way of life from Heian Japan can be as easy as scrolling through Twitter, just without the hashtags.

Sei Shonagon actually wrote The Pillow Book around the same time another female writer, Lady Murasaki, wrote the classic “The Tale of Genji”. While that book was polished and glamorized for public consumption, The Pillow Book was its antithesis: raw and honest.

Relate To a Person from 1,000 Years Ago

Sei Shonagon, by Utagawa Kunisada from Ukio-e.org

The Pillow Book is based on writings that were never meant to be seen by the public eye, so Shonagon wrote with an honesty that she could never have expressed out loud or in literature that was meant to be read by others. This gives The Pillow Book its intriguing quality of seeing her world exactly as she saw it.

A praiseworthy quality of Sei Shonagon’s work is its relatability and humour. A large proportion of the notes are lists pertaining to certain categories; for example, ‘Embarrassing Things’ or “Annoying Things”. It’s amusing to be able to connect with an upper-class Japanese lady who lived a thousand years ago on a human level, and finding out that many of the things that make us laugh or cry were the same for her.

An Example of Feminism Centuries Ahead of Its Time

Much of “Western” literature of the time is dominated by male voices, but here is a rare opportunity to hear a female perspective from ‘medieval’ times. Let’s not go overboard; Heian-era Japan was by no means a boon for the feminist movement. The patriarchy was alive and well, as seen from the beautiful yet cumbersome robes which impaired women’s physical movement and the strict limits on education for women, which mainly concerned the arts and other practices where the aim was to enhance their appeal to men. Although this sexism is ingrained in the author herself as revealed in some of her more discriminating passages on female beauty and behaviour along with some minor displays of snobbery, it is nevertheless, her story told in her own words, a rarity for the times.

Sei Shonagon, by Torii Kiyonaga from Ukio-e.org

Overall, The Pillow Book is a cultural history lesson, giving context and perspective to modern-day Japan, with such beautiful imagery as to make you want to travel back in time to the Kyoto of way back when. Sei Shoganon’s skillful writing paints a full image of the intriguing, yet boring life of Japanese nobility from a woman’s perspective. She was reported as saying “I am the sort of person who approves of what others abhor and detests the things they like.”, a true glimpse at her honest and somewhat rebellious spirit that lives on in her work forever.

To experience a little Heian era culture and even the older Asuka era, consider a visit to Kyoto’s Heian Jingu shrine and the nearby city of Asuka in Nara Prefecture, Japan’s oldest capital.

Written by Amy Redihough with additional text and editing by Todd Fong

Great article, thanks for highlighting this great book. Sei Shonagon is sometimes referred to as a “courtesan” (including, regrettably, in the blurb of one edition of The Pillow Book), but she was not a courtesan. She was a court lady, due to her role as a lady in waiting. This might be the source of some confusion. While she did have some famous relationships with men at court, it would be incorrect to call her a courtesan, or high class prostitute. I wonder if you might consider changing that part of the introduction?

I’m sorry to be “that guy”. I just really like Sei Shonagon and her writing and an error like this can detract from her genius literary contributions and is just plain inaccurate. It’s like people who think that geisha are sex workers rather than artists.

Jara, thank you very much for your comment. While we try to do our best to research the facts about our articles, sometimes we get things wrong. We will look into this point and if we can verify it with other sources, we will update it as soon as possible. Would you have any recommended sources for us to look at?

I did a quick check and verified your observation. It is possible our author confused the term “courtesan” with “courtier”. Thanks for pointing it out to us.