Are you flying into Hokkaido (北海道), Japan, from overseas? Then chances are you’ve already spoken your first word of Ainu origin. Hokkaido’s international New Chitose Airport was named after the city of Chitose, which was originally called shikot, meaning big depression or hollow, like Lake Shikotsu in the caldera. It was later changed to Chitose because, in Japanese, shikotsu sounds like “dead bones.”

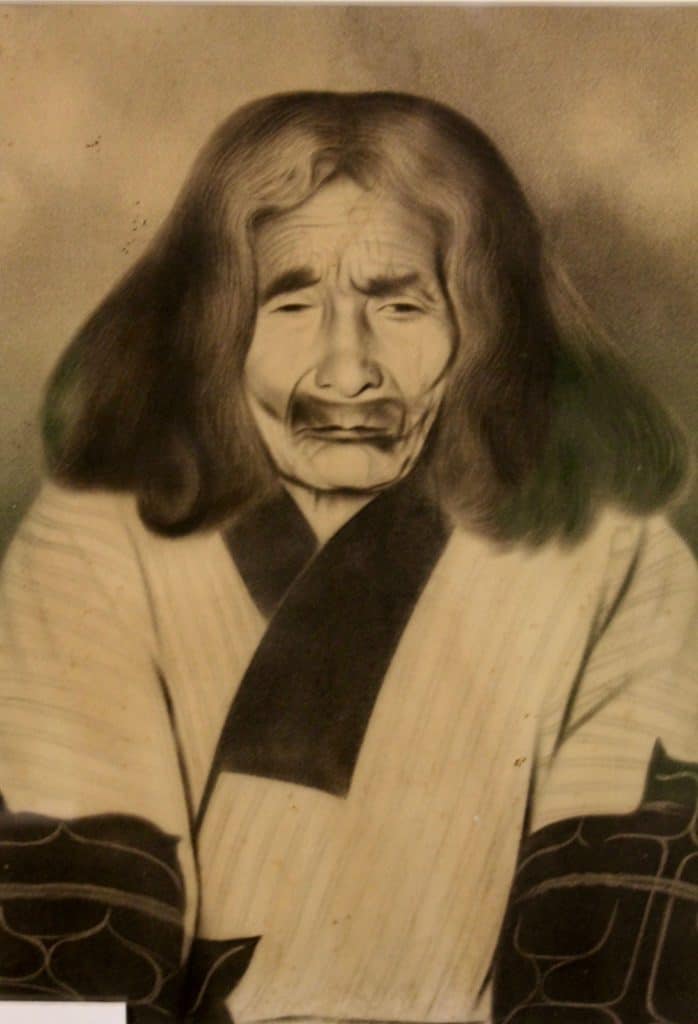

These bones could be those of the many indigenous Ainu (アイヌ) people who lived and died in Hokkaido and other northern islands over the centuries and who passed down their customs and culture through performing arts and oral literature over generations. Although much of these traditions and rituals were lost during Japan’s Meiji period due to discrimination and forced assimilation, new initiatives to revive Ainu culture and history have emerged in recent years.

Who Were the Original Ainu People?

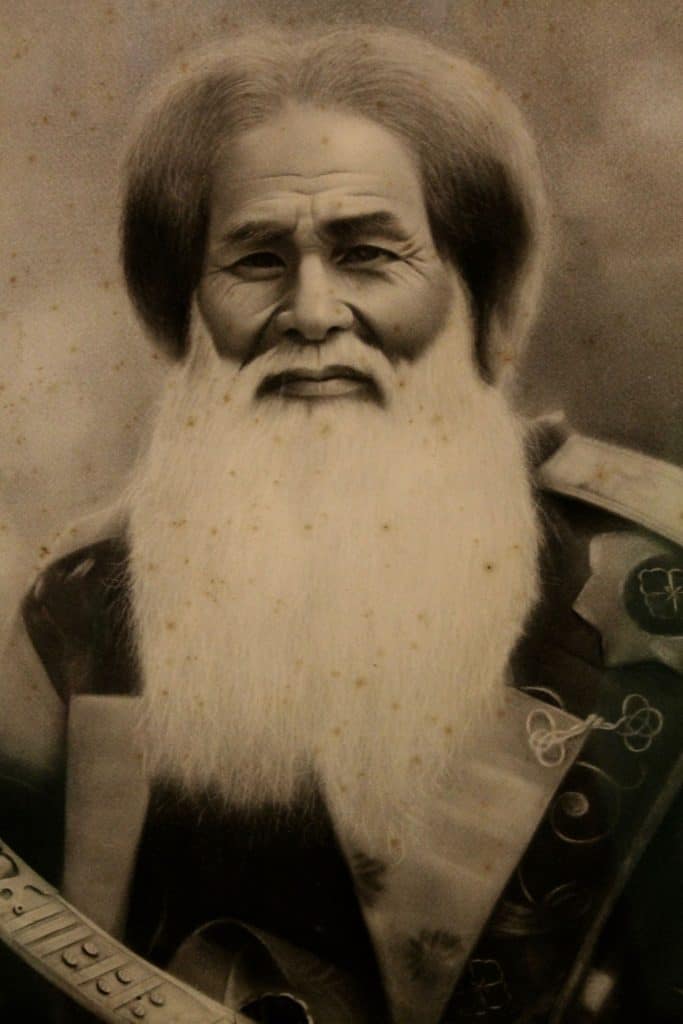

“Ainu” is derived from the native word aynu, which means “human being,” and refers to these indigenous people from the northern region of the Japanese archipelago, particularly in Hokkaido. For centuries, Ainu people hunted bears and deer in the mountains, seals and swordfish in the sea, and salmon in the rivers. They harvested kelp and foraged wild plants such as victory onion in spring, giant lily in summer, and crimson glory vine in autumn. They made clothing from animal furs, fish skins, bird feathers, and fibers from grass and trees. They also traded with other peoples around Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands (also known as the Chishima Islands in Japan) to obtain silk and cotton.

Ainu people’s character stems from their ancient wisdom of living harmoniously with the creatures and natural phenomena in the world around them. Their universe is inhabited by kamuy, spirit-deities who are everywhere in fauna, flora, and the elements, always watching over (if not playfully taunting) humans. For generations, Ainu people told stories in song and dance about human protagonists, legendary heroes, or divine spirits living “between the ears” of animals and interacting with humans.

Unfortunately, radical development and modernization introduced during the Meiji period led to widespread discrimination against the Ainu people and eventually to their forced assimilation into Japanese society. Much of their culture, language, religious rituals, and ways of life – not to mention pride in their identity – was lost during this time and has remained threatened ever since. It wasn’t until 2009 that UNESCO finally recognized Ainu as an endangered language.

The oral language is unique to the Ainu and is totally distinct from Japanese. One way into the language is through the names of geographic places throughout Hokkaido, as well as Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands/Chishima islands , and Japan’s northeastern Tohoku region. For example, words with pet (as in Noboribetsu) or nai (as in Wakkanai) mean “river” in Ainu, suggesting that native speakers have lived in these areas since ancient times. Or consider the names of the lakes: Poroto means “big swamp,” while Akan is derived from the Ainu words rakan pet, which means “river where the dace spawn.” Other words that have been incorporated into Japanese include rakko (sea otter), tonakai (reindeer), and shishamo (smelt, from susuham in Ainu).

Where to Experience Ainu Culture in Japan

While Ainu people have lived throughout Hokkaido, three places in particular are dedicated to preserving Ainu history and reviving their culture and customs directly on their ancestral lands. All are situated in scenic locations of natural beauty, are open to visitors and usually host an annual festival where you can see ancient rituals, torch parades and traditional dances.

Upopoy in Shiraoi, Where Ainu Spirits Sing

For a more practical introduction to the Ainu language and history, head to the south of Hokkaido on the scenic southern end of Lake Poroto in Shiraoi (about an hour by express train from Sapporo or 40 minutes from New Chitose Airport). There you’ll find Upopoy (ウポポイ), a place that is dedicated to revitalizing Ainu culture. Upopoy means “singing together in a large group” in the Ainu language, and the expansive site has been officially designated as the “symbolic space for ethnic harmony” by the Foundation for Ainu Culture. This is also where you can learn to say “hello” (“Irankarapte!”) and other popular Ainu greetings.

Upopoy is home to the National Ainu Museum, which relays the torch from the original Ainu Museum in Shiraoi which was founded and operated by the Ainu people for over 30 years until 2018. Since July 2020, the new national museum has preserved its extensive collection of historical artifacts through thematic exhibits and performing arts. The exhibits explore Ainu history and culture from an Ainu perspective, with Ainu-language explanatory panels written by people from a diverse range of linguistic heritages based in different areas.

The museum is situated within Upopoy Park, which includes a traditional Ainu village (kotan), performance hall, workshop, and crafts studio where you can practice hands-on activities. On-site eateries serve traditional dishes and Ainu fusion cuisine.

Also living inside the park, alongside various wildflowers, are more than 40 species of trees with culinary, medicinal, ceremonial, and practical connections to Ainu culture. In winter, you can see Sakhalin fir, whose sticky resin the Ainu used for adhesive and thick branches to build tepee-like huts, with the inner bark of Japanese lime used as rope. Dogwood was used to craft inau, typical ceremonial offerings to the kamuy spirit-deities. The fruit of the soft Amur cork tree was simmered until it became hard enough to be sucked as a medicinal lozenge. Soft Manchurian elm fibers were woven into garments.

Ainu Arts, Crafts, and Culture by Lake Akan

In the hot spring mountains of eastern Hokkaido, on the southern end of Lake Akan (阿寒湖, Akanko), the Akanko Ainu Kotan settlement is inhabited by about 120 people in 36 residences. It’s another dedicated place in Hokkaido to learn about traditional Ainu lifestyles and see ancient ceremonial dances, puppet shows, or oral history performances. Here you can also watch the local artisans at work and even try your own hand at Ainu arts and crafts.

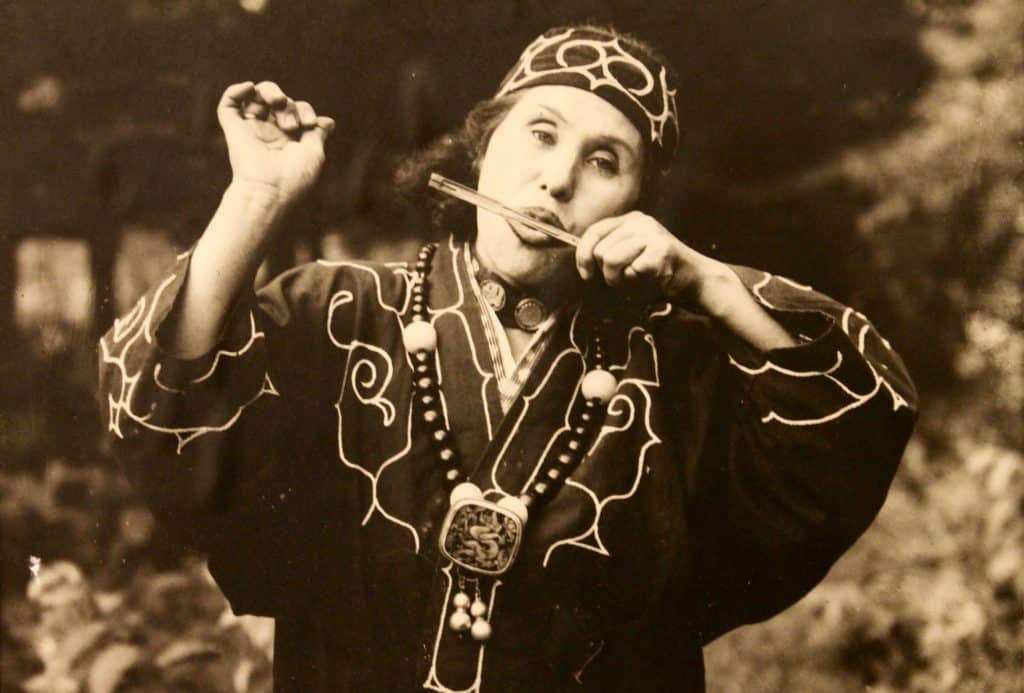

Ainu are traditionally skilled in woodcarving, and one of their most popular woodcrafts is the mukkuri. This bamboo mouth harp is shaped like a long thin plate, with the center carved out for the tongue and a string attached to both ends. The musical instrument’s rich expression ranges from human sighs to sounds of nature such as raindrops, bear cub cries, or blowing wind.

Ainu ceremonial clothing is often decorated with unique patterns, made through cutouts and embroidery, such as moreu (spirals) and aiushi (thorns). The patterns are often different across regions, passed on from mother to daughter, and were first developed to ward off evil spirits. Akanko Ainu Kotan displays a wide range of patterns that you can see close-up, and the local craftswomen can show you how to embroider your own coaster to take back home.

Marimo Festival of Green Algae Balls

Symbolic of the Ainu people’s ancestral lands, Lake Akan in Hokkaido is also famous for its giant algae balls known as marimo (毬藻). Marimo are a rare spherical growth of filamentous green algae resulting from the gentle oscillations of shallow lake waters. With a growth rate of 5 millimeters per year, only in Lake Akan have marimo been found to grow up to 30 centimeters in diameter. These marimo have been designated a special natural treasure in Japan, and Lake Akan is protected as their native habitat.

The Ainu have known about the natural phenomenon of green algae balls for centuries and treasure them as part of their natural heritage. To join in the marimo celebrations and catch an evening torch parade with traditional dances in full costume, come to Lake Akan during its annual three-day Marimo Festival on October 8-10, held since 1950.

Kamikawa Ainu in the Mountainous Playground of the Gods

For a more geographically immersive experience, travel to the western foothills of the Daisetsuzan (大雪山) mountain range, where Kamikawa Ainu (上川アイヌ) have lived harmoniously with kamuy since ancient times. They believe that when spirit-deities descend into the realm of humans (Ainu mosir), they appear in the forms of mountains, rivers, animals, plants, and other natural manifestations.

Kamikawa Ainu venerated the formidable Daisetsuzan mountain range as the “playground of the gods” (kamuy mintar). Its topography features unusually shaped boulder stacks, sheer riverside cliffs, columnar joints, multilevel waterfalls, and raging torrents. These mountains also provide a habitat for unique native alpine flora and fauna, including the endemic yellow-speckled Usubakicho butterfly and Miyabe char subspecies of Dolly Varden trout.

In the Ishikari river basin, Kamikawa Ainu built traditional dwellings (cise) thatched with dwarf bamboo and prospered on trade. About 10 kilometers upstream, Mount Arashiyama (Cinomisir, “our prayer mountain”) is a sacred place where some traditional Ainu ceremonies are still performed today, including their most formal ritual of sending the spirits of Blakiston’s fish owls back to the realm of the gods (kamuy mosir).

In the city of Asahikawa (旭川), you can learn more about the history and culture of Kamikawa Ainu at the Asahikawa City Museum and especially the dedicated Kawamura Kaneto Aynu Memorial Museum. In 2018, a total of 21 cultural properties in the area around Daisetsuzan were collectively designated a Japan Heritage Site, and all the local municipalities welcome visitors to come and explore the natural and cultural heritage of Kamikawa Ainu.

Ancestral Chants of Lively Legends

I still remember my initial delight in discovering “The Song The Fox Sang” – towa towa to – a lively Ainu chant about a hapless fox who mistakenly sees dramatic situations centered around humans in what are, in fact, everyday scenes of nature. I love how this humorous oral legend evokes ritual cries and gestures and humans’ intricately rooted relationship with divine spirits and the natural environment.

“The Song The Fox Sang” is one of the 13 oral chants recorded and translated into Japanese by the young Ainu woman Chiri Yukie (知里 幸恵), who learned the chants from her aunt and grandmother. Unfortunately, she died of heart disease at age 19, just before her seminal Ainu Shinyoshu (アイヌ神謡集), a collection of kamuy yukar (epic tales chanted in the first person by spirits, animals, or personified natural forces), was published in 1923. This book was the first printed record of Ainu oral literature written by the Ainu themselves. Today, the Chiri Yukie Memorial Museum, located not far from Upopoy, exhibits artifacts and documents from the young author’s life and work. Yukie’s younger brother Chiri Mashiho (知里 真志保), was also a linguist and anthropologist, best known for his Ainu-Japanese dictionaries and colloquial Japanese translations of oral Ainu folklore.

Exactly one hundred years later, Chiri Yukie’s endeavor is symbolic of the plight of surviving Ainu culture today. As so many aspects of the people’s traditional lifestyles are no longer possible, Ainu language and oral literature have become the most authentic insights into their perspectives on life and the universe. Traveling to Hokkaido to experience their heritage, culture, and performing arts in person from descendants themselves is just one way we can help ensure that Ainu culture lives on, both in Japan and beyond.

No Comments yet!