No doubt, the most striking piece of artwork inside the National Theatre of Japan in Tokyo is the Kagamijishi (鏡獅子), a life-size statue of the lion spirit that dances vigorously among the spring blossoms. Even frozen in a dramatic pose, its long white mane seems to whip through the air and spill over its shimmering golden robe. The statue was modeled after stage performances in 1936 by the kabuki actor Onoe Kikugoro VI, which the artist Hirakushi Denchu watched a total of 25 times, each time from a different angle, before finally completing the present statue more than 20 years later.

Such is the power of kabuki (歌舞伎), this Edo-period form of lavishly costumed, highly stylized lively performance that has captivated fans for centuries. In 1966, the Kagamijishi arrived at its new home in the lobby to inaugurate the official opening of the National Theatre of Japan in Tokyo. Still today, this iconic art piece symbolizes the undying energy of traditional Japanese performing arts, which are continuously staged, lovingly nurtured, and dutifully archived year-round by the Japan Arts Council.

Classic Medley of “Onnagata” Kabuki Dances

On the last Sunday afternoon of February, the National Theatre rustled with excitement before a special performance titled “Moon, Snow and Flowers – Performing Arts Celebrating the Natural Beauty of Japan” (月・雪・花-四季折々のこころ-). Intended for all audiences, this foreigner-friendly medley of famous kabuki dances and traditional Japanese instruments was part of the ongoing Japan Cultural Expo program that had originally been planned to coincide with the Tokyo 2020 Olympics.

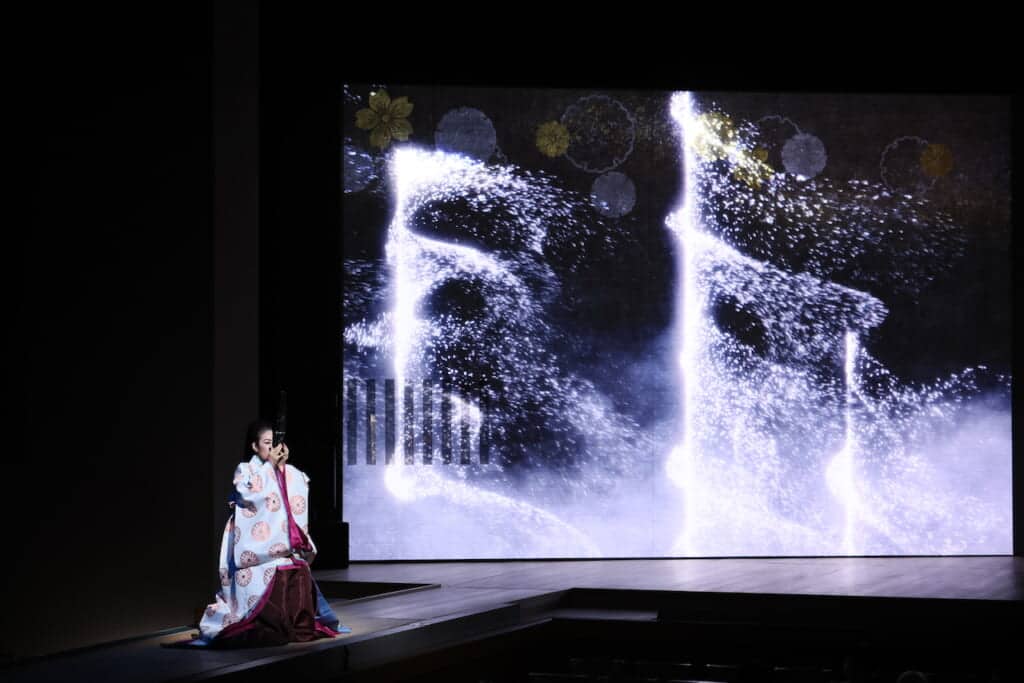

No time was wasted with wordy introductions—as soon as the curtain was raised, the stage was set. Each season of the musical trilogy began with a spectacular dance solo from the kabuki repertoire performed by the famous actor Onoe Kikunosuke, who specializes in onnagata (女方) female roles: the lunar maiden wearing a celestial feathered robe in the Noh-inspired “Hagoromo” (羽衣); the lovelorn snow-white egret who emerges from an instant hikinuki (引き抜き) thread-pulling costume change in “Sagi Musume” (鷺娘); the temple dancer longing to be free from earthly suffering amidst a flurry of cherry blossoms in the great classic “Musume Dojoji” (娘道成寺).

Kabuki “Hagoromo,” starring Onoe Kikunosuke, a National Theatre production | Photo courtesy of Japan Arts Council

Kabuki “Sagi Musume,” starring Onoe Kikunosuke, a National Theatre production | Photo courtesy of Japan Arts Council

With their elaborate costumes and stylized gestures, the visual appeal of these dances was irresistible, even without knowing the stories behind them. There were also quite a few experienced fans in the audience who applauded both in anticipation and in appreciation of classic kabuki highlights. For the rest of us, it was a rare opportunity to see and hear a live kabuki stage performance, complete with the musical accompaniment of narrative nagauta (長唄) and minimalist hayashi (囃子) ensemble of hand drums and flute. By that time, I was already entranced by the distinctive sounds of wagakki (和楽器), Japanese traditional instruments.

Songs and Storytelling with Japan’s Traditional Musical Instruments

The popular shamisen (三味線)—featuring three silk strings strummed over stretched animal skin—is highly charismatic, not least because of its musical agility when accompanying vocals and drama. At the National Theatre, it was brought to life not only in nagauta, but also in a traditional shinnai (新内) recitation about a love suicide, as well as in a mesmerizing sokyoku (箏曲) performance with bamboo flute and featuring the elegant zither-like koto (箏), about a samurai who burns his precious bonsai as firewood to warm a traveler on a snowy day.

When it comes to epic storytelling, nothing beats the biwa (琵琶), a deeply resounding short-necked lute that came to Japan in the 7th century through the Silk Road. It is often associated with Japanese Buddhism and was famously played by blind monks reciting the Tale of the Heike (平家物語) in the Kamakura period (1185–1333). In the Flower part of Sunday’s concert, Shuto Kumiko gave a dramatic performance of “Haru no Utage” (春の宴, spring banquet), a composition based on the written Tale of Genji (源氏物語). Shuto was one of several soloist musicians who were graciously spotlighted on the kabuki stage-specific hanamichi (花道) elevated walkway through the audience, mystically rising and sinking on the suppon (鼈) trap door lift.

Another solo performance that was dramatically enhanced by the theater itself was by the sho (笙) player Tono Tamami. She, too, was physically elevated into the spotlight, which illuminated her billowy robe as she played the free reed instrument characteristic of gagaku (雅楽) imperial court music of the Heian period (794-1185). But while the exquisite sho can often sound like an extremely delicate harmonica, as amplified through the auditorium speakers, it resounded like a luxuriously ethereal pipe organ.

Spiritual Buddhist Chants and Suave Bamboo Flutes

One more rare highlight of the concert was shomyo (声明), a style of Japanese Buddhist chant performed by the research and promotion group Tendaishomyo Shichisekai. All the monks stood in a single row across the stage to form a harmonious panoramic instrument. Like gagaku, shomyo uses the Japanese pentatonic Yo musical scale, giving the chants an otherworldly uplifting aura.

Meanwhile, Japan’s timeless bamboo flutes have survived and revived many musical genres across the eras, all the way into modern-day live houses. At the National Theatre, I was just as moved by Fukuhara Toru’s moonlit performance of “Kyo no Yoru” (京の夜, Night in Kyoto) on the transversal shinobue (篠笛). And I shivered upon hearing the unmistakable wail of Tanabe Shozan’s vertical shakuhachi (尺八), which is also used for Zen meditation, in a solo piece representing the lonely sound of the wind blowing through bare winter trees after an earthquake… circling back to the sound of primordial human breath blowing through a single bamboo reed.

Shinobue, a National Theatre production | Photo courtesy of Japan Arts Council

Shakuhachi, a National Theatre production | Photo courtesy of Japan Arts Council

It’s also thanks to kabuki that the classical repertoire of the medieval nohkan (能管) grew well beyond its original roots in 14th-century Japanese noh (能) theater. Some may call it an acquired taste, but more recently, the signature high-pitched whistle and uncanny whine of this singular flute, rising above percussive beats and strums to herald the artful kabuki dance, have grown on me too.

See Japanese Traditional Performing Arts in the Imperial Gardens of Tokyo

After this very pleasurable kabuki medley staged at the National Theatre, the Japan Cultural Expo program continues on March 12–14, 2021. For the first time, outdoor performances of “Representation of Prayer” will feature nohgaku (能楽) and other Japanese traditional performing arts staged inside the Kokyo Gaien National Garden in Tokyo, with the Imperial Palace’s iconic Nijubashi Bridge in the background. Tickets are on sale now, for either on-site attendance (¥1,400 – ¥4,000) or online video streaming (available from March 12-30, ¥1,200).

No Comments yet!