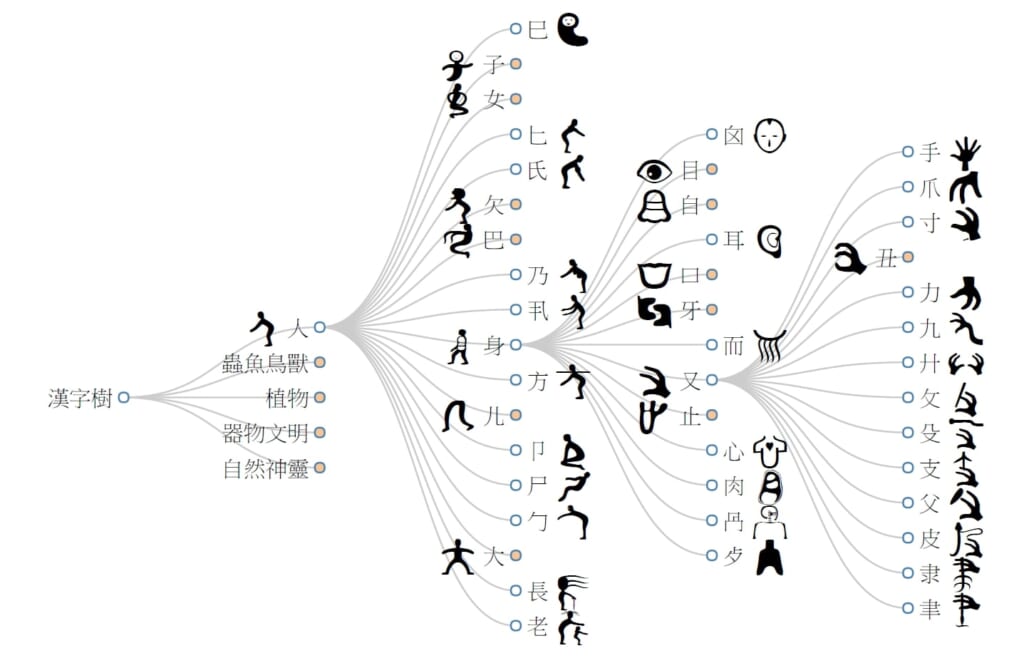

Kanji. The bane of students of Japanese, of certain carefree T-shirt designers and tattoo artists victims of customers lacking enough mastery of the language. The aesthetic fascination for Chinese ideograms lies at the core of countless stories of misunderstandings, student drama, and endless arguments to define the best learning techniques. Nowadays, several may wonder why people still use kanji instead of phonetic writing, such as the Roman alphabet. The answer is because of various cultural and historical factors.

Are Kanji and Chinese Characters the Same Thing?

Yes and no. The Japanese language is nothing like the Chinese in terms of speech. But its writing system uses the same characters originated in China since it was believed that there was originally no written language in Japan before this time. Essentially, they are the same characters. But there are some nuances. Since their introduction in Japan, both countries have carried out reforms and simplifications separately and for different reasons. As a result, there are divergences in the meaning or writing of some characters. There are cases in which common kanji in Japan may be obsolete in China since the latter carried out a deeper reform. Therefore, although the level of intelligibility between both languages indeed remains, in terms of reading, this only means that Chinese people and Japanese people can understand the meaning of a text in broad terms, but not in the same way as each other.

Is Kanji Really That Difficult?

Here are some of the most common misconceptions:

Misconception 1: There Are Too Many Kanji

For those beginning their studies, the thought of thousands of kanjis can be overwhelming. Actually, the 500 most frequent kanji already cover 80% of the characters that appear in one of the main Japanese newspapers. However, this is not the same as saying that one only needs to learn 500 “words” to master the language. Much of the Japanese vocabulary consists of combinations of two or more kanji whose meaning is not necessarily obvious from each kanji’s individual meaning. As a reference, the official list of regularly used kanji has 2136 characters in its last update in 2010.

Misconception 2: Kanji Increases the Reading Difficulty

On the contrary: reading in Kanji is faster. Because of the high number of homonyms in Japanese, a purely phonetic text would be difficult to understand. Ideogram recognition is immediate due to its visual component.

Misconception 3: The Meaning of A Kanji Can Be Deduced If Its Components Are Known

This is a small trap that some may fall into. Sometimes it can work but the meaning is not always obvious. For example, the kanji 力 (strength) often appears in concepts related to physical action or effort: help, 助 (目 eye + 力); move, 動 (重 weight + 力) or effect/result 効 (交 mix + 力). The individual concept can help you to memorize it afterward, but beforehand, the meaning doesn’t have to be intuitively evident.

Misconception 4: Repeated Writing is the Only Way to Learn

Although writing over and over again is a very effective method, that doesn’t mean there are no other learning strategies. Many traditional schools are responsible for maintaining this idea, in part because it’s a relatively easy concept to grasp and follow and because it’s the method that Japanese children normally use in school. But generally speaking, Japanese language students can benefit from combining various techniques such as morphological analysis, reading in context, or the use of mnemonics. Technology today also provides multiple additional means for language study.

When Kanji Was About to be Abolished

Surprising as it may seem, kanji actually came dangerously close to being uprooted, just like it happened in South Korea or Vietnam. Since the Meiji Era (明治時代, Meiji jidai), many voices of reformist intellectuals insisted that Kanji’s use was detrimental to the modernization of the country and its integration with the West. One of the main problems had to do with the difficulty of making efficient use of printing technology. Telegrams and Morse code were equally problematic because of the number of homonyms in the language. For this reason, after the end of World War II, the Occupation Government planned a series of measures aimed at language reform, including the elimination of Japanese characters and the implementation of the Roman alphabet.

They held the belief that Kanji was an educational problem. Therefore, they conducted and a nationwide survey to check the literacy levels of the population. Against all odds, the results left no room for doubt: 98% of respondents were literate. We can establish this key moment in history to answer why Japanese people still use Kanji today.

Will Kanji Ever Disappear?

Very unlikely. In the last few decades, modern technology has been the greatest ally of kanji usage. Technical problems related to the use of kanji disappeared with the advent of modern word processors. Even some less common kanji have been added to the list of commonly used kanji because of this. Similarly, the regular use of instant messaging has reinforced the same trend, though it came with a cost. Many Japanese people now find it difficult to write by hand the more complex kanji due to lack of habit. In any case, the hopes of some struggling students are far from being fulfilled. The use of kanji is in excellent health nowadays, and no risk of the opposite is in sight.

No Comments yet!