New Years, known as Oshōgatsu (お正月), is possibly the biggest national holiday in Japan. For comparison, it’s similar to Christmas or Thanksgiving in Western cultures where families near and far gather together and feast. There are many deeply rooted traditions that come with welcoming the new year, and while specifics may vary from region to region, and family to family, below are some of the Japanese New Year traditions that are widely practiced.

Decoration:

The preparation begins days before the big gathering on January 1st. It begins with the decorations on December 29th or 30th because a one night decoration on the 31st, ichiyakazari (一夜飾り), is said to be a bad sign of laziness or putting things off until the last minute. For these said decorations, there’s the pine, kadomatsu (門松), to put up by the front entrance and an elaborate mochi, kagamimochi (鏡もち) , in the living room. In my family’s tradition, many relatives begin to gather at my grandparents’ house on New Year’s Eve, ōmisoka (大晦日) . The eve is already the beginning for some feasting; we eat the year-crossing noodle, toshikoshi soba (年越しそば), which is simple and garnished with citrus yuzu. Then to fix the sweet-tooth craving, there’s red bean soup, oshiruko (お汁粉), with mochi in it.

Countdown:

Some younger crowds choose to go out to party for the countdown, but there are also many alternative ways to enjoy the evening, both inside and outside of the house. New Years is in the dead of winter so of course, many choose to stay indoors. There are a few beloved TV shows on for the eve. The most traditional and famous one is NHK’s Kōhaku Utagassen (紅白歌合戦) which is the year-end song festival. For the show, Japan’s famous musicians of all decades and genre are grouped into red team for female groups and vocalists and white team for male groups and vocalists. Musicians perform and entertain all evening leading up to the new year, and then reveal one team as the winning team. Some other popular shows for the evening include stand-up comedy, owarai (お笑い) and Beethoven’s philharmonic symphony.

Shrine or Temple visit:

There is also a colder, more spiritual way to spend the evening outside. Crowds of people gather at nearby temples to hear the joya no kane (除夜の鐘), the New Year’s Eve bell, ring more than a hundred times. The ringing signals the end of the previous year, and beginning of the new, with each ring representing the desires humans experience over a lifetime. Being at a temple or shrine at this time is also a chance for the earliest hours of hatsumōde (初詣). Hatsumōde marks the first visit to a shrine or temple for the new year. Many religious and spiritual sights are packed for the first three days of the year with people flocking to wish for the year’s good luck. If you’re in the Tokyo area, Meiji Jingu in Harajuku is the most trafficked hatsumōde spot with special Yamanote train platforms created just for this time of the year. Dare to go if you’re ready to experience a packed new year tradition…or if you’re one to avoid crowds (like myself), trot over to your neighborhood shrine or temple for a peaceful prayer.

The Greeting:

No matter where you are when the clock strikes midnight, remember to say “Akemashite Omedetou!” Its literal translation means “congratulations for opening (the new year),” but of course, it means Happy New Year. The younger generation of Japanese folks also like to shorten the greeting to ake ome (あけおめ)! Either versions of the sayings are used to greet family and friends for the first dew days of the year. However, there is one circumstance in which saying Happy New Year to someone could be inappropriate; that is if they have had a death in the family during the year leading up to the new one. Many rarely will take offense if this rule is broken, but it’s still a good one to remember.

New Year’s Day Meal:

On New Year’s Day, the often quiet house comes to life with nostalgic laughter, swift cutting of the vegetables, and the aroma of warm fish broth. Elder cousins and uncles catch up over drinks while the young entertain the younger with a game of sugoroku (双六) or some tender teasing. Amazake (甘酒), sweet non-alcoholic rice saké, is passed around to satisfy rumbling stomachs while everyone awaits the feast. There are many dishes that are unique to the New Year’s feast that aren’t commonly enjoyed at other times of the year. This special New Year’s cooking is called osechi ryōri (おせち料理). Below are some of these dishes and their significance:

kamaboko (蒲鉾)- broiled fish cake in pink and white to represent the celebratory colors, red and white.

daté-maki (伊達巻) – sweet egg rolls with fish paste to represent good weather for the days to come.

kurikinton (栗きんとん) – mashed sweet potatoes and chestnuts to represent wealth.

konbu-maki (昆布巻き) – kelp rolls to represent joy, as it’s a play on word from yorokobu.

Kazunoko (数の子) – herring roe to represent fertility.

kuromame & chōrogi (黒豆とチョロギ) – black means and Japanese artichoke because the word for beans, mame also means health.

sudako (酢だこ) – octopus soaked in vinegar.

namasu (なます) – vegetables soaked in sweet vinegar.

In addition, there is also shrimp for longevity (shrimp’s image with long beard and bent waist), red sea-bream fish for celebration, and sushi. In our family, we also order pizza for a change in taste (hey, every family is different!).

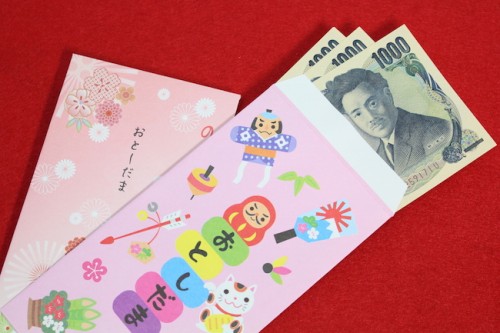

Money as Gift:

The feast is not the only exciting part of the day – there’s giving and receiving of money involved too! Adults give children money as allowance for the year (nowadays, it sure doesn’t last a whole year). This is called otoshidama (お年玉) which directly translates to “the year’s coins.” Generally, children in the family continue receiving this until they are employed, at which point they must start giving otoshidama to the younger family members. The amount varies between families and age. The otoshidama is given in special otoshidama envelopes with cute designs on them like Disney characters or the year’s zodiac animal.

Surprise Shopping:

With bellies and wallets both full, there are two remaining missions at task for the New Year’s holiday: sleeping and shopping. The days following January 1st tend to be the biggest bargain days in Japan. Sure, it might not get quite as crazy as Black Friday in the United States but shoppers still go nuts here. What everyone has their eyes on are the “lucky bags” called fukubukuro (福袋). Many brand name stores will provide limited amounts, while other stores may have a few hundred at hand. These bags have multiple items inside, but are sealed so that you can only find out what’s inside once you buy the bag. Fukubukuro can range from a few hundred yen at jewelry or knick knack stores to tens of thousands of yen at brand-name stores. Some are even sold at food shops. These lucky bags are a good way to see what the luck has in store for you, or just a fun shopping experience to start the year off right!

New Years is a family holiday event. If you have Japanese friends or staying with a host family, hopefully you’ll get a chance to experience it for yourself. Don’t forget to always bring an omiyage gift for the family who invites you!