Sponsored by Cabinet Office, Government of Japan “The Cool Japan Public-Private Partnership Platform Project”

Visit Sake Brewery in Obuse Town

In the pretty little town of Obuse (see the previous article on Obuse), we had the chance to visit one of the most prestigious manufacturers of nihonshu (Japanese alcohol: sake) in Obuse town, Nagano prefecture: Masuichi Ichimura Sake Brewery.

Established in 1755, Masuichi Ichimura Sake Brewery is unique in so many ways. First of all, they make sake modern-looking. Several sake products are sold in very original bottles (the bottles are sometimes made of steel; sometimes with logos rather than the traditional kanjis; sometimes with capsules similar to beers). On the other hand, the company only sells on site (or online). It is impossible to find their products in the shops of the rest of the country, and the reason is very simple: the owner wants to meet his customers and let them see where the sake come from, and how it is made. To see the obvious commercial success of this brewery, it must be believed that this method worked.

The owner of the brewery (and also the connected hotel and restaurant), Mr. Tsugio Ichimura, explained that no matter what bottles are used, or how remarkably modern the names and labels are, he wants to promote a traditional manufacture: “I wanted to go back to basics of sake, use old methods of production,” he mentioned. Let us check that out!

A Reputation from the Great Hokusai

For the small (or big?) story, the brewery got its great reputation much in part by one of Japan’s most famous painters, Hokusai. Having spent part of his life in Obuse, in late 1845, Hokusai introduced this excellent sake and the links that united it to the producers.

Visiting the breweries, you can feel how the Masuichi team worked very hard for a long time. “We have been using the same factories for over three hundred years,” said Tsugio Ichimura.

The Preparation of a Daiginjo

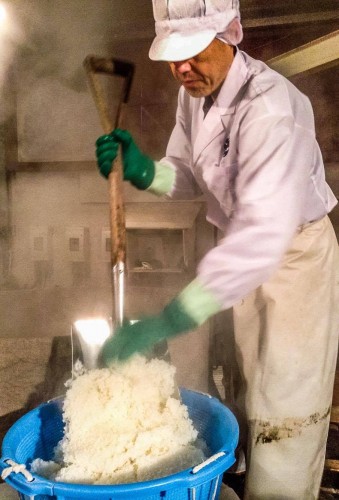

We began our tour by visiting the place where the rice is steamed. This first step is to prepare the ingredients properly. The rice is sterilized and polished, modifying its chemical structure. It should be noted that we have witnessed the preparation of a daiginjo, which is probably the most prestigious kind of sake. In this process, when the grains of rice are polished and their skin is removed at a rate exceeding 50%, its taste becomes more refined because one reaches the heart of the grain, which is rich in starch. Fermentation is carried out at a low temperature which is not only more delicate, but also requires more time.

When we visited there, it was in the beginning of February. This is the end of the season for sake production, since there are fewer bacteria this season and the drink is more sensitive.

Sake is made with water with rice and koji (see below), three essential elements of the process. Koji is perhaps even the most important because in the end, the sake will be composed of more than 80% of water! No wonder the manufacturers give it such importance and respect.

100% Pure Local Rice Produced in Nagano

The rice used here comes 100% from the prefecture of Nagano. Today, a gas appliance is used to heat the basin. During our visit, the basin contained 200 kilograms of rice (though it can contain up to 400 kilograms, depending on the type of sake produced). Steaming is somewhat uneven, and thus, the rice at the bottom of the reservoir is more cooked than the rice on the surface. If the first batch is then placed in the tanks to begin the fermentation process, the second will be used for the next phase, called the preparation of the koji (as will be explained later).

A Kind of Sauna

The person responsible for fermentation has a very important role to play. His experience tells him when the rice is ready, when the moisture is satisfactory. Once ready, the rice is fed, shoved in baskets, and brought into a special wooden room that is heated to 35 degrees with a moisture content of 80%. This room reminded me of a sauna.

There are other techniques to cool rice, but the company Masuichi favors this one: they do it manually because that is the most traditional way.

“This step is very important and one of the most difficult for us, the workers, because it is very hot and requires strength and concentration,” says Naomichi Ichikawa, who has been working there for 25 years.

Produce Koji

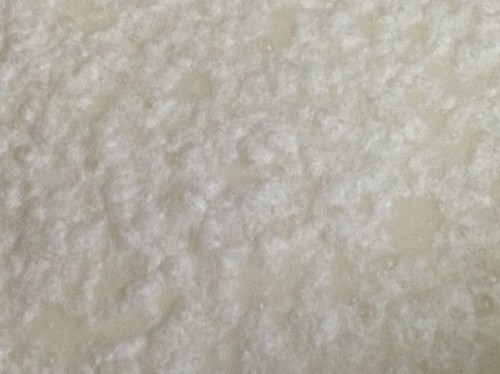

It is in this room, once the rice is brought inside, that the koji grows. To make it simple, the koji is a kind of tiny fungus and that will make it possible to transform the complex sugars into simple sugars. Without koji, no fermentation and therefore no sake! The koji is a kind of powder, placed in a small sieve and sprinkled on the rice which had previously been spread on large tables. It is in this room that, for 48 hours, the koji begins its action on the rice.

Place to Ferment

Clearly, the production of koji represents the first (and most difficult) of the three phases of sake fermentation. The second is called shubo and corresponds to the beginning of the fermentation itself. It is at this time that the koji is mixed with water, rice and yeast.

“For daiginjo sake, it is left to macerate for two weeks,” explains Mr. Ichikawa, explaining why it is important to take the time. “Low temperature fermentation is an essential technique so as not to break rice too roughly, which would create too much taste, too many acids and too much alcohol content.”

In the next stage, called moromi, the sake is transformed into larger tanks. It will stay there for a month until it reaches a 12-degree alcohol level.

The tanks used in the Masuichi Ichimura Sake Brewery contain 2,200 liters, which were produced from only 600 kilos of initial rice.

During our visit, three employees worked in the brewery under the supervision of the toji, the master brewer. The toji’s role is essential and is greatly respected. In the photo below, the toji (second from the left) is with other employees of the Masuichi brewery.

Once moved from the vats, the sake will go through several stages before being put on sale: pressing, filtering and then ripening for about six months before bottling. Kanpai!

Original article by : Aurélien Hubleur

Translated by: Rebecca Aptaker, Aika Ikeda

[cft format=0]

No Comments yet!