For well over a thousand years, the Japanese have been making ascetic and symbolic pilgrimages along the mountainous trails of the Kumano Kodo (熊野古道). To hike the Kumano Kodo is to embark on one of Japan’s most ancient spiritual journeys, through an undulating expanse of primeval nature steeped in mist and mystery, in folklore and legend; to walk in the land of the gods.

The trails take their collective name from the Kumano region of Wakayama Prefecture, which covers the southern part of the Kii Peninsula in central Japan, and the Japanese word kodo, meaning “old ways.” The Kumano Kodo is also the only walking trail, besides the Camino de Santiago in Spain, to be designated a UNESCO World Heritage Cultural Landscape. Its principal attractions are the Kumano Sanzan, a group of three grand Kumano shrines and one temple — Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine, Kumano Nachi Taisha Grand Shrine and its adjacent Nachisan Seiganto-ji Temple, and Kumano Hayatama Taisha Grand Shrine — where the kami, or Shinto gods are said to reside.

As someone with a penchant for hiking, an interest in Japanese history, and a soft spot for ancient polytheistic belief systems (in which the roots of Shintoism are planted), I was charged with excitement at the prospect of walking the Kumano Kodo. Luckily, I found myself in a car snaking alongside the Kumano-gawa River in late December en route to the pilgrimage trail.

Entry into the Kumano Kodo: the Land of the Gods

Unloading from the car at a small shrine complex — which I’d later learn was Takijiri-Oji; the Kumano Kodo mountain pass entrance — I met up with my Colorado-born guide, Mike, who’s lived in Wakayama’s Tanabe City for over 20 years. An adopted local, his knowledge of the trail was encyclopedic. Plus, he walked with a stick, and I tend to put trust in people who walk purposefully with sticks.

I was hoping we could cover a significant portion of the trail in one day before Mike informed me it covers hundreds of miles and takes various routes in and around the Kii Mountain Range. I reigned in my somewhat lofty ambitions and accepted that walking as much of the Kodo as we could pack into one day would suffice.

There are six main walkable trails (Kiiji, Kohechi, Nakahechi, Ohechi, Iseji, and Omine Okugake-michi) making up the Kumano Kodo pilgrimage, which connect the three grand shrines and temple, as well as providing routes to Koyasan (the mountaintop home of Shingon Buddhism), Yoshino (a significant site of mountain worship in Nara Prefecture), and Ise Jingu in Mie Prefecture (Japan’s most important Shinto shrine).

The Kodo trails come in varying levels of difficulty, while some have been preserved better than others. The Nakahechi route is the most popular, covering fairly manageable terrain for 30 km between the Tanabe outskirts and Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine. The Kohechi and Omine Okugake-michi are complex and undulating treks through steep forests, flanked by few inns and rest stops; they are not recommended to be taken without trained guides and thorough preparation. The two coastal trails, Ohechi and Iseji, around southern Wakayama and toward Ise Jingu respectively, have largely succumbed to construction given their proximity to civilization, but have retained some remnants of their former glory.

The Great Diarists and History of the Kumano Kodo

The Nakahechi route was our entry point to the Kumano Kodo. We kicked things off at the adjacent Kumano Kodokan information center, a dodecagonal wooden hut nestled on the banks of a trickling river surrounded by evergreen forests. Here I learned of the trails’ historical context, who began walking them, and why.

Historically, mountains in Japan were considered both the abode of the gods and a gathering space for the spirits of the dead. For this reason, the mountainous Kumano region was always revered by adherents to Japan’s polytheistic belief systems (which were to become collectively known as Shintoism).

After the Chinese brought Buddhism to Japan between the 4th and 6th centuries, it gave structure and organization to Japan’s indigenous religion. The two religions syncretized to form one larger school of thought, where Buddhism and Shintoism worked in tandem; local Shinto kami were now, in essence, manifestations of Buddhist entities.

In the Heian Period (794 – 1185) the act of pilgrimage was largely reserved for the religious and political elite. And it was the elite’s connection to the intertwining philosophies of Shintoism and Buddhism that led to the Kumano Kodo’s beginning as a pilgrimage.

South has always been an auspicious direction; the Kodo was directly south from Kyoto (the former capital and home to the Heian Courts). The Kumano region is also home to Japan’s creation mythology; namely, through the first emperor Jimmu — a supposed descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu — who spent time navigating the testing Kumano terrain en route to founding Japan. The Buddhist deities worshipped in Kumano were also linked to their own cosmic paradises; ascending the trails to honor them in Kumano — a literal paradise on earth — was also considered a pathway to achieving internal paradise. Furthermore, the Kodo was an ideal outlet for ascetic practices, as well as for purification of the mind, body, and soul.

Thanks to the poets, scribes, and scholars who walked the Kumano Kodo alongside the aristocracy, there are first-person accounts of pilgrimages from the Heian Period — replicas of their diaries sit in glass cases within the information center.

It’s from these first-hand pilgrimage diaries, such as Chuyuki (中右記) by Heian noble Fujiwara-no-Munetada (1062–1141), that we can learn about the journeys themselves. After visiting Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine along with a retinue of travelers, Munetada arrived in Yunomine Onsen, still thought to be the home to one of Japan’s oldest hot springs. “I bathed in a small ravine where hot spring water surfaces beside the flow of a cold creek, a very rare sight,” he wrote. “Those who bathe in these waters will be cured of all illness.”

Hiking the Kumano Kodo in light of these layers of historical intrigue, every stone underfoot and boulder along the trail, every towering cedar and moss-covered shrine, every tumbling river and babbling brook becomes infinitely more interesting. If the hills had voices, one can only imagine the stories they’d tell.

The Trodden Trail: Nakahechi Route

I got my first real taste of the Kumano Kodo, right outside the entrance of the Kodokan, where we joined the Nakahechi route. A large engraved stone noted we were entering a designated World Heritage area. Behind this stood a stern torii gate indicating the entrance to Takijiri-Oji, the sacred entrance to the trail. A little further along, a wooden post erected beside a tree proudly stated two words: “Kumano Kodo.”

Our hike on this particular section of the Kumano Kodo was a testing of the waters, if you will. We trudged up a fairly steep yet well-trodden path for about 500 meters. Though we had it all to ourselves, Mike informed me that it’s typically more congested in less virulent times, especially during the spring sakura (cherry blossom) and koyo (autumn foliage) seasons. As we moved deeper into the forest, the air became more still as the sounds of cars on a nearby road faded, replaced by the snap of twigs underfoot and the chirrup of birds in the boskage overhead.

Our brief ascent culminated in a little red-bibbed jizo statue, a bodhisattva who guards travelers and the souls of the unborn, brooded over by a sacred rock. This “mother rock” was mythologized centuries ago, after tales spread of it protecting a baby left in its care for several days. Next to these was a natural tunnel in the earth leading to a small gap between two boulders, just about wide enough for an average-sized human to squeeze through. Safe passage through this tunnel, known as “the womb,” symbolizes the purification of your soul, part of an old Buddhist rebirthing ritual.

I am not a particularly large man, so I fancied my chances of braving the womb relatively unscathed. With some muffled grunting and an ungainly push, I succeeded in coming out the other side, in being reborn. I can’t say I felt entirely purified. Still, it was a great example of how the Kumano Kodo’s natural surroundings worked to symbolize the religious beliefs which had long attracted pilgrims to the region.

To the Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine

We descended the trail and regrouped at the car to make our way further along the Nakahechi route. We got back on the trail from a popular starting spot at Hosshinmon-oji, one of the hundreds of smaller shrines dotting the Kodo. Hosshinmon-oji marks the outermost entrance into the divine precinct of Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine, around five miles away.

From here, the Nakahechi led past farms, vegetable allotments, and the home of an old woodcarver who’d fashioned scarecrows for the neighboring farmers before it entered a forest of cryptomeria cedar, cypress, pines, chestnut, conifers, exotic-looking ferns, and countless other botanical species.

Deeper into the forest, we passed by an abandoned school, which was locked in a state of beauty and melancholy intertwined. Classrooms bereft of life and covered in debris looked out at an old swimming pool, littered in golden foliage dropped from deciduous trees clinging to the death throes of autumn. The sun reflected, mirror-like, on the pool’s deathly still surface, while moss crept up over the sides. I could have sat for hours just drinking it all in. Unfortunately, time was not on my side, so I made a quick offering at the school’s Jizo — said to cure the kind of backache I just so happened to be carrying — and proceeded onward.

“We are now re-entering the designated World Heritage area,” Mike told me as we arrived at a path of aging stonework. Much of the section we were about to step foot on had been preserved since the Heian Period, a relic of the old Kumano Kodo pilgrimage, undiluted by the modernization which has taken place around it.

The bumpy ancient road snaked through a forest of towering trees and slowly began to feel like the fabled land of the Shinto gods. Reality, or at least the modern world, felt lightyears (and literal years) away as we marched to the beat of our footsteps, to the rhythm of our surroundings, with only snippets of conversation here and there to break the environmental soundscape.

A number of small shrines peppered the sides of the road, many of which honored those who had walked the Kodo but failed to come back alive. It helped to put in perspective what it was like to walk these trails a thousand years ago, with no backpacks full of water and snacks, no GPS in your pocket if you stumbled off course, no guide who knew these woods like the back of his hands leading the way.

We continued to the approximate halfway point between Hosshinmon-oji and Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine, a small rest hut overlooking a tea farm that served onsen coffee (made with hot spring water). We tucked into our Kumano Kodo Bento (lunchbox) purchased in advance at Omuraya and enjoyed the much-needed warmth and energy from our steaming, caffeine-charged brews. (Please note that there are no lunch stops along this portion of the route, so please pack meals or snacks accordingly.) A viewpoint sat next door to the rest, providing unhindered views across the Kii Mountain Range rolling toward the horizon. On a clear December day, as it was for us, one can see 20-plus-miles into the distance: a several-day trek along the Kumano Kodo from where we were standing.

Entering the World of Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine

We walked for another couple of miles through a similarly serene forested landscape to reach the Kodo’s first grand shrine, Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine (熊野本宮大社). Just as all roads lead to Rome, all Kumano Kodo trails lead to this grand shrine, situated in the heart of the region.

All Kumano Kodo trails lead to the grand shrine of Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine situated in the heart of the region.

Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine enshrines a number of deities, including Amaterasu, and serves as one of the three sanctuaries of worship of over 3,000 Kumano shrines scattered across the Japanese archipelago. The Hongu shrine has existed for well over two thousand years. However, the current building, an austere structure sitting in a forest grove, was constructed at least 900 years ago — based on the diary of a traveling pilgrim — though it has been moved and rebuilt multiple times due to intermittent fires, floods, and disasters.

As we arrived at the complex, two things struck me. Firstly, the shrine’s hidden woodland setting, along with its relatively simplistic style, keep it shrouded in mystique. Grand architectural embellishments, such as the crossed blades on its sloping roof and the huge gated entrance, are among the limited signs suggesting Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine carries any more significance than your average Shinto shrine.

Secondly, three-legged crow iconography was everywhere I looked. I recognized it as the symbol of the Japanese football (soccer) team but had never considered its significance. During the aforementioned first emperor Jimmu’s journey to found Japan, a yatagarasu (three-legged crow) was sent as a messenger from heaven to guide the imperial legion through the potentially perilous Kumano region. As such, it is to this unlikely mythical creature that Japan owes its existence.

We walked through to the main shrine and paid our respects. Though it was partially concealed by barriers set up to accommodate the expected influx of visitors during the upcoming shougatsu, or New Year, it did little to detract from the shrine’s mystical charm.

Before the day was out, we had one last stop to make, the stone torii at Oyunohara, just a short stroll away. Standing 33-meters tall, it’s the largest torii gate in the world, nearly spinning my head into vertigo as I gawked directly up at it from the base. The gate marks the original location of Kumano Hongu Taisha Grand Shrine, which was moved to its current location in the 19th century due to flood concerns.

I soon bid Mike farewell and vowed to return to the Kumano Kodo as soon as the opportunity presented itself. I may have seen some of its finest sights that day, but really, I had barely scratched the surface.

The Rest of the Kumano Kodo Pilgrimage and Beyond

Due to time constraints, I sadly wasn’t able to continue hiking the trail that day or during the rest of my busy schedule in Wakayama Prefecture. However, I was able to visit the two other grand shrines and temple making up the Kumano Sanzan in the following days, along with several other historical sites in the region. I’ll detail some of the highlights below:

Kumano Nachi Taisha Grand Shrine

Perched on a hill in sight of the deified Nachi Waterfalls, Japan’s tallest single-drop waterfall at 133 meters, is Kumano Nachi Taisha Grand Shrine. During my visit, the pagoda of Nachisan Seiganto-ji Temple beamed vermillion in the glossy winter sun, while kaleidoscopic streaks painted the falls as sunlight refracted through the tumbling water droplets — a common occurrence on the clearest winter days. You can also access Kumano Nachi Taisha Grand Shrine and Nachisan Seiganto-ji Temple via the Daimon-zaka Slope, a sloping path skirting underneath towering cedars, which split the sunlight like a citadel’s windows; it feels like a godswood brought to life.

Kumano Hayatama Taisha Grand Shrine

Situated at the mouth of Kumano-gawa River, from where flows the Kii Mountains’ sacred waters, Kumano Hayatama Taisha Grand Shrine is the easiest of the grand shrines to access. Within the precinct is a wise-looking podocarpus tree over 1,000-years-old, which embodies the strong spiritual connection between the nature of the Kumano region and its inhabitants.

Kamikura-jinja Shrine

Located halfway up Mt. Kamikura, not far from Kumano Hayatama Taisha Grand Shrine, is one of the lesser-known yet most important spiritual sites in Japan. The Kamikura-jinja Shrine, a humble structure of red lacquered wood sitting under the stewardship of a sacred rock (called “Gotobiki-iwa”), is believed to be the spot where the Kumano deities first descended to earth. You’ll have to climb a seriously steep set of steps to reach it, but to see the origin of the gods, it’s one-hundred-percent worth it.

Yunomine and Kawayu Onsens

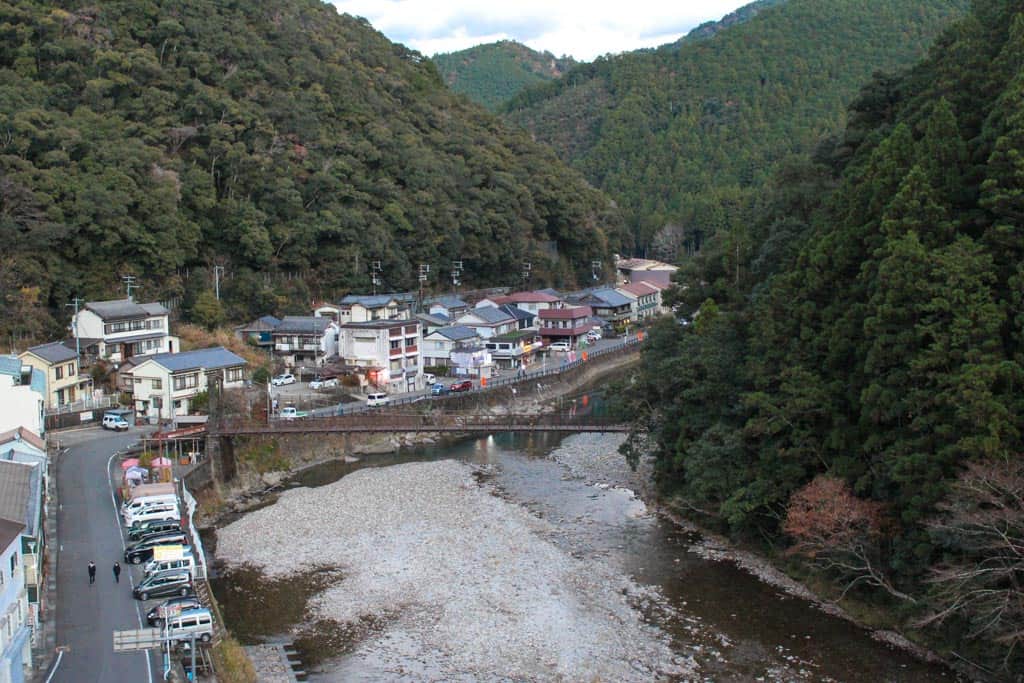

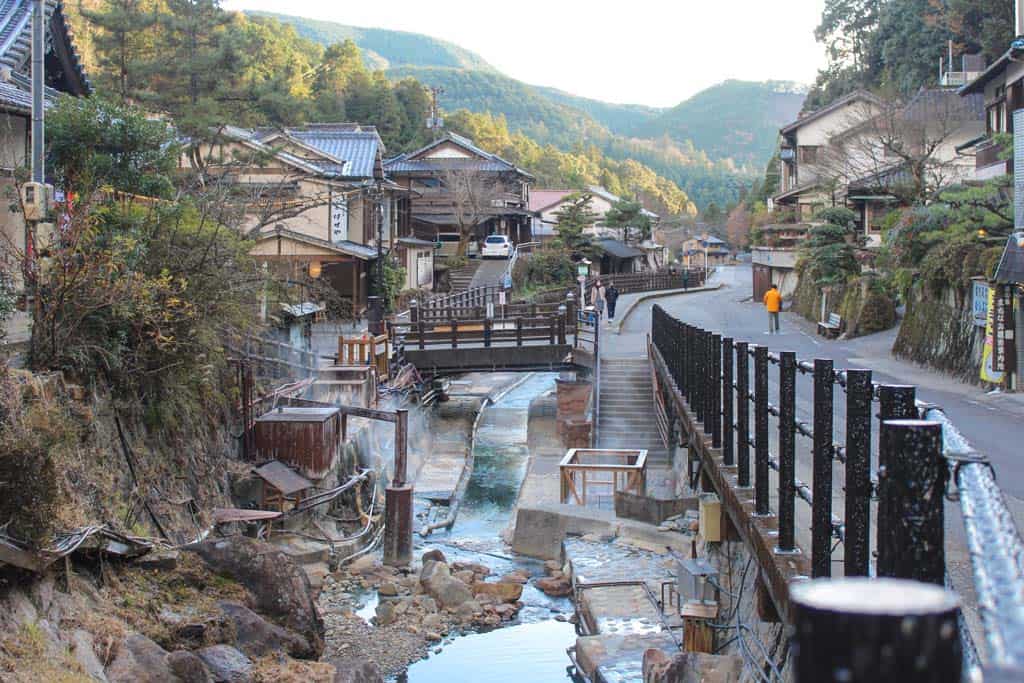

The aforementioned Yunomine Onsen is a quaint little onsen town believed to be home to Japan’s oldest hot spring (still in use), where you can also boil eggs or fresh vegetables in the bubbling waters. Kawayu Onsen, another small town in the Kumano region, has a bounty of natural hot springs connected to the central river tributary. In winter, there’s no better way to stave off the chill than a steamy dunk.

Kawayu Onsen

Yunomine Onsen is a quaint little onsen town believed to be home to Japan’s oldest hot spring (still in use), where you can also boil eggs or fresh vegetables in the bubbling waters.

Mie Prefecture

Next door to Wakayama is Mie Prefecture, home to some of the nation’s oldest and most important shrines (including the aforementioned Ise Jingu) and wild natural rock features.

Hana-no-Iwaya Shrine

The Hana-no-Iwaya Shrine is reportedly Japan’s oldest Shinto shrine, likely well over 2,000 years old. The actual construction at the shrine is very basic: a simple metal ornament within a wooden fence. However, this sits in front of an imposing 45-meter-tall rock that symbolizes the mother of the Japanese gods, Izanami-no-mikoto.

Hana-no-Iwaya Shrine is reportedly Japan’s oldest Shinto shrine at over 2,000 years old.

Hana-no-Iwaya Shrine sits in front of an imposing 45-meter-tall rock that symbolizes the mother of the Japanese gods, Izanami-no-mikoto.

Oniga-jo Rocks

Taking their name from the Japanese word oni (a kind of mythological troll demon), are the Oniga-jo Rocks covering a nearly one-mile stretch along the Kumano-nada Sea. There’s a footpath etched into the cliff face where you can walk past the fractured and toothy facades of rock that resemble mythical demons.

Shishi-iwa

The Shishi-iwa, from the word shishi (stone lion-like protectorates of temple and shrine grounds who usually come in pairs and ward of evil spirits), towers over Mie Prefecture’s Shichiri-mihama Beach. To me, the rock looked more like a squawking eagle, but either way, it’s undeniably impressive.

Kumano and Mie Hotel Recommendations

Kawayu Onsen Midoriya (Kumano Kodo) — Kawayu Onsen Midoriya is a pretty riverside ryokan (traditional inn) in the Hongu area — near the eponymous shrine — with outdoor hot springs connected to the river. An elegant kaiseki dinner (multi-course seasonal cuisine) and breakfast buffet is included for each night’s stay.

Iruka Onsen Seiryuso (Mie Prefecture) —Nestled on the banks of the Kitayama River, this quiet ryokan is a fusion of Japanese and western design styles. A kaiseki dinner and Japanese breakfast is included for each night’s stay, while the gorgeous Yumoto Sanso Yunokuchi Onsen is just ten minutes away via an old trolley car formerly used by local miners.

Access to Takijiri-Oji and Nakahechi Route

Takijiri-Oji is the easiest place to start your Kumano Kodo trek along the Nakahechi trail. Kii-Tanabe Station is the closest station to Takijiri-Oji. From Osaka, take a Kuroshio Limited Express train from Tennoji Station (天王寺駅) towards Shingu, and get off at Kii-Tanabe Station, then catch a 40-minute local bus to get to the Takijiri-Oji.

Sponsored by Chubu District Transport Bureau, Wakayama Tourism Federation and Mie Prefecture

No Comments yet!