At the heart of the Setouchi region, the four cardinal cities of Okayama, Hiroshima, Matsuyama and Takamatsu frame the Seto Inland Sea with a rich blend of history and modernity. Our journey unfolds across landscapes steeped in legend, through streets echoing with the resilience of the past, and into the warm embrace of cultural and culinary delights. As we cycle across the legendary plains of Okayama, reflect on the poignant shadows of Hiroshima, and wander the serene gardens of Matsuyama and Takamatsu, each step takes us deeper into the unique characteristics of each major port city.

Day 1: Following the Legends and Flavors of Okayama

From Okayama, we follow the Kibiji cycling route through verdant rural landscapes leading to the revered Kibitsujinja Shrine (吉備津神社). The air is thick with the folklore of Prince Kibitsuhiko, the brave and skilled archer destined to vanquish Ura. Ura was finally defeated by Prince Kibitsuhiko after a violent series of shape-shifting pursuits across the Kibi plain, where his decapitated head continues to haunt the sacred cauldron of Okamaden at Kibitsu Shrine to this day. At the entrance of the shrine, the imposing presence of Yaokiiwa, the legendary rock where Kibitsuhiko laid his arrows, whisks us back in time to the scene of the local legend.

Inside Okamaden Hall, the solemn Narukama ritual (鳴釜神事) is meant to appease the anger of Ura’s howling spirit, recalling Ura’s promise to tell people’s fortunes or misfortunes. The crackling fire beneath the cauldron, accented by natural light filtering through the square room’s black wooden walls, creates an otherworldly ambiance. The Shinto priest, clad in a bright green robe, channels an invisible energy into his chants, while the azome, representing Ura’s wife Azohime and dressed in pure white, tends to the burning cauldron. At the climax of the ritual, the iron pot releases a low, steady rumble that resonates within the intimate wooden chamber—inviting us to reach our own personal interpretation of its legendary roar.

For lunch, local traditional cuisine is served. Demi katsudon is a highly guarded local culinary tradition, and it is fried pork cutlet with demi-glace sauce. It’s a popular local dish in Okayama, with each establishment serving up unique flavors. The original owner of the restaurant first learned how to make demi-glace while working at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, but as the recipe was intended for Western cuisine, he tailored the flavor and texture for a more Japanese palette, better paired with white rice. Katsudon Nomura’s original house sauce is indeed reminiscent of Western-style barbecue sauce, but its sweeter taste enhances the pork flavor and blends perfectly with the tenderness of the katsudon.

Just across the Asahi river from Okayama’s bustling city center, Okayama Korakuen Garden (岡山後楽園) preserves the serene atmosphere of Lord Ikeda Tsunamasa’s Edo-period leisure grounds. The garden is full of varying landscapes, including vast ponds populated by colorful koi, strategically placed rest houses, tea fields, bamboo groves, stepping stones and wooden bridges, even a small waterfall. Okayama’s Ujo Castle can be seen, poetically framed by pine trees on the northern end of the garden. Yuishinzan Hill provides a panoramic viewpoint of the premises, but it’s always a pleasure to greet the live carp gathered by the stone steps of Sawa-no-ike, or to visit the endangered red-crowned cranes inside their dedicated aviary, still kept at Okayama Korakuen as Japanese symbols of luck and longevity.

A shaded path full of birdsong outside Korakuen’s South Gate leads across Tsukimi Bridge to Okayama Castle (岡山城), where the gradual approach is all the more dramatic after seeing the castle from the garden. Most striking are the black weatherboards of “Black Crow” Ujo’s main tower. Like Oda Nobunaga’s Azuchi Castle and Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Osaka Castle, its façade is descended from the lineage of castles by the great masters. The unusual pentagonal base of the castle keep, supported by high stone walls, is best viewed from the riverside path. While the historic tenshu, built around 1597, is reconstructed, Okayama Castle’s original Moon-viewing Turret (Tsukimi Yagura) watchtower remains intact and in place on the current grounds.The main tower’s 5th and 6th floors offer splendid views all around, from pedal boats on the river moat to Korakuen’s tea fields to the surrounding cityscape and extended mountain range, accented by bright gold shachihoko on black-tiled rooftips.

Hamoji (八文字) , who kindly cooperated with our coverage, is a specialty restaurant in Okayama known for its Seto Inland Sea seafood and sushi-centric Okayama cuisine.

Perhaps the most notable menu item is barazushi, a local dish beloved for its beautiful arrangement of seafood and seasonal vegetables. Barazushi in Okayama is a gorgeous dish consisting of a rich assortment of ingredients that are individually cooked and seasoned. Barazushi is traditionally enjoyed on special occasions such as festivals and celebrations. We also couldn’t resist the sweetly vinegared mamakari (Japanese sardinella, also known as sappa), another typical Okayama dish that is traditionally served on special occasions – decapitated, scaled and gutted, with shimmering golden tails. The amusing name mamakari is a wink at how irresistibly tasty the sushi is, so much so that more rice (mama) must be borrowed (kari) to keep up with the fish.

Day 2: Echoes of the Past while Embracing the Future in Hiroshima

The city of Hiroshima is exceptional in its ability to come to terms with its traumatic past, while finding new and creative ways to engage with a brighter future.

Reflecting on War around the Peace Memorial Park

Each visit to the skeletal ruins of Hiroshima’s Atomic Bomb Dome (原爆ドーム) is a sobering reminder of the unspeakable horrors of August 6, 1945. As we approach from behind, the stone monument to the spirits who perished in the nuclear blast sets a solemn tone. Circling around it toward the river, we hear an elderly volunteer recounting bits of history to the crowd gathered around him. Looking up at the Dome from the ground, we can see the detailed impact of the atomic explosion on the building’s broken granite, shattered brick walls and distorted iron rods. We pause on the riverbank near the top of the steps, where dead bodies once washed ashore, to examine an odd-shaped block of granite disguised as a bench: the only part of the Atomic Bomb Dome ruins that we are allowed to touch, according to the guide. No doubt the best views of the Dome are from just across the river, where the ruins are put into the larger perspective of the city that has since redeveloped around it.

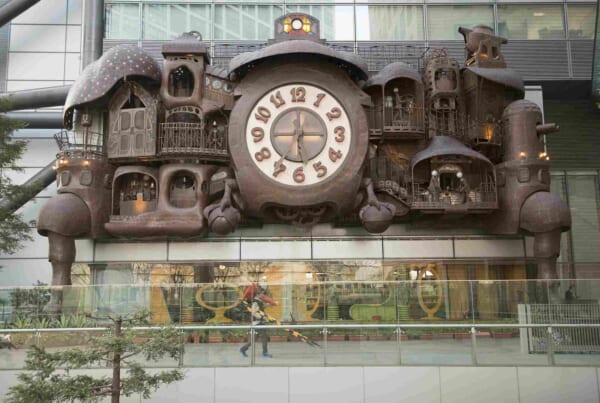

From within the Peace Memorial Park (平和記念公園), we embrace the vastness that commemorates the victims of the bomb. The Bell of Peace gongs our good wishes, as we honor the Memorial Mound, marking unclaimed cremated remains, and the turtle back memorial to Korean victims. Schoolchildren diligently take notes, suggesting the promise of remembrance across generations. High school students conduct a commemorative ceremony by the Children’s Peace Monument, surrounded by countless donated orizuru chains of folded paper cranes. Just across the walkway, the former Fuel Hall basement preserves the chamber where Eizo Nomura, a lone staff member retrieving archives at the time of the blast, survived underground. As we walk through the park grounds, the geographical scale of the devastation looms heavily in my heart, yet the park itself remains a testament to Hiroshima’s unwavering message of peace and resilience.

Reframing the views of Hiroshima’s past, present, and future

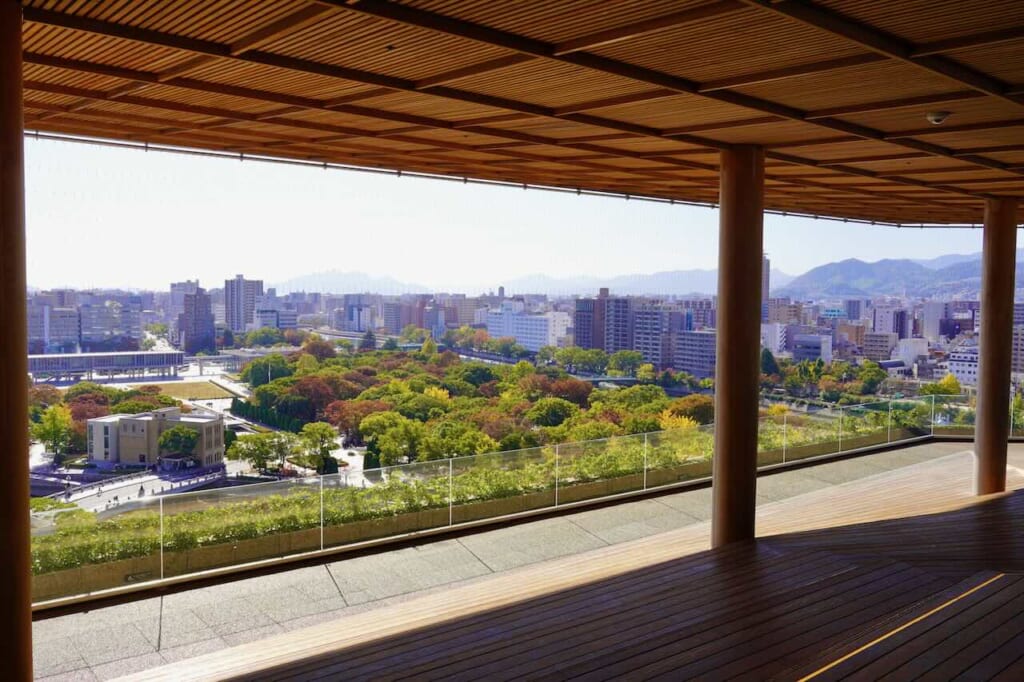

HIROSHIMA ORIZURU TOWER (おりづるタワー), a modern edifice rising near the Peace Memorial Park, stands as a symbol of Hiroshima’s forward-looking spirit. Its rooftop observation deck offers a sweeping view that juxtaposes the city’s painful past with its hopeful future. Also clearly visible is the guiding line starting from the Prayer Fountain, going through the Park past the Peace Flame, the Children’s Peace Monument and the Atomic Bomb Dome, to the Hiroshima Green Arena, widening to include the brand-new Edion Peace Wing Stadium on the left, and the ancient Hiroshima Castle on the right. The tower’s moving “ORIZURU WALL” invites visitors to contribute to a growing cascade of paper cranes, each one a wish for peace, where I fold and drop my own crane into this collective prayer. On the building’s southeast corner, the refreshing WALL ART PROJECT “2045 NINE HOPES” showcases 9 floors of bold and colorful murals by Hiroshima-related artists ranging in age from twenties to nineties. The theme is Hiroshima 2045, one hundred years after the atomic bombing, as we imagine brighter views of our not-so-distant future.

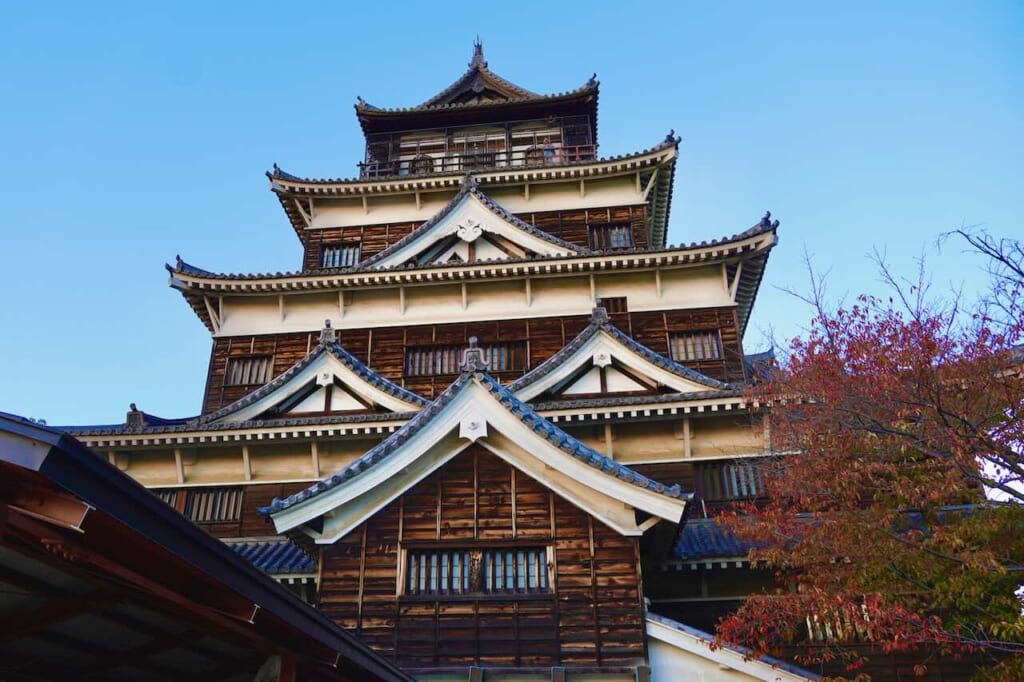

Established more than 400 years ago at the end of the Warring States period, the reconstructed, symmetrical, wood-paneled Hiroshima Castle (広島城) is still an elegant sight. Although today the relatively subdued tenshu is somewhat dwarfed by its shiny new neighboring structures, the wide moat and thick stone walls insulating the castle grounds from surrounding urban development effectively preserve its iconic status.

The castle-museum exhibits intriguingly recreated chamber interiors, as well as an impressive collection of finely crafted artisanal swords. After contemplating the modern cityscape from future-forward Orizuru Tower’s rooftop observatory, the views from the top of Hiroshima Castle seem to zoom in on the scene from a more intimate distance just across the reflective moat water, as if seeing the present from the past. Go at dusk on a clear day to catch the sunset, then turn around as you leave to admire the castle gracefully lit up at night.

Making Hiroshima-Style Okonomiyaki at OKOSTA

If you’ve ever marveled at the mouth-watering efficiency of chefs who can whip, toss, and grill an entire Hiroshima-style okonomiyaki from scratch in mere minutes, OKOSTA okonomiyaki experience studio (お好み焼き体験スタジオ) shows you exactly how it’s done, so that even the uninitiated can do-it-yourself in less than half an hour.

A skilled chef guides us through each step of the Hiroshima-style layering process, from batter to bacon to soba to egg and everything in between, all stacked to sumptuous perfection and topped with the sauce of our choice. Timing the grilling just right may be the biggest challenge, as taste and texture distinguish amateur from master—the professionally crafted okonomiyaki, using the exact same ingredients, is notably firmer and crispier where it counts. Still, nothing beats the joy of eating your own creation!

Encountering the Cultural Spectacle of Hiroshima Kagura

The evening Hiroshima Kagura (ひろしま神楽) performance almost splashes off the stage with its vibrant energy and color, from the Shinto quartet of taiko drums and flute to the extravagant costumes and swirling dances. Tonight is the “Tsuchigumo” drama about the politically oppressed “earth spider” demons of the shogunate era, who rose above land to attack the shogun and reclaim power… only to be defeated by the magnificent white-haired shogun, his faithful retainers, and his heirloom sword. The show is full of sword fighting and displays of power and vengeance, while the vivid pace keeps the dramatic tale of folklore heroes and mythical creatures moving along with spectacular choreography and live music.

The performers’ dedication to their art is clearly on display, and posing with their elaborate costumes after the show adds a personal touch to this lively encounter with one of Hiroshima’s cherished cultural expressions.

Retreating to the Seaside Tranquility of Grand Prince Hotel Hiroshima

The day concludes as we check-in at Grand Prince Hotel Hiroshima (グランドプリンスホテル広島), a self-contained resort on Ujina Island. Renowned for hosting the G7 Summit in May 2023, the hotel proudly displays memorabilia from this significant diplomatic event around the lobby. While all the rooms provide unobstructed sea views, the Top of Hiroshima lounge on the 23rd floor offers panoramic vistas alongside gourmet offerings, from the buffet breakfast to the evening bar. The soothing common baths overlook the sea from dawn to dusk, so it’s best to go in the morning to watch the sunrise.

On the ground floor, almost at sea level, an inviting, perfectly round, shallow outdoor swimming pool reflects the sky and offers another quiet space to feel at one with the seascape.

Day 3: Blending Tradition and Modernity in Matsuyama

Fresh off the SuperJet ferry from Hiroshima port, our visit to Matsuyama begins with a delightful lunch at KADOYA (かどや), located at the bustling intersection near Okaido Shopping Arcade. The warm and minimalist decor of the underground dining space sets the stage for elegant cuisine. The restaurant’s signature Uwajima tai meshi is a flavorful ensemble centered around plump strips of sea bream sashimi piled onto a shiso leaf, resting on a clamshell inside a sea bream-shaped dish. Mix the raw egg with the dashi sauce, dip your sashimi and shiso into the sauce, down it with white rice. While the tai sashimi is already fresh and tasty, dipping it in the egg and sauce gives it a more delicate taste and texture.

After lunch, we meander along the clean Matsuyama Ropeway Shopping Street (松山ロープウェー商店街), from Kadoya to the ropeway stop for Matsuyama Castle. The street is a single wide road under the open sky with no visible power lines and a view of the mountains on the horizon. The path is lined with shops selling traditional handicrafts, fun foodie shops offering local treats such as jakoten deep-fried fish cakes, and many fine restaurants specialized in Ehime’s famous tai meshi (sea bream rice). About halfway up the street is Smiley Ehime Official Souvenir Shop, which offers tourism information and a selection of Ehime goods. You can even pour yourself a cup of tangy mandarin orange juice from a faucet! It’s a great place to refresh with delicious orange juice while sightseeing.

Matsuyama Castle (松山城) has one of only 12 existing castle towers in Japan built before the Edo period. What catches the eye even from a distance is its distinctive architectural style, characterized by a towering Tenshu (Main tower) surrounded by Ko-tenshu (Small tower) and turrets, known as “Renritsushiki.” Perched at an elevation of 132 meters, this commanding structure stands out prominently. Once you approach the castle, it becomes evident that this beautiful structure atop the hill is a formidable fortress designed to thwart enemy attacks. The enemies may mistakenly believe they have reached the vulnerable entrances of the castle, such as the gate without doors (Tonashi-mon Gate) or gates utilizing tricks based on the angles of the stone walls (such as Tsutsui-mon Gate and Kakure-mon Gate). Inside the meticulously restored main keep, polished wooden stairs connect multiple levels beneath lofty ceilings. As one navigates through maze-like corridors, they encounter a plethora of notable artifacts, including armor and weapons from the Edo period, writings on scrolls, graffiti on plaques, and other remarkable collections.

The ultimate reward awaits at the summit: the panoramic view of the fortress from above. Surrounded by dense forests on a hilltop, one can oversee the entire castle grounds, with the sea stretching out to the west.

Praying as a Pilgrim at Ishiteji Temple

Visiting Ishiteji (石手寺), the revered 51st temple on Shikoku’s 88-temple pilgrimage route, is an immersive experience of its spiritual rituals. Donning the traditional sugegasa hat, light purple sash, white vest, and carrying the symbolic Kongo-zue (a wooden staff), I embark on a meditative journey through the temple grounds. Ritual cleansing before walking through the national treasure of Niomon, fingering the woven straw “healing” gate adorned with coins, and the gentle gong of the giant bell enrich the sensory experiences of reciting sutras at designated spots, caressing a stone egg to clear mental troubles, smelling the burning incense and feeling the gravel underfoot.

Before leaving Ishiteji, I touch each bag of transplanted sacred sand, in an 88-temple shortcut that begins and ends at Koyasan.

Engaging with the Timeless Continuity of Dogo Onsen

Matsuyama’s historical Dogo Onsen district is a destination in itself. The hot spring town’s famous symbol, Dogo Onsen Honkan (道後温泉本館), is believed to be Japan’s oldest public bathhouse—mentioned in ancient Japanese texts, immortalized in Natsume Soseki’s 1906 novel Botchan, beloved in Hayao Miyazaki’s 2001 animated film Spirited Away. Amidst ongoing restorations, the active bathhouse is just as mystical and historically significant—most notably three times a day at 6am, midday, and 6pm, when each strike of the Tokidaiko(time drum) resonates with centuries of tradition and creates a unique bathhouse atmosphere. The sound of this Tokidaiko(time drum) was selected as one of the “100 Japanese Soundscapes to Preserve”.

The Botchan Karakuri Clock (坊っちゃんカラクリ時計) is no doubt one of the most endearing and crowd-pleasing manifestation of Dogo Onsen’s popularity, reuniting several disparate elements into an enchanting performance. The clock is modeled after the Shinrokaku of Dogo Onsen Honkan, and at a predetermined time, the clock tower rises to the sounds of a lovely melody, revealing the characters from the novel Botchan.

Our day in Matsuyama culminates with a stay at Dogo Kowakuen Haruka (道後温泉 ホテル古湧園 遥). Opened in 2019, Haruka is the latest example of an ultra-contemporary resort building adding new upscale accommodation options with eco-friendly flair to Dogo Onsen, while respecting the historical district’s cultural heritage. This contemporary oasis notably offers a panoramic view from the upper-level suite balconies that extends from the historic Honkan to the vibrant shopping arcade and newer red-painted Dogo Onsen Annex.

On the top floor, the hotel’s modern baths, both shared and private, overlook the cityscape with mountains on the horizon. Also inside the room is a selection of yukata, so it’s easy to wear them with the wooden geta to go out onsen-hopping, especially with a direct private exit from the hotel lobby down to chic cafés and Honkan just below. After an elegant gourmet dinner served on glass and Tobeyaki dishware, the evening concludes with a soothing live piano concert in the lobby.

Day 4: Serenity amidst Historical Splendor in Takamatsu

In Takamatsu, the 16-hectare, roughly 400-year-old Ritsurin Garden (栗林公園) is a sprawling testament to both power and peace. It was originally built in the southwest “Shofuda” area in the late 16th century by the Sato clan, a local ruling family. Then, the Ikoma clan and the Matsudaira clan took over to develop, expand, and enhance the garden. It took the Matsudaira’s more than 100 years to complete in 1745. At a time when the motto might have been “make gardens, not weapons”. It was used as the villa of 11 generations of the Matsudaira family for 228 years until the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Since Ritsurin Garden opened to the public in 1875, it retains its carefully landscaped Edo-period (1603-1867) feel, with the added charms of strangely shaped rocks and expertly groomed pine trees by dedicated bonsai gardeners. Light rain lends a reflective sheen to the scenery, enhancing the garden’s vivid colors and vibrant koi ponds, while subtropical sotetsu palms add an exotic touch. Across the jade water, a woman dressed in kimono poses for photographs in the open tatami rooms of the Kikugetsu-tei Teahouse. We stroll through the alley of seemingly interwoven tall Byobu-matsu and low Hako-matsu pines, before visiting the giant Neagari Goyo-matsu pine, Tsurukame (crane-turtle) pine, and the five O-teue-matsu pines planted by Japanese Imperial Family and British Royal Family members in the Taisho period (1912-1926). In addition, there is another imperial hand-planted pine tree next to Kikugetsu-tei. It was planted in 1903 by Emperor Taisho when he was the Crown Prince.

For lunch, we take shelter from the rain in an old-style cafe right beside the hungry koi of Nanko pond. Tempted by mystery, I order the Ritsurin udon, which turns out to be a delicious bowl of thick and chewy udon in a hot savory broth topped with fish cakes, wakame, and a whole baby octopus. It’s a surprisingly rich and flavorful meal that seems to embody both the sumptuous atmosphere of these historical gardens and the bountiful seafood blessings of the Seto Inland Sea.

Takamatsu Castle (高松城) is known as one of Japan’s three great seaside castles, constructed on the Seto Inland Sea. Even if what remains are scant structures and reconstructed bits, it’s fascinating to contemplate the stone walls surrounded by the still waters of the imposing moat from the tenshu ruins observation deck, or even closer up from a dedicated boat ride. Observe and admire the hydraulic engineering mechanics of drawing seawater into moat, then don’t forget to feed the resident sea bream before you leave. Sayabashi, a reconstructed long wooden walkway that bridges the honmaru castle core and the protective ninomaru enclosure, also serves as a symbolic crossing over into the city’s imagined past. As Takamatsu Castle and Ritsurin Garden are bound by the same daimyo who occupied them—the Ikoma lords of Sanuki Province, followed by the Matsudaira lords of the Takamatsu domain—the historic sites still seem to convey power through absence, like a historical hole full of stories, right in the city center.

Reflecting on this voyage through Okayama, Hiroshima, Matsuyama and Takamatsu, I cherish vivid memories and intriguing insights into the unique character of each city bordering the Seto Inland Sea. May you also experience the joys of discovering histories, legends and other cultural pleasures, paired with the exquisite flavors of Setouchi’s regional cuisine!

Sponsored by Matsuyama City.