Japan is a country of consumption. Commercial solicitations are everywhere, in supermarkets, shopping centers (depato, デパート) and konbini (コンビニ), and in the convenience stores open 24 hours a day. In-store, overwrapping is on the shelves of all departments, and shopping without plastic is a challenge. As a result, waste accumulates at breakneck speed, and the delicate question of their treatment arises. Amid mountains of plastic, let’s look into why there is so much in the first place, challenges with waste management, and new green initiatives.

- The Culture of Overpackaging Food Products

- Why Such An Abundance of Packaging and Plastic?

- Other Daily Disposable Items in Everyday Life

- How Does Japan Practice Selective Sorting and Waste Collection?

- How Does Recycling and Waste Disposal Work in Japan?

- Japan’s Future Waste, Ecology, and Environmental Goals

- Moving Towards Better Waste Reduction and Recycling in Japan

- Kamikatsu, the Zero Waste Japanese Village

The Culture of Overpackaging Food Products

Does Japan use a lot of plastic? Yes, plastic is deeply rooted in everyday life, and Japan is the world’s second-largest producer of plastic waste per capita, behind the United States. In 2018, the annual national plastic production was 9.4 million tonnes.

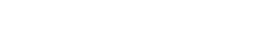

It is difficult to go shopping without also stocking up on plastic. Meat and fish are packaged in plastic or polystyrene trays, covered with cellophane. Some fruits and vegetables are packaged in batches in these same trays and/or covered with a plastic film. Some fruits and vegetables, such as mangoes, melons, and even carrots or peppers, are sometimes individually wrapped. Pears, persimmons, peaches, and citrus fruits are often even protected by a polyester net on top of the tray and the plastic wrap. It is hard to avoid. Even loose fruits and vegetables are wrapped in small plastic pouches at the checkout. And overpacking is ongoing even in so-called “natural” product stores.

In addition to the concern for product protection, individual portions are common. Biscuits are often packaged in individual plastic bags, and sometimes gathered on plastic trays.

During the checkout, plastic is used again. Meat and fish trays and some small products are rewrapped by the cashier in another plastic pouch. It is still possible to politely refuse this additional packaging, but in the land of conformism, the approach is not natural and is often considered with surprise.

After the checkouts of supermarkets, tables are available to pack the purchases. And once again, plastic pouches are in self-service. They are quite often used to avoid dirtying the bags during carriage.

Why Such An Abundance of Packaging and Plastic?

As we said, Japan is a big consumer of plastic. But why are the Japanese so little green? The cult of packaging is deeply rooted in tradition, and the cult of plastic can be explained by several cultural factors.

In Japan, the packaging is almost as important as the content. This is especially true when it comes to gifts. The Japanese take great care in their packaging. As proof, furoshiki (風呂敷), the traditional Japanese technique of folding and knotting fabric, is a full-fledged art. Even for everyday consumer goods, the packaging, even plastic packaging, stands for the quality of service and gives the product a luxurious touch.

Another reason for plastic use is that it guarantees cleanliness. Care of hygiene is essential in Japan. The more and the better the product is wrapped, the better it will be protected. Plastic is cheap, sturdy, and hygienic.

Japan is also a major consumption society. Commercial solicitations are everywhere: in shopping centers, in the very dense commercial fabric of supermarkets, drugstores and konbini, even on train station platforms, with ekiben kiosks (駅弁, station bento), in the streets, and sometimes even in the temples, with beverages vending machines (jidohanbaiki, 自動販売機). Japan owes its economic achievement to a strong and sustained domestic consumption.

Other Daily Disposable Items in Everyday Life

At the restaurant, disposable chopsticks are often used. They are made of wood, but still…

Those disposable chopsticks are available at checkouts in supermarkets and konbini. Canteens are rather rare, which requires employees who haven’t brought their bento box (弁当) to buy their lunch in individual portions at the konbini. On the menu: ready-made meals packed in plastic or polystyrene trays, sliced fruit presented on plastic trays, apples or bananas sold individually and wrapped in plastic bags; and concerning drinks, soda in a can, green tea in a plastic bottle, or a café latte in a plastic cup (with a plastic straw), or, at best, a single-served fruit juice in a cardboard packaging. The reheated dish and the cold drink are packed in two separate bags. And this is how the lunch break turns into a plastic feast…

Ready-made meals in a konbini

When it rains and you don’t have an umbrella case, plastic sleeves are available at the entrance of shops, restaurants, businesses and administrations. Before entering, visitors slip their umbrella into the sleeve to prevent it from dripping.

Ultimately, plastic waste represents about 37 kilos per capita per year in Japan. Packaging accounts for more than half of Japanese household waste by volume and almost a quarter by weight. According to the Ministry of the Environment, plastic packaging accounts for 68% of plastic waste generated in Japan.

How Does Japan Practice Selective Sorting and Waste Collection?

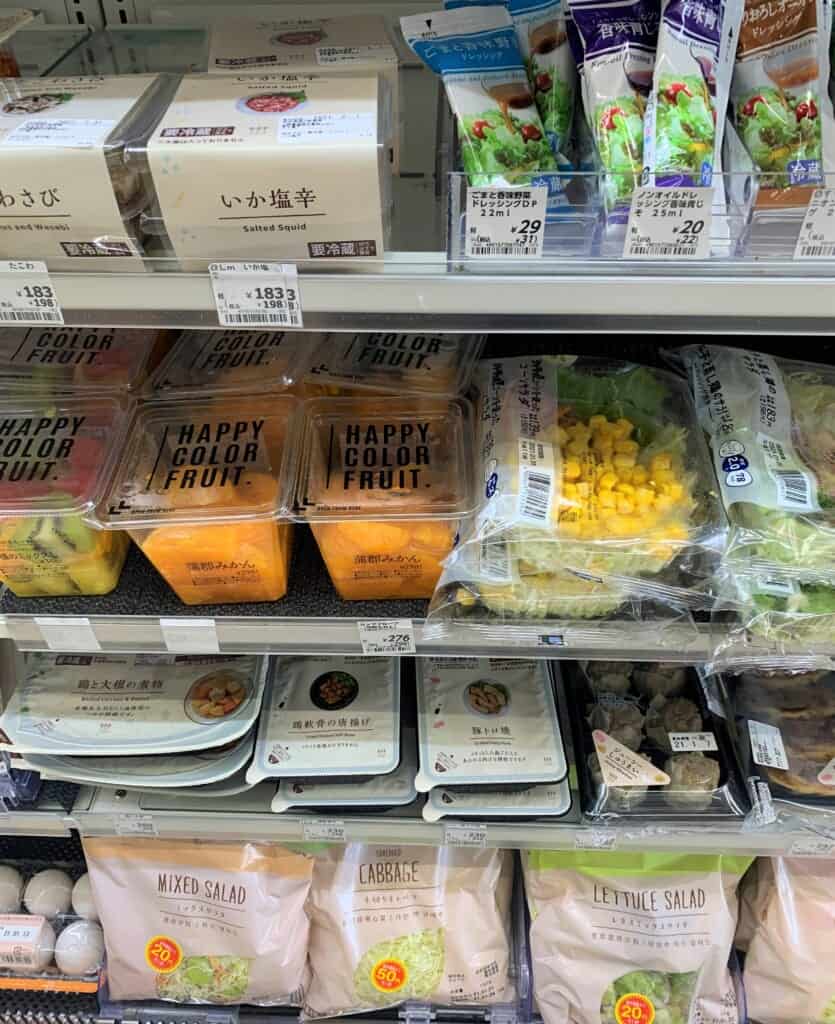

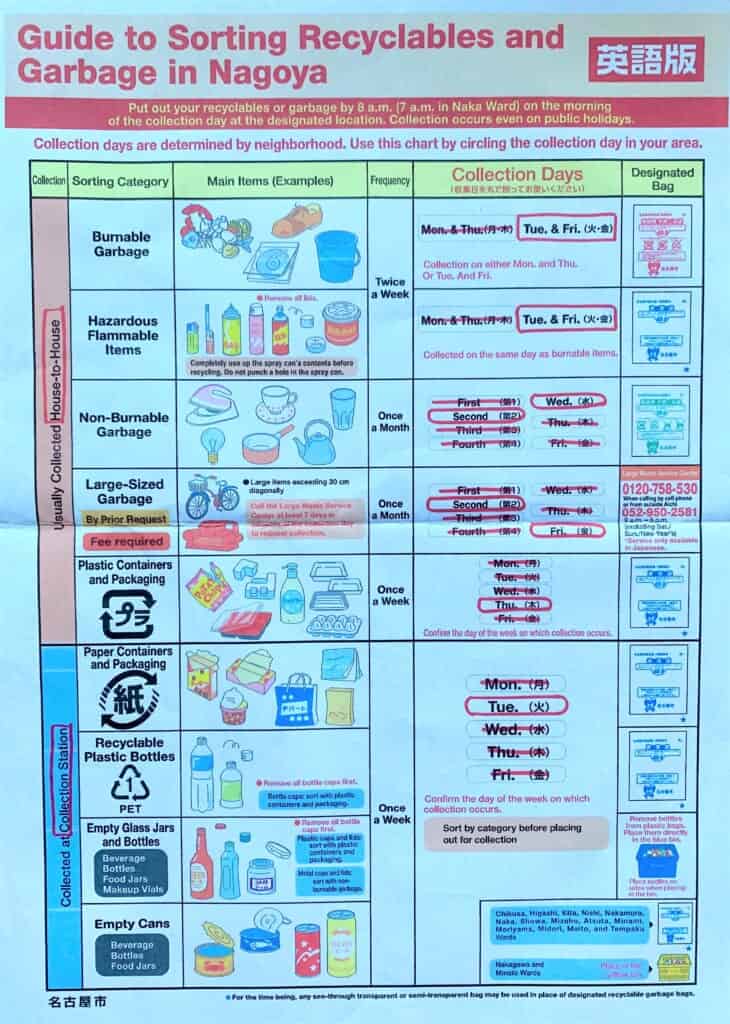

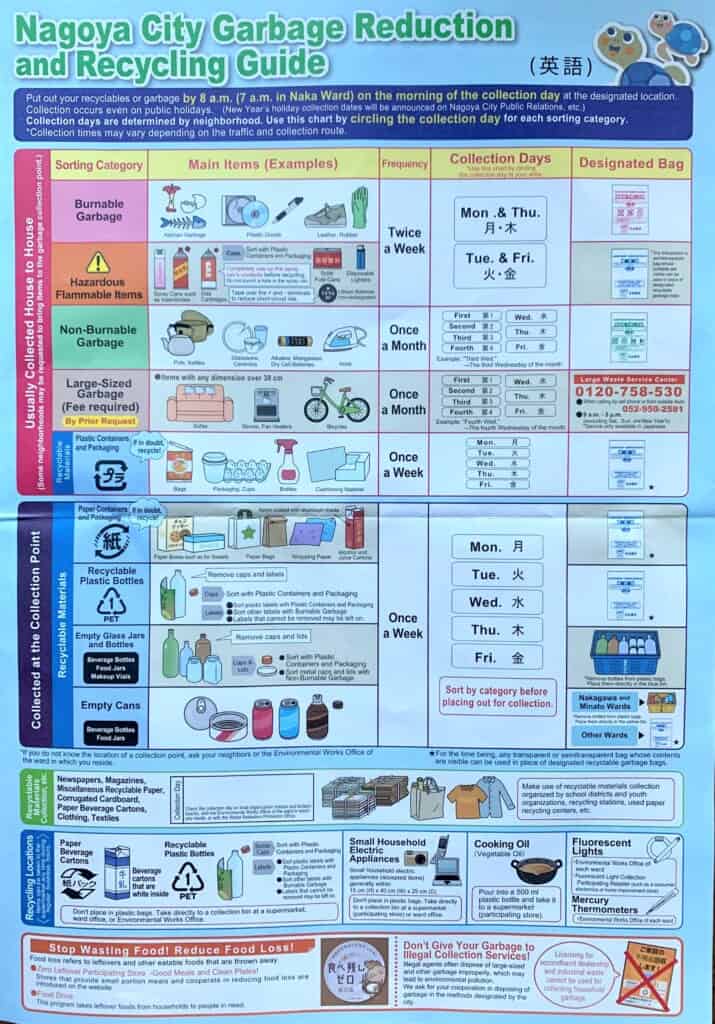

After these somber assessments, we must say that the Japanese carefully practice selective sorting. And when we talk about sorting, it is much more selective than what is done in Europe. Since the end of the 1990s, the municipalities have implemented very strict selective sorting rules. They are summarized in booklets that are sometimes so detailed that sorting can turn into a headache for the novice.

In Japan, it is not uncommon to have at least four or even five different bins that must be collected in specific bags: the garbage can for combustible waste, the bin for plastic waste, the bin for cardboard waste, the bin for glass, and the bin for cans and jars. At a minimum, combustible waste is separated from non-combustible waste, and at least one product category is sorted. Plastic is often separated from cardboard.

Collection points with recycling bins are also available at the entrances of supermarkets, some drugstores, and shopping centers.

Newspapers, cardboard and corrugated cardboard, non-combustible waste (porcelain, ceramics, metal products, etc.), and flammable products are sorted in other specific bins and separately collected. To ensure that waste is collected, it is necessary to carefully assemble newspapers, food cartons, and cardboard into regular, tied bundles.

Concerning the collection of bulky items, it is generally necessary to book an appointment, print a voucher, and take out the item(s) at the specified time, along with the voucher(s). In other words, you cannot just throw anything away!

And although all these rules are very strict, they are usually scrupulously enforced by residents.

How Does Recycling and Waste Disposal Work in Japan?

After sorting, how does recycling work? Three-quarters of the waste is incinerated, only one-fifth is recycled, and the rest is buried in landfills.

Concerning plastic, only a small amount is recycled. Even if plastic waste is widely sorted, nearly 80% is burned. 55 to 70% of plastic waste undergoes “thermal recycling,” which is transformed by combustion into thermal energy and electricity. Only 23% of plastic waste is recycled to produce other materials. The rate of mechanical plastic recycling doesn’t really occur because Japan doesn’t have infrastructures adapted to cleaning waste.

As for plastic bottles, each Japanese consumes an average of 183 bottles each year. But the recycling rate is better: 85% of them are recycled, one of the highest rates in the world, with a target of 100% by 2030. Plastic bottles are transformed into other bottles or into synthetic fabrics.

But on a national scale, storage and recycling capacities are saturated: treatment plants are lacking, and the Japanese archipelago runs out of space. The Japanese Ministry of the Environment has asked municipalities to do their part by incinerating plastic waste from companies. But the incineration of waste generates carbon dioxide and greenhouse gases, and even their burial generates soil pollution. And the mountains of plastic are responsible for the pollution of the seas.

So, in reality, Japan exports the majority of its sorted waste. Until 2018, nearly three-quarters of sorted waste was sent to China to be recycled… or incinerated. But in 2018, the rapidly expanding China banned these toxic and unprofitable imports. Japan was unprepared for such a concentration of waste, directly resulting from its consumerist model. Exports have been partly shifted to other Southeast Asian countries: Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia. But some countries, like Thailand, are, in their turn, considering banning these imports. The plastic and waste treatment problems in Japan are far from being solved.

Japan’s Future Waste, Ecology, and Environmental Goals

The government has recognized the unfolding ecological drama and the urgency of the situation, both in terms of waste reduction and recycling. The issue is regularly on the agenda at various political summits. As part of the G8 Summit in 2004, Japan launched the “3R” Initiative (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle), intended to promote a society that respects material cycling. So far, the program has a mixed picture: while recycling has been improved, there is still a long way to go concerning the first two components, “Reduce” and “Reuse.” During the Kobe Environment G8 in 2008, Japan announced the Action Plan for Global Zero Waste Societies. Reducing plastic waste was once again on the agenda at the G20 Summit in Osaka in 2019.

In January 2019, the Plastic Smart Forum brought together nearly 40 companies and non-profit organizations. In the same year, Environment Minister Yoshiaki Harada presented a recycling strategy to reduce single-use plastic waste by a quarter by 2030.

This ambitious scheme included the switch to compulsory invoicing of plastic bags before the end of 2020. After some reluctance, it is now done. Since July 1, 2020, plastic bags have been chargeable at the checkout. The businesses now bill customers for a nominal sum ranging from 3 to 10 yen. The government wants to encourage the Japanese to reconsider their consumption patterns. Some brands like Seico Mart have adopted bags made of bioplastic, materials of plant origin based on sugar or corn.

But to achieve Japan’s ecological goals, billing for plastic bags is not sufficient. Yoshiaki Harada’s plan also includes promoting the use of products made from carbon-neutral and plant-based bioplastics or derived from renewable sources. Researchers have developed vegetable plastic made from biodegradable polymers. Also, Japan has begun searching for new partners on the corporate side. Because as everywhere, companies often blame the consumers.

Moving Towards Better Waste Reduction and Recycling in Japan

However, it is not all doom and gloom. Some manufacturers are looking to replace traditional plastic packaging with greener alternatives. The famous KitKat brand now packs its chocolate bars in cardboard bags. The konbini store chains are also making efforts. 7-Eleven replaced the plastic wrappers of onigiri with a material derived from cane sugar. Family Mart now uses recycled plastic for noodle wrappers, and Seico Mart has undertaken several initiatives to reduce plastic use.

Widely invested in recycling, Osaki, in Kagoshima prefecture, southern Kyushu, is considered a model of selective waste sorting. Waste is divided into 27 categories, and 25 types of waste are fully recycled. The recycling rate is over 80%, the highest in Japan.

Some citizens themselves are committed to ecology in Japan through collectives and associations. The Internet sees the emergence of many sites and Instagram accounts that promote waste reduction and recycling, such as zerowaste.japan, PlasticObsessedJapan or zerowastejapan.

Japan lacks infrastructure and space to recycle. Another track is therefore being explored: building artificial islands on plastic that could not be recycled. And it has already been the case in Tokyo! The futuristic district of Odaiba has been extended on new artificial islands, built on embankments and polders made of recycled plastic waste. Rebuilding on waste is quite a statement.

Kamikatsu, the Zero Waste Japanese Village

Private initiatives are emerging, such as the Kamikatsu Zero Waste Village, a Japanese village between the mountains and the rice terraces of Shikoku. It is part of the international “zero waste” movement, promoting the reuse of waste, compost, and recycling.

Upstream, this movement is committed to reducing waste. It encourages a cleaner industrial system and less reliance on toxic products contaminating landfills and incinerators. Downstream, it encourages more virtuous consumption practices. The goal is “zero waste.”

Kamikatsu’s Zero Waste Academy coordinates these efforts. It encourages manufacturers to facilitate recycling and fight against illegal dumping and works to change attitudes. It also advocates that local governments stop incinerating waste in landfills.

Japan faces an overproduction of plastic and its waste treatment infrastructure saturation. It relates to ecology, but it is also a societal issue. While manufacturers are responsible for packaging, consumption patterns are also the responsibility of individuals. And consumption habits die hard. The question arises as to the viability of the consumerist model. Despite the relative inertia of consumers and the weight of traditions, awareness is growing. Initiatives are emerging to reduce the production and consumption of plastic, improve recycling chains, and even reuse waste to build artificial islands.