Ever since the remote village of Shirakawa-go (白川郷) was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995, it has been a top destination in Japan’s Chubu region. Nestled in the lush mountains of Gifu prefecture, the village is famous for its traditional thatched roof houses, about a hundred of which still stand in the hamlet of Ogimachi (荻町).

Shirakawa-go’s 1,600 residents continue to live a traditional way of life that may soon disappear. Take a moment to enjoy the tranquil atmosphere under a thatched roof, and spend the night in the stillness of the mountains, listening to the elements of nature around the crackling fire of a sunken hearth.

Shirakawa-go, an Alpine Village in a Living Landscape

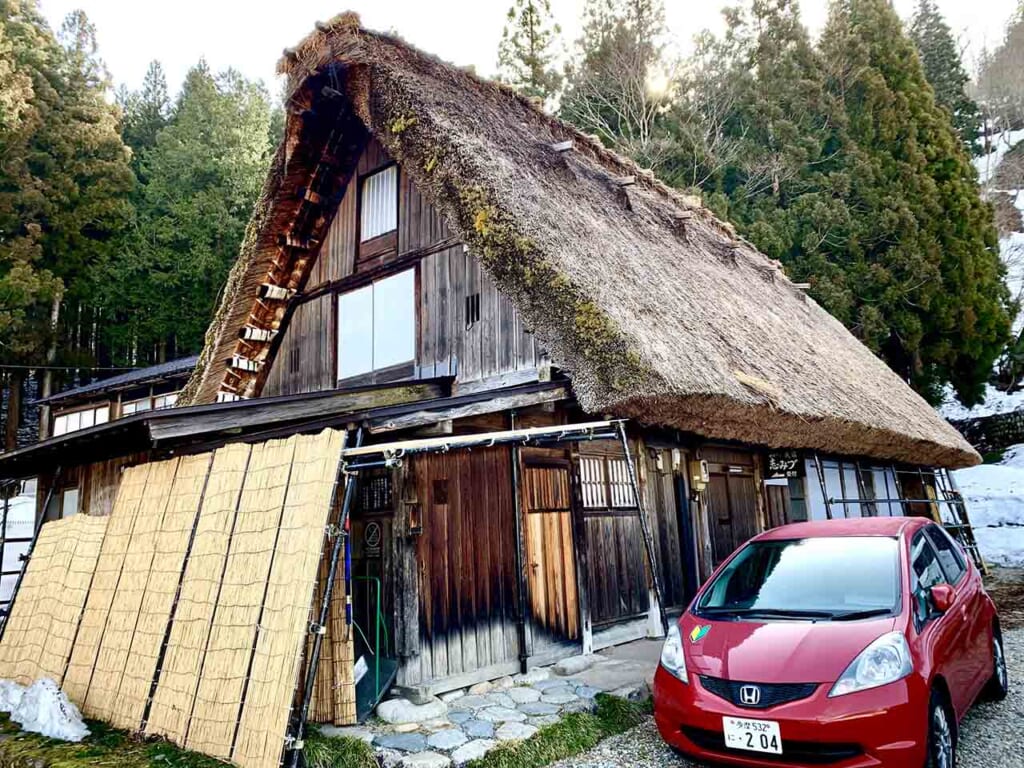

The old houses of Shirakawa-go have thick thatched roofs. Some are shops, guest houses, or traditional craft museums. They stand alongside running streams, a rice granary, and small shrines that compose a charming rural landscape.

In this narrow mountain valley, the houses are built in harmony with nature. Their steeply sloped thatched roofs are oriented east-west to maximize their exposure to sunlight. This is necessary to melt the snow in winter, keep the thatch dry and durable, and protect the houses from strong winds blowing north-south during the typhoon season in Japan.

The Sho River (庄川) runs through Shirakawa-go, and the thatched houses are separated by rice paddies, vegetable gardens and canals. In particular, the canals protect the village from fires and carry water to the households. Rainbow trout live in the canals and help keep the water clean. Walking through the village, I heard nothing but gurgling water and the murmuring breeze.

The farms and thatched houses are built to resist the heavy snowfall of harsh winters in this alpine region. As the silent snow settles on pointed roofs and barren fields, the hamlet transforms into a winter wonderland from a distant era. But Shirakawa-go is marvelous in all four seasons: in spring, it wakes up to the song of cicadas and colorful blossoms; in summer, its vegetation and rice paddies melt into lush greenery; in autumn, the fields and pampas grass take on beige and golden hues.

Despite its natural beauty and deep history, Shirakawa-go is not just an ethnographic museum but an active village with living traditions upheld by its native residents. The riverside community lives harmoniously with the mountains, protected by the sacred Mt. Hakusan at an elevation of 2,700 meters to the west.

Japanese “Gassho” Thatched Roof Architecture Inspired by Praying Hands

Shirakawa-go’s thatched houses are built in the gassho style, which is typical of the Chubu region. Some of these houses are more than 200 years old. Born right here along the Sho river, the traditional gassho-zukuri (合掌造り) architectural style is characterized by the sharply pointed thatched roof, in the form of praying hands (合掌, gassho).

Gassho-zukuri is particularly well adapted to the surrounding environment and mountain climate, with especially harsh winters. It reflects a period when silk was produced in the attic and houses had 3 to 5 floors.

The thatched roofs are designed to support the weight of the snow and prevent it from piling up while also facilitating the flow of rainfall. The thatch itself is almost 80 centimeters thick, and ropes are attached to help clear the snow. Roofs are re-thatched every 30 years.

Another characteristic of gassho-zukuri is the absence of any nails or screws—the beams are tied together using ropes made of straw and vines.

On the ground floor, the irori (traditional Japanese sunken hearth) is used for heating, cooking, and drying clothes. Latticed wooden flooring serves as ventilation, where the heat and smoke from the irori waft up the floors, filling the house with delicious aromas and a black interior. In summer, the smoke also repels insects.

The latticed floors also protect the wood and thatch from humidity, especially during the rainy season (梅雨, tsuyu) between June and July.

Japanese Houses Designed for Raising Silkworms

In the past, the villagers of Shirakawa-go lived mainly from sericulture, as well as the production of ensho (煙硝) for gunpowder. Their property was optimized for silkworm farming, which had the advantage of taking up little space.

Houses were oriented north-south, following the direction of the wind, which provided good ventilation for the cocoons. Silkworms were raised on the top floor, under the main beam, where they not only felt the cool breeze but were exposed to direct sunlight through open windows in the attic.

Traditional Co-living and Co-working in Shirakawa-go

Villagers traditionally lived together in communities where several families (up to 30 people) would reside in a single house. Still today, Shirakawa-go residents naturally work together to maintain the houses (yui) and harvest kaya, the grass used for thatching.

Wada House is a perfect example of gassho-zukuri, built around 1800. It’s also the largest house in the village that is open to the public. Like many villagers at the time, the ancestors of its current owners made a living from the production and trade of ensho. The inside is preserved with furniture and daily artifacts from that period. Sericulture equipment and silk weaving looms are exhibited in the attic.

Wada House

Wada House

TOURIST ATTRACTION- Japan, 〒501-5627 Gifu, Ono District, Shirakawa, Ogimachi, 山越997

- ★★★★☆

A special treat to savor around the irori is zenzai, a traditional dessert soup made with sweet red azuki beans, with mochi and green tea. This is particularly heartwarming in winter, but you can experience it at any time of year at Gassho-zukuri Minkaen (合掌造り民家園).

Shirakawa-go Gassho-Zukuri Minka-en

Shirakawa-go Gassho-Zukuri Minka-en

TOURIST ATTRACTION- 2499 Ogimachi, Shirakawa, Ono District, Gifu 501-5627, Japan

- ★★★★☆

Spend the Night in a World Heritage Site at Shirakawa-Go

By nightfall, as Shirakawa-go’s thatched houses light up one by one, staying overnight in a thatched roof minshuku (民宿) is a truly unforgettable experience. In this Japanese-style homestay, your hosts will introduce you to their own traditional ways of life, including a family dinner prepared with local ingredients around the irori.

By spending the night in the village after all the daytime visitors had left, I could better appreciate Shirakawa-go’s brute charm and true soul. Sitting around the fire, listening to our dinner meat sizzling over the fire in an otherwise silent nightscape, and waking up to the sun rising above the sleeping hamlet, I felt the communion between the villagers and their mountain

environment.

I stayed at Shimizu Inn (民宿 志みづ, Minshuku Shimizu) in Ogimachi. The house itself is almost 200 years old. Its three tatami-floor rooms are positioned around a central room where meals are eaten together around the irori.

For dinner, we tasted the regional specialty of succulent Hida beef, along with local seasonal vegetables. Guests chatted quietly around the hearth, the floor creaked underfoot, the pot sizzled over the fire. By 8 PM, all was silent inside the house.

The courtyard faces west with a view of Mt. Hakusan. In summer, the frogs croak in chorus. In autumn, the mountain is covered in flamboyant red and orange leaves. In winter, you snuggle up to the warmth of the irori’s crackling wood fire.

Practical Information

For more information, visit Shirakawa-go’s official website.

Related articles about Hida:

- Hida, a Historical Valley of Japanese Traditions

- Takayama, an Enduring Landscape of Authentic Japan

- Ecotourism and Beauty Baths in Gero Onsen and Kanayama

- Local Gastronomy in the “Satoyama” of Hida Takayama

How to Get to Shirakawa-go

By bus: Take a Nohi Bus from Takayama (50 minutes), from Kanazawa (1 hour 15 minutes), or from Nagoya (2 hours 45 minutes). Reservations are required.

By car: Japan’s longest tunnel links Takayama to Shirakawa-go in 45 minutes. The 10-kilometer tunnel was inaugurated in 1995, when the historical villages of Shirakawa-go and Gokayama were listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The centuries-old village of Shirakawa-go is a unique place to experience traditional ways of life in the remote mountains of Gifu, where residents continue to honor ancestral customs, techniques and wisdom.

Article sponsored by Hida Regional Tourism Council

Translated by Cherise

Shirakawa-go

Shirakawa-go

ESTABLISHMENT PARK POINT_OF_INTEREST- Ogimachi, Shirakawa, Ono District, Gifu 501-5627, Japan

- ★★★★☆

Shimizu|Shirakawa-go Kayabuki Guest House【Official】

Shimizu|Shirakawa-go Kayabuki Guest House【Official】

LODGING- 2613 Ogimachi, Shirakawa, Ono District, Gifu 501-5627, Japan

- ★★★★☆

No Comments yet!