Weaving Under the Watchful Eyes of Masters

Yuki is a small city in Ibaraki with an impressive history of unique and beautiful arts and crafts. It’s known for unique silk-crafting methods and the presence of Japanese sake breweries. Travelers can easily visit it and its neighboring town Sakuragawa, as well as Mt. Tsukuba, in a single day trip or overnight stay. Its hidden offerings are not easily visible to casual passersby and are therefore all the more rewarding when discovered.

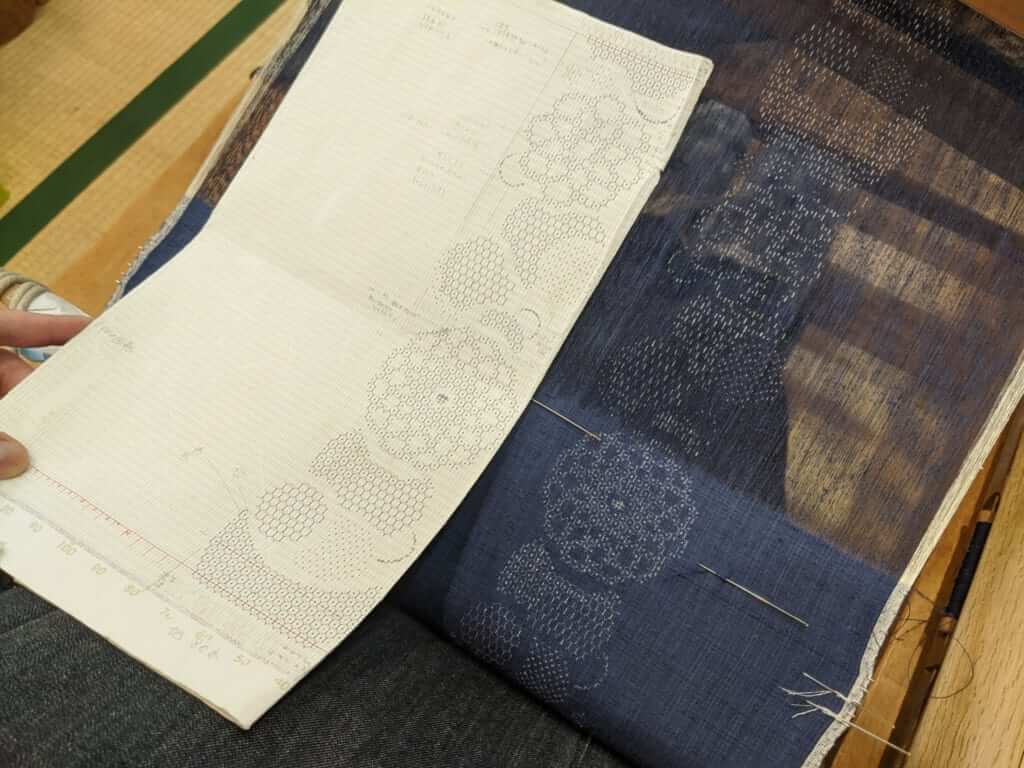

I started this trip headed to the Yuki City Gallery of Traditional Arts and Crafts 結城市伝統工芸館, which is a combination educational center for learning about Yuki’s centuries-old method of silk-making. There are over 40 steps involved in Yuki’s silk making process, of which 3 can be learned at the the gallery: yarn spinning, ground weaving, and knotting. The process, indigenous to Yuki and dubbed Yuki-tsumugi 結城紬, was named a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2010. At the Yuki Information + Communication center, you can rent a kimono or purchase silk products such as scarves and wallets.

Upon entering the gallery I was struck by how streamlined and efficient Yuki-tsumugi seemed. There was no machinery, and no noise at all except the clicks and clacks of wooden looms controlled by the intensely focused craftsmen, and the squeaks of puffy silk being pulled and twisted into individual threads. I was awestruck by how easy the entire process looked in the hands of experts.

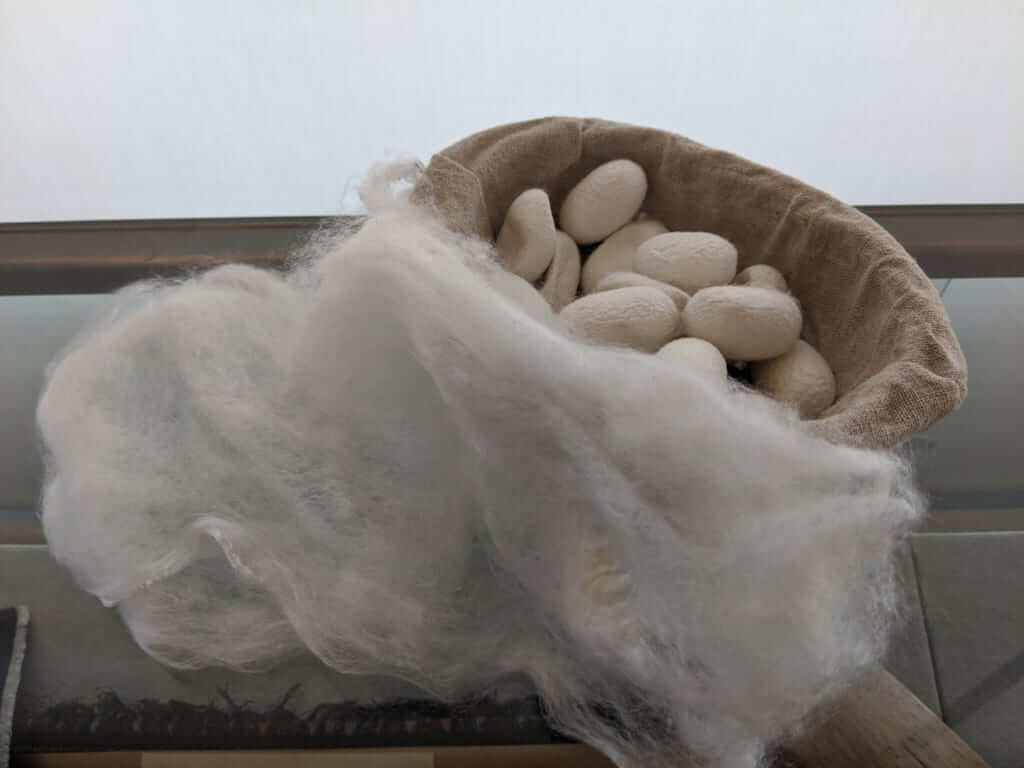

One set of craftsmen sat on looms, and the other set pulled silk into threads. I was told by my guide that, interestingly enough, pulling silk into threads was the more difficult of the two disciplines, and left literally in the hands of the most veteran craftsmen. Because it takes about 34 kilometers of individual threads to make one single piece of fabric used for an item like a kimono, the individuals involved in this step of the process have to demonstrate immense patience. As an educational center, the gallery had actual cocoons from silkworms available to examine, and charts and pictures to help explain the entire process.

I had the chance to take part in this historically venerable craft. I was shown a couple selections of simple designs for square coasters and given the chance to make one myself, by hand, in the Yuki-tsumugi tradition. I sat on a loom, had a belt tied around my back, and another rope tied to one of my feet. The processes of weaving involved first passing a wooden board – with a thread tied around it – through a double layer of thread (with the base color for the coaster) that stretched up to the loom itself. I tapped into place the thread connected to the wooden board, passed it through to the other side of the loom, and then back through – tap, tap – to the other. The gallery’s guide and a master craftsman helped me at every step. It was extremely painstaking, and also physically tiring (even just for a coaster), but once I found a good rhythm I was able to move forward at a nice pace.

In the end, I finished my coaster in about an hour and a half and left with a wonderful memory tucked into a plastic bag, which I’m honestly quite proud of having made. For such a unique experience, it’s worth taking a trip to the gallery and trying your hand at a fantastically detailed craft.

The Diligent Art of Brewing Sake

For my second stop in Yuki, I went to Buyu Brewery, a small Japanese sake distillery and brewery housed in a traditional wooden building called kurazukuri, designed with two layers of walls to prevent fires.

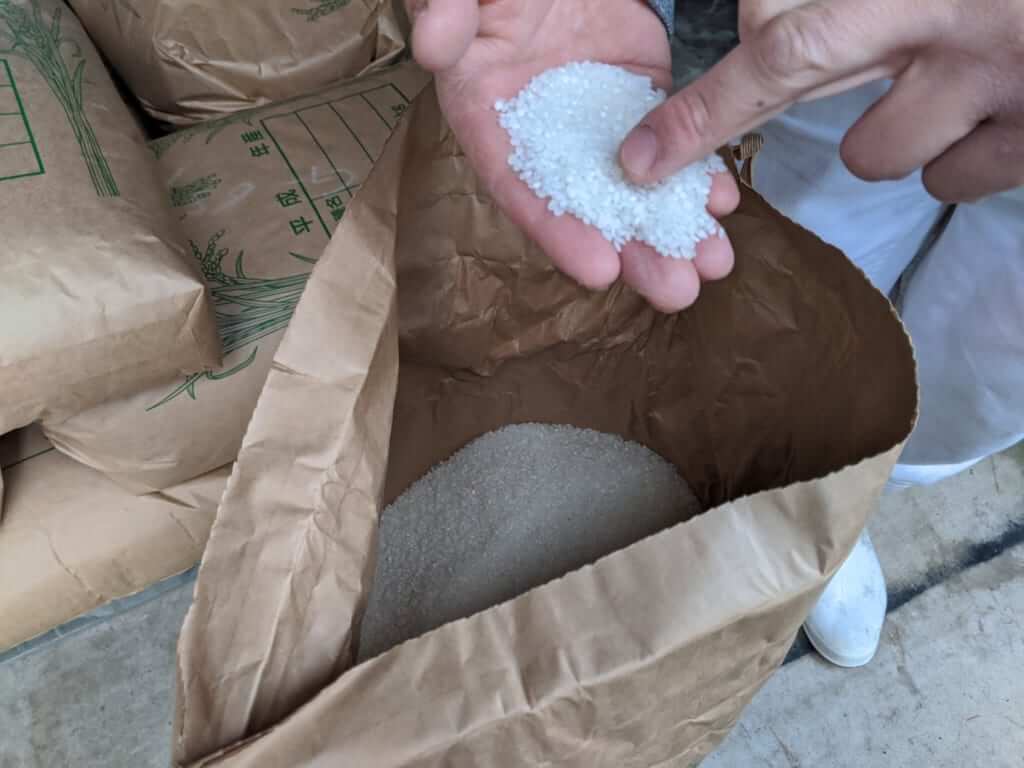

The brewery has tastings and also sells sake directly, and this was the first room I passed into, where various kinds of sake were on sale. I was taken around through the sake brewery by two very knowledgeable employees who explained, in detail, the entire process of making sake from rice to bottle. The first room was piled with sack after sack of rice waiting to be made into sake. This first step is crucial, I was told, because the final form of sake depends almost wholly on the grain of rice (sake rice, as opposed to rice used for eating, has almost zero protein content) and how many times the rice is purified. The more times the rice is refined, the more of the proteins gets removed, and the higher the grade of sake.

The entire facility had to be kept at the same, cool temperature so that the sake brewing goes well. It was chilly as I passed from room to room, indoors and outdoors, but I could tell that the sake-making process was very delicate and couldn’t be disturbed by light, temperature, or external materials such as dirt or microbes. The second chamber, in fact, where bacteria is introduced to ferment the rice, is so sensitive to environmental changes that no one who is not an employee is allowed inside.

The third step of making sake is the rice-purification step, and my guide opened a bag of rice to take a handful and demonstrate minor variations between grains. Larger grains were a sign of a high-quality bag that would go on to produce a finer grade of sake.

The final room in the brewery contained giant fermentation tanks containing what would eventually be sake. The liquid ferments for about a month, then is squeezed, strained and bottled into what can be bought in the store as sake.

Before heading out, I was invited to taste some of the sake that the brewery is known for. Sake, much like wine, can be evaluated based on notes, and is fundamentally dry, sweet, or fruity. The highest grade sake that I tried, which can be bought in a store for about $30 was refreshing and dry enough to taste nearly like water. The second one, called Daiginjo, was sweeter, but also quite excellent. The third one, which was yellow in color, was fruity. I recognized at that point that the sake typically available in convenience stores across Japan was of the “fruity” variety.

The trip to Yuki was educational and enlightening, and I learned not only knowledge, but real, tangible crafts that generations of people have labored to produce and maintain. I felt humbled by the experience and left with a greater appreciation of goods and arts that constitute such a large part of life (textiles and beverages in this case), but by and large remain poorly understood by many in the current age. Yuki was the perfect nexus for learning from true masters about age-old customs that remain otherwise unknown and unseen.

How to Get to Yuki

Tokyo station – Koyama station: about 45 minutes

Koyama station – Higashiyuki station: about 15 minutes

Sponsored by Ibaraki Prefecture

No Comments yet!