A flag represents all that a nation stands for: ideals, culture, history, and the people themselves. All these elements are united under one banner, forming a national entity. As a country with a history as rich as the traditions it has carried on for centuries, Japan and its flag have a unique story to tell, from shining achievements to the darker chapters of its history. In this article, we take a deeper look at Japanese history itself and how this history shaped the iconic flag we know and love today.

Ancient and Medieval Beginnings

The Japanese flag we all know today is commonly referred to as Hinomaru (日の丸, literally meaning “circle of the sun”) or by its official name, Nisshōki (日章旗, “flag of the sun”). Its simple, yet effective design makes it recognizable all over the world, the unmistakable red disc in the center of the white rectangle. Although we immediately associate this flag design with Japan, it has only been in official use for around 150 years. To discover its origins, let’s go even further back in history to see what shaped the modern Japanese flag and the country it represents.

Designs vaguely resembling the modern-day Japanese flag date back to the 8th century, when Emperor Monmu decorated his ceremony hall with a newly designed flag. The design of the Nissho (日章, “the flag with the golden sun”), which he created for the new year celebrations in 701 (first year of the Taihō Era), is said to be the original Hinomaru (日の丸), yet it is unclear whether this flag was the inspiration for any later or modern-day designs. One connecting link between later interpretations of the Hinomaru and the mysterious Nissho is the symbolism of the sun, which has been ingrained into Japanese mythology and religious practise since ancient times.

The next instance of a design similiar to the Hinomaru, according to a theory, was seen in the Genpei War (源平合戦), which took place between 1180 and 1185. This war marked the end of the Heian Period (794 – 1185), the last division of classical Japanese history. The era came to a bloody end when two opposing clans, the Taira and Minamoto Clan, fought over control of Japan. The Taira, which had dominated Japanese politics during the Heian Period, waged war against the Minamoto under a red flag with gold and silver moon circles. This flag, called Nishiki no Mihata (錦の御旗, “honourable brocade flag”) was also the symbol of the Imperial court during the Heian Period. The Minamoto, in opposition to both the Taira and their flag, chose a pure white flag. The war ultimately concluded with the Minamoto assuming control of Japan and establishing the Kamakura Shogunate. Later in history, successive Shoguns of Genji, leader of the Minamoto, used the flag of Shirachikamaru (白地赤丸, “red circle on white background”) as a symbol of national unity. This flag is a combination of both the Minamoto’s and the Taira’s battle flags and believed to be the origin of the Hinomaru design.

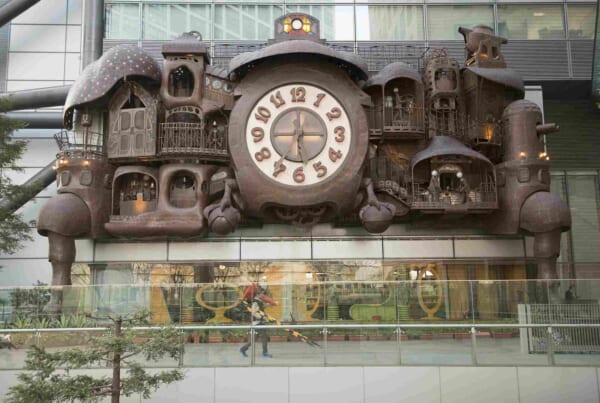

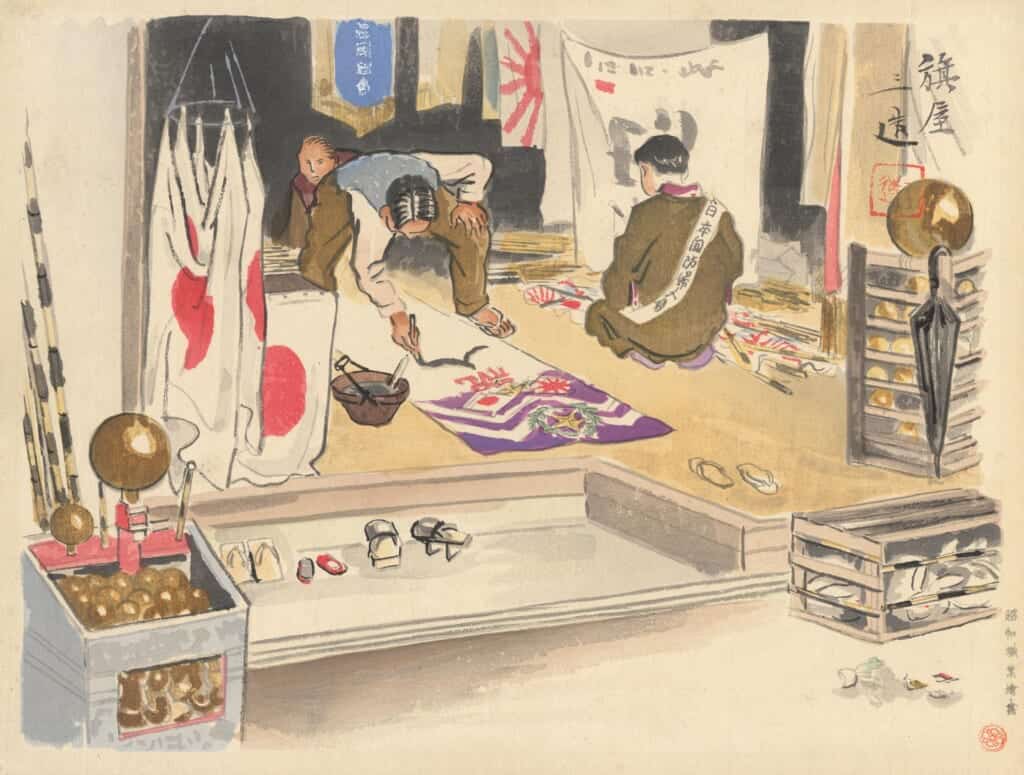

Later, when Japan experienced a new wave of unrest during the Warring States Period (戦国時代, Sengoku Jidai, 1467 – 1615), the sun symbolism was reinterpreted by the war-waging Daimyō, powerful feudal lords of the time. Some of them used the Hinomaru design as their Uma-jirushi (馬印, horse insignia), an enormous flag identifying the Daimyō or an equally important military figure on the battlefield. In addition to red-on-white, the Hinomaru would also be crafted as a gold-on-blue variant, as seen on the far left of the picture below.

During the same era, the fleet of Kuki Yoshitaka, a naval commander under Oda Nobunaga, would also utilize the Hinomaru on his warships. The picture below shows Yoshitaka’s fleet, with the largest of contemporary warships, the Atakebune (安宅船 / 阿武船), going into battle under a Hinomaru.

The Sengoku Period ended with a unified Japan, marking the beginning of the new Edo Period (江戸時代, Edo Jidai, 1603 – 1868). The Tokugawa Shogunate reluctantly opened trade routes to a number of selected nations, such as Holland, China, the USA and Russia. In order to distinguish themselves from foreign vessels, the Shogun ordered Japanese trade ships to raise the Hinomaru. This was the first instance of the Hinomaru being officially used to represent Japan to the rest of the world.

Modern History

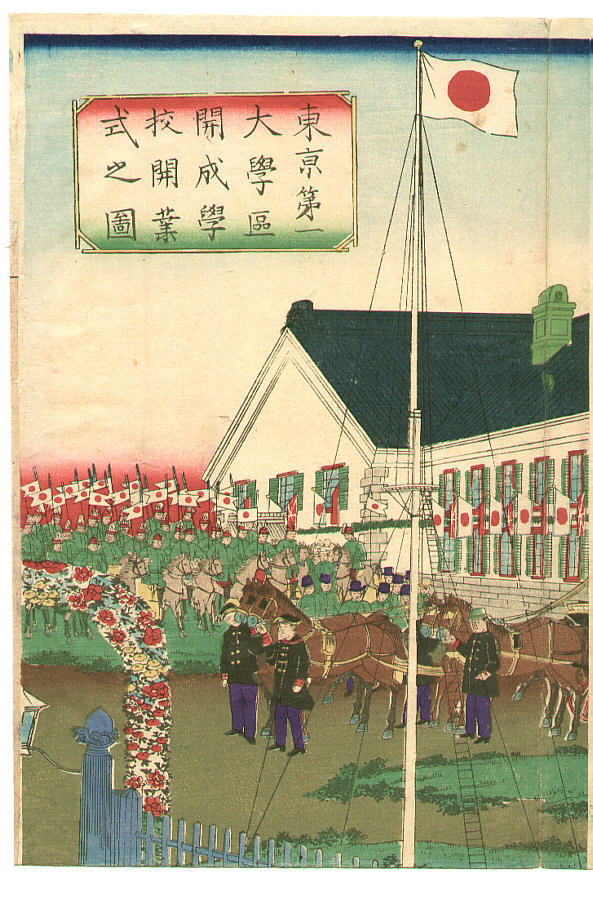

Even though Japan was modernized during the Meiji Restoration (明治維新, Meiji ishin), the idea of a national flag still seemed rather foreign to the Japanese. After all, for the first time in its history, Japan was now a nation. And just like the Daimyō had already used the Hinomaru to identify themselves on medieval battlefields, Japan would now have to identify itself in the world as a new, rising power with a flag of its own. Since it had been used on commercial ships during the late Edo Period, the Hinomaru had already achieved international recognition. Additionally, with its roots deep in Japanese mythology and history, the Meiji government would decide on the Hinomaru to become Japan’s official national flag — as a symbol for the new era ahead and to represent what the country was built upon. Along with the Hinomaru, the national anthem Kimi ga yo (君が代) and the imperial seal had also been made official symbols of the state. The flag was first raised on the grounds of government buildings in the year 1870, Japan started using the Gregorian calendar in 1873.

With Japanese nationalism on the rise, the Hinomaru also gained representation and meaning. After Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese and First Sino-Japanese war, the flag was permanently present at war celebrations and events, contributing to a nationalist sentiment of the general public. Textbooks displayed the flag along with patriotic slogans, teaching children the virtues of being a “good Japanese”. During the Second World War, the flag became a symbol of imperialism in Japanese-occupied areas, such as Manchukoku and the Philippines. Although local flags were still allowed, school children had to sing the Japanese National Anthem during morning ceremonies while a Japanese flag was hoisted.

After Japan’s defeat in World War II and the subsequent occupation by US forces, strict rules were applied to patriotic symbols such as the Hinomaru. In order to hoist the flag, permission from the US military command had to be given first. With Japan’s new constitution coming into effect in 1947, several restriction on the flag were lifted. Two years later, all restrictions were abolished and anyone could raise or display the flag without needing permission.

Because of Japan’s role during World War II, the Hinomaru has often been associated with the country’s militaristic past. Because of this, public display of the flag has decreased since the end of the war, as Japan has adopted a more pacifist stance since then. Nonetheless, when the Law Regarding the National Flag and National Anthem was passed in 1999, the Hinomaru and Kimi ga yo (Japan’s National Anthem) were reinstated as official symbols of Japan. Before then, they were merely de-facto symbols, not stated in legislation as the official state flag and national anthem.

Flag Design

Previous designs and interpretations of the flag have always been inspired by the mythological roots of Japan — the sun, to be more precise. It plays an essential role in Shintō religion as the emperor is said to be a direct descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu. Japan’s nickname, Land of the Rising Sun, has also been in use since the 7th century. It comes to no surprise that the sun was chosen to grace the Japanese national flag, perfectly representing the Land of the Rising Sun.

The colors, shapes and proportions of the Hinomaru are exactly specified. The “sun” at the center is tainted in a color called beni iro ((紅色), which is reminiscent of a crimson-colored sunset one would experience in Japan. TThe diameter of the sun is 3/5th of the flag’s total height, located in the exact center. The background is a plain, yet pure white. The flag as a whole reminds one of the dominance of red and white at Shintō Shrines, emitting the same peaceful aura.

The Rising Sun Flag

Apart from the Hinomaru, there is another flag often associated with Japan, or rather, its military history. The Flag of the Rising Sun (旭日旗, Kyokujitsu-ki) has different meanings for different people, but is often at the center of controversy. The flag is based on the same design as the Hinomaru with additional rays emitting from the sun at the center. Its origins can be traced back to feudal warlords using it during the Edo Period. After the Meiji Restoration, it found new purpose as the official war flag for the Japanese Imperial Army. Shortly after, it was also adopted as the naval ensign for the Imperial Navy. As the flag also represents good fortune, it was and can still be seen on some commercial products, such as the original logo of the Asahi Newspaper. It is also still in use by the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, although it has been slightly modified since World War II. An alternative version is also used by the Japan Self-Defense Forces and Japan Ground Self-Defense Force.

Due to Japan’s imperialistic past, the flag is considered offensive in East Asia, especially in South Korea and China. The flag is directly associated with Japan’s occupation of the countries, as it has also been in use during that time.

Use of the Flag Today

The Hinomaru can mostly be spotted during official ceremonies and national holidays. Of course, it is also raised when welcoming state guests from abroad, such as ministers and presidents. In everyday life, the flag is usually only seen hoisted in front of government buildings, like city halls or ministries. In contrast, they are rarely seen on private buildings, although some people and companies like displaying the flag on public holidays. As it is common in many countries, the flag is lowered to half-staff (半旗, Han-ki) during periods of national mourning, as was the case when the Showa-Emperor passed away in 1989.

Rooted in both legends and history, the Japanese flag is a design that captures the spirit of Japan’s origin as well as its future. It’s a design that is instantly recognizable around the world and has become a symbol of peace even through its sometimes dark history.