Noda is a small city north of Tokyo in Chiba prefecture easily accessible by train from Tokyo and is known as “the city of soy sauce” because of the city’s longstanding relationship with the soy sauce industry. It is the home of Kikkoman, the world’s most recognizable name in Japanese soy sauce (called shoyu 醤油 in Japanese), and a host of historical buildings dotting its downtown. Taken along with its neighboring cities of Matsudo, Kashiwa, and Nagareyama, Noda provides a fantastic opportunity to not only get away from Tokyo for the day, but learn about the history of one of Japan’s most iconic food products.

The World’s Most Renowned Japanese Soy Sauce

My first stop in Noda was The Kikkoman Institute for International Food Culture キッコーマン国際食文化研究センター . Kikkoman is a world-renowned soy sauce brand, famous to the point of likely being the only brand known to many people in the West. Kikkoman’s red-capped soy sauce bottles (and green for low sodium) can be found in any supermarket or Japanese restaurant in the United States, as well as other flavors like teriyaki sauce. In Japan, Kikkoman is equally famous and has led the shoyu market for decades.

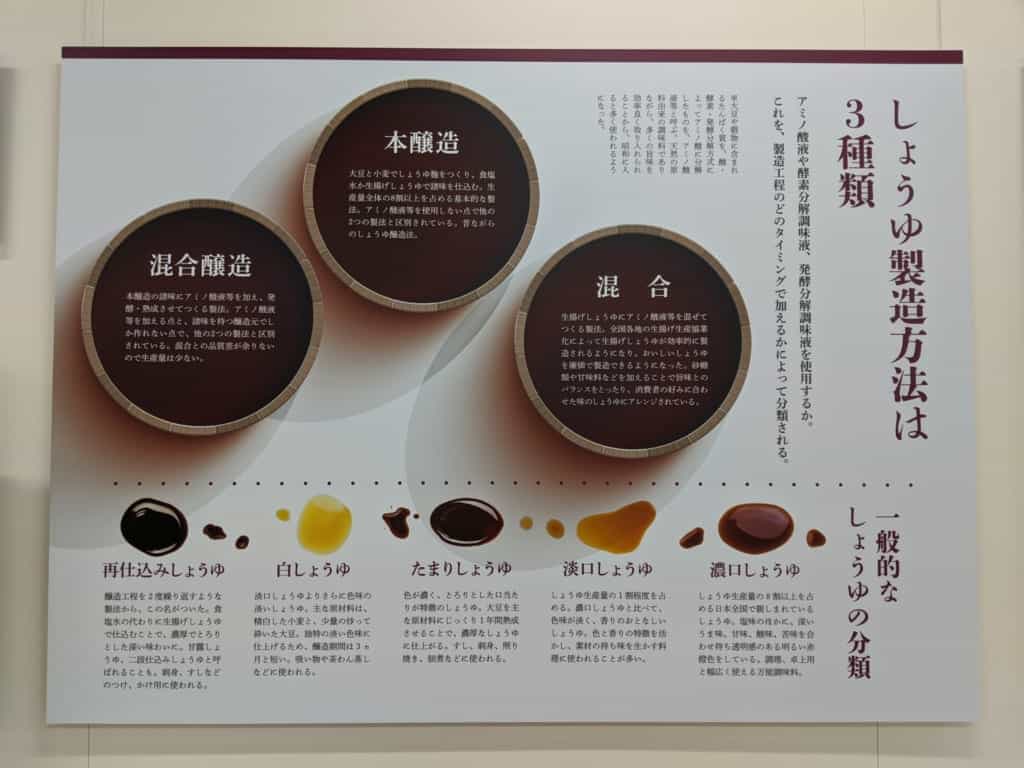

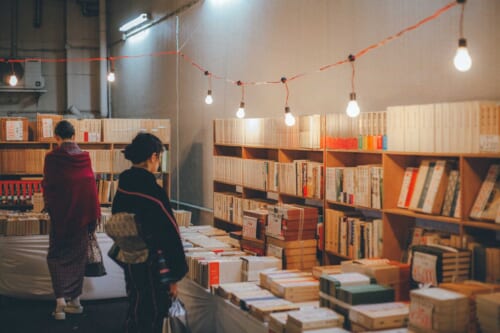

The Kikkoman Institute for International Food Culture is a facility which integrates a library, informational session complete with videos, and information about all things food-related (but especially soy sauce). There are timelines depicting the history of soy sauce dating back hundreds of years, through the founding of Kikkoman in 1917, to the course of modern production trends such as food sourcing. I learned about different grades of shoyu (from super light to super dark) and got the chance to see memorabilia like novelty shoyu bottles, and traditional pots used for transporting soy sauce.

All in all, the institute was extremely interesting, educational, and worth the visit. It’s a celebration of shared, global food culture more than anything else. Admission is free, and the general manager, Kotaro Yamashita, speaks English and is a welcoming wealth of knowledge for any and all visitors.

Hometown Pride: Kinoene Soy Sauce Factory

Next I drove to another soy sauce factory, this one being family-owned for generations: Kinoene キノエネ醤油 . Kinoene shoyu is a smaller, somewhat boutique operation (especially in comparison to Kikkoman), but they’ve still managed to stay strong. I took a tour of the grounds, which are spread out across several groups of buildings, and got some nice photos of the outside of the production facility. I wasn’t allowed inside to see the production first-hand, but the entire tour was still educational enough to get a good sense of the entire operation.

Kinoene’s biggest contribution to the world of soy sauce was also one of the most interesting parts of the tour: white soy sauce. I learned from the factory’s current manager about the intricacies of using white soy sauce, how people tend to overuse it because their broth isn’t getting darker or heavier (no matter how strong the flavor is), and about how it’s definitely Kinoene’s trademark product. Even though Kinoene isn’t as well-known as Kikkoman, they still ship their soy sauce all across Japan, so it’s definitely worth picking up a rarer brand of Japan’s favorite cooking ingredient during your travels (especially the white kind).

The building of Kinoene head office

Downtown Noda at Night

After visiting the Kinoene soy sauce factory, I went back to the area near the Kikkoman institute for a stroll around downtown Noda. It was starting to get dark because of the time of year, but I was still able to see the charm and intrigue of Noda’s streets. Noda is a small town, but one full of history. There are a variety of historical buildings (tatemono) peppered around the area, such as traditional Japanese houses and attached gardens, municipal buildings, and schools, many of which were donated by companies for the cultural enrichment of the area. The Noda is also home to one of the branches of the Tokyo University of Science, so in addition to having a rich, industrial history, the area plays host to a community of young adults who bring their energy and ideas with them.

One such famous tatemono I passed was a bank (closed by the time I got there) that looked like it was pulled directly off the streets of a city like Boston. Such buildings are a rarity in Japan (brick, in fact, is rare enough to warrant attention), and it was surreal to see it in the middle of a suburban street in Japan, lit by night lights. Noda is not extremely out-of-the-way, by any means, but the scene reminded me that harder-to-access areas of Japan contain hidden, unique things that make any journey worthwhile.

At the end of my trip, I left Noda with a greater appreciation of not only the brewing and development of one of Japan’s most treasured and often-used foodstuffs — soy sauce — but how strongly that most common of ingredients holds together an entire region. Noda was a reminder to not take for granted the simplest of products, and to recognize that the present has been built on the backs of every preceding generation. Noda isn’t glamorous, or exciting, but it’s absolutely edifying, much like soy sauce itself.

How to Get to Noda City by Train

Ueno station – Kashiwa station: JR Joban line(Rapid) 32minutes, Kashiwa station – Noda City station: Tobu Urban Park Line: 20 minutes

Akihabara station – Nagareyama Ootakanomori station: Tsukuba Express: 31minutes, Nagareyama Ootakanomori station – Noda City station: Tobu Urban Park Line: 14 minutes

Sponsored by Chiba Prefecture

No Comments yet!