Horimono (彫物) is a little-known term to the rest of the tattoo world but is one of the most used amongst Japanese tattooists. The use of this term emphasizes a deep respect for the practice. Other poetic terms are used in Japan to refer to Japanese tattooing: wabori (和彫) “Japanese carving”, shisei (刺青) “pierce blue”, referring to the blue reflections that sumi ink usually takes as it ages, bunshin (文身), “body decoration” and many others.

However, all these terms have a different connotation from the word Irezumi. This word is frequently used outside of Japan and by Japanese people unfamiliar with this culture. While irezumi is indeed linked to Japanese tattoos, its image and meaning are much more negative.

In this article, we’ll cover the beginnings of Japanese Tattooing, its history, and its evolution over the centuries.

The Origins of Traditional Japanese Tattooing

Irezumi (入れ墨), literally “insert ink” started to become a frequently used term by the Japanese population in 1720. It was on this year, during the Edo period (1603-1868), that tattooing started to be used for punitive purposes on the island. Irezumi was used to mark people who had committed crimes, using symbols that would vary depending on the crime or region. These marks would range from a simple line around the forearm to a kanji (Chinese character) on the forehead.

Thus, Irezumi does not designate the traditional tattoos that we know today. Nowadays, this word can still have a very negative image in Japan, depending on who you are talking to. According to the horishi (彫師), a master tattooist I had the chance to meet, this word still has a pejorative connotation and I quickly understood that it was best for me to not use this term.

A horishi is a master tattooist who practices traditional Japanese tattooing. These professionals are craftspeople and it’s generally inappropriate to think of them as artists. They tend to dislike this word. Just like to designate different styles of Japanese tattooing, there are words to designate people who practice this craft, including bunshinshi (文身師).

This article is dedicated to the traditional Japanese tattoos called horimono, but there are other forms: Face and forearms tattoos of the Ainu women of Hokkaido, the hand tattoos of Okinawa women, as well as traces of tattoos dating back to the Jomon era (13000-400 av. J-C.). While we won’t dive further into these types of tattoos in this article, it feels important to mention them.

Tattooing During the Edo Period (1603-1868)

To understand the evolution of Horimono, we need to go back to its creation during the Edo era. It’s in 1720 that Japanese tattooing referred to as irezumi is put in force by the ruling class. People who committed serious crimes start to become easily recognizable. It’s during this period that Japanese tattooing begins to be perceived in a negative way by the Japanese population.

The practice of tattooing in Japan also developed in other spheres of society. The courtesans of the pleasure districts would sometimes engage in the tattoo culture with some of their appreciated customers. The tattoo was usually a simple black dot on the customers as well as on the courtesans to ink their union. It was a way for these women to have loyal customers and make them come again.

The Influence of Ukiyo-e Art on Japanese Tattoos

Tattooing kept evolving during the Edo era, either out of appeal or to hide the punitive tattoos imposed by the rulers. Its evolution is notably due to ukiyo-e (浮世絵) art, the Japanese woodcut print, one of the most famous forms of traditional Japanese graphic arts. The engravings of Ukiyo-e are filled with different themes: landscapes, kabuki actors (Japanese theaters), shunga (erotic scenes), or yokai (creatures of Japanese folklore). Some of these themes then begin to make their appearance in Japanese tattoos at this time.

The Popularization of Suikoden in Japan

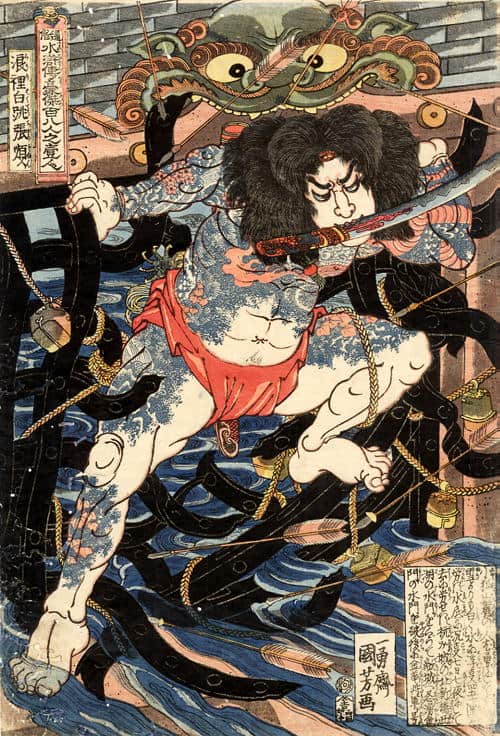

In 1827, tattooing in Japan experienced a turning point in its design and image. It was on this date that the master printmaker Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川 国芳) began a series of work based on The Suikoden.

Suikoden (Water Margin) is a Chinese novel telling the story of 108 outlaws fighting against a corrupt government. The 36 most powerful outlaws are the main heroes of the story, while the remaining 72, less powerful, are their soldiers. This novel can be seen as the Chinese counterpart of Robin Hood. When this novel arrived in Japan, Utagawa Kuniyoshi seized it to stage its protagonists in many heroic woodblock prints.

Since the Shogunate (the military dictatorship during this period) had access to these prints, Utagawa Kuniyoshi paid attention to the details by adding Chinese influences to his prints, especially in the clothes and swords of the protagonists. Otherwise, the government would have seen these illustrations as defiance of the printmaker against the rulers.

To accentuate the legendary and heroic side of these outlaws, Kuniyoshi depicted them with tattoos representing mythological creatures and religious symbols, covering huge parts of their bodies.

It’s at this period that the premises of the Japanese tattooing that we know now appeared. The Japanese working class found the heroic image conveyed in the Suikoden ukiyo-e prints appealing, and many craftsmen at the time began to reproduce these tattoos on their own bodies. From Kuniyoshi, inspired by existing tattoo styles, and the Japanese craftsmen, inspired by Kuniyoshi’s prints, emerged a new form of tattoo style and craftsmanship called Horimono in Japan.

Who Was Getting Tattooed in Japan?

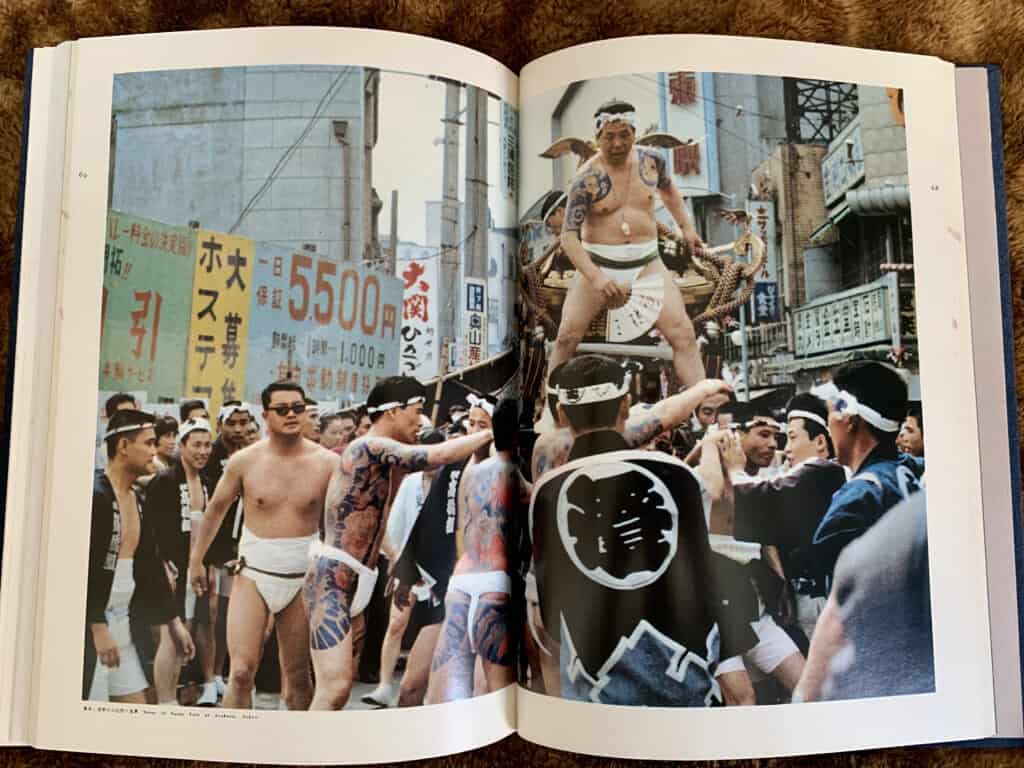

Commonly known as shokunin (職人), meaning craftsperson, were among the most fervent wearers of this new tattoo armor called Horimono. Traditional Japanese tattooing was also found among the civilian firemen of that period, called Shouboushi (消防士). For these trades, tattooing was a form of belonging as well as spiritual protection against flames. Indeed, fires were common in the city of Edo (former name of Tokyo), which was mainly made of wooden constructions. It’s the reason why representations related to water were common at the time. Couriers called hikyaku (飛脚) would cross the cities to deliver messages often dressed only in a loincloth. Tattooing thus became another way of dressing. Another group of people at this period adopted Horimono as a sign of belonging — the kyoukaku (侠客), street knights acting in organized gangs to protect the weak against thugs and the government; the ancestors of Yakuza. The latter also descended from bakuto (gambling managers) and tekiya (street vendors).

The common point between all these social categories is their class difference with the samurai. Samurai saw tattooing as a barbaric practice and considered themselves too highly ranked to get tattoed. Contrary to these high-ranking warriors, craftsmen were not allowed to commit Seppuku (Japanese samurai’s suicide ritual) and saw Horimono tattooing as a way to prove their bravery. We can see here the notion of rebellion against the power in place, which is also present in the Suikoden.

Horimono during the Edo period was a common practice, not taboo, no did anybody attempt to hide it. During that period, tattoos were done entirely by hand using bamboo rods and needles. This technique is called tebori (手彫り) “hand carving.” The only available colors were sumi (墨, Japanese black ink) and vermilion pigment. During this time, the craft would continue to evolve in form and precision until the abolition of the Shogunate, and the entry into the Meiji era.

Tattooing During Meiji Era (1868-1912)

The beginning of the Meiji era put an end to Japan’s isolation, following the end of the Sakoku (鎖国) (from 1633 to 1853), a period during which the Island was closed to the rest of the world. As Japan started to open up, the government was concerned about the image it was sending to other countries around the globe. In order to preserve its image, the country’s authorities decided to put an end to the practice of punitive tattooing (Irezumi) in 1870 and forbade the practice of Horimono in 1872, for fear of sending a barbaric image to Westerners. This ban forced Japanese tattooing to go underground. Even as the culture became marginalized, it did not disappear, and the culture of Horimono among the passionate Japanese remained intact. As soon as this law was passed, the horishi were forced to hide from the authorities with false business signs to continue to practice their profession in peace.

During this period, Horimono became a rare sight and hidden under the kimono. Ironically, on the other side of the world, foreigners started to take interest in this new culture of Japanese tattooing, especially sailors. The popularity of Horimono eventually reached the British royalty, when Prince George, who would become King George V, gets a dragon and tiger tattooed by a horishi during his stay in Japan in 1881.

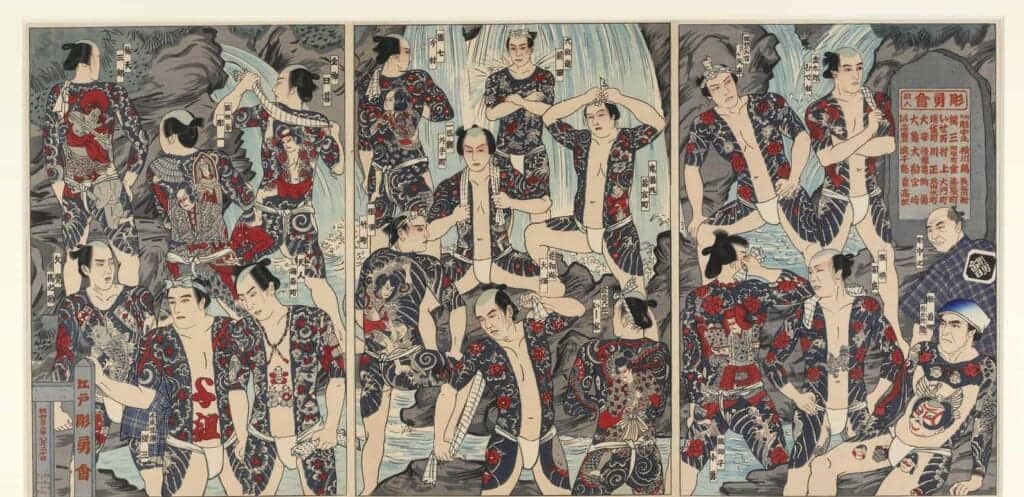

The Edo Choyukai Group

It was during this period, more than 140 years ago, that a significant group for Japanese tattoo culture was formed: the Kanda Choyukai (神田彫勇會). Kanda was the town’s name of customers who founded this group, but as the number of customers began to increase, the organization took the name of Edo Choyukai (江戸彫勇会). The Edo Choyukai was an assembly of people being tattoed by Horishi Horiuno I (初代彫宇之). They kept this culture alive to a point that this group of horimono enthusiasts still exist today. During all these years of existence, the members of the Edo Choyukai will be the customers of Horiuno I, then Horiuno II, as well as Horiuno III. Every year, its member gather at the Shinto shrine Oyama Afuri (大山阿夫利神社) on Mount Oyama, between Mount Fuji and Tokyo, in Kanagawa prefecture. There, Choyukai members participate in a religious ceremony in which they will, among other things, purify themselves under a waterfall and show their tattoos to the gods, before praying within the shrine grounds. The priests who lead the ceremonies and live in the shrine have been welcoming the Edo Choyukai for generations. They understand the spiritual essence of this craft and its importance in Japanese culture and history.

This information comes from a horishi in Tokyo with whom I had the chance to talk.

The Evolution of Tattooing in Japan During Showa Era (1926-1989)

Horimono will undergo great changes starting from the Showa era. Some will be positive, and others will change the very image of the craft.

The American Influence on Japanese Tattoos

After World War II, the Americans settled in Japan and dictated their rule for several years. Among the laws that would be passed under American pressure, the Japanese government was forced to lift the prohibition of tattooing in 1948. Still, the negative image of tattoos will persisted in the eyes of the Japanese population.

The Role of Horigoro and Horihide

After the war, many American soldiers with tattoos were stationed in Japan. Their presence on the island played a role in the evolution of the tattoo profession. Between the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s, two horishi will participate in a revolution of Horimono.

The first one is Horigoro I (初代目彫五郎). He encountered an American soldier who owned an electric tattoo machine, which led him to build his own machines inspired by the soldier. This is how the first Japanese tattoo machines appeared.

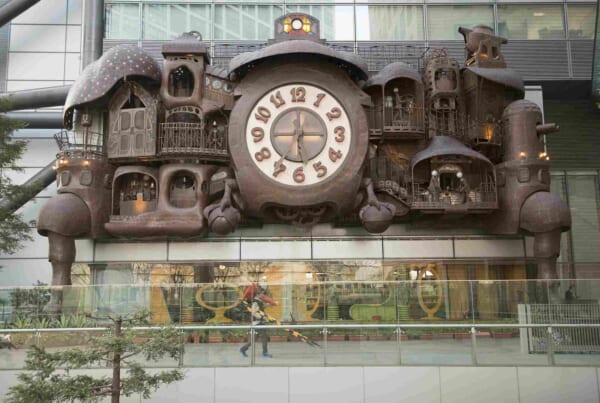

The second horishi who played a very important role in Japanese tattooing is Horihide (初代岐阜彫秀). Horihide is the first Japanese tattooist to establish a connection with an American tattooist. It was during a visit to Senso-ji (浅草寺) temple in Asakusa (浅草), where he met three American soldiers with tattoos on their arms. These colorful tattoos were created with machines, not by hand. Horihide managed to get the business card of their tattoo artist living in Hawaii, who was none other than Sailor Jerry, a tattoo legend in the United States. Horihide began a letter-writing conversation with Sailor Jerry that lasted for four years before he went to Hawaii. Sailor Jerry was interested in Japanese imagery, while Horihide was interested in getting all the colours he could to bring back to Japan. Sailor Jerry also taught Horihide how to tattoo with a machine. When he left, Sailor Jerry gave him colours and tattoo machines as a gift.

Before this meeting, Japanese tattooing was only made with sumi and vermilion pigment. Back in the day, this pigment was a problem. Even after boiling, treating, and removing the mercury from the mixture, it gave strong fevers for one or two days after being inserted into the skin.

With these new colours in hand and Horihide came back to Japan, the Japanese tattoo industry transformed. When he explained which American company to buy from, colours and machines spread rapidly throughout the country.

This information about Horihide comes from the book Wabori Traditional Japanese Tattoo, which gathers interviews with many horishi, including Horihide.

Why is Tattooing Associated with the Yakuza ?

Between 1960 and 1970, the image of tattooing in Japan was stained once again. During this period, the proliferation of yakuza movies stormed the Japanese cinema industry, in particular those of the Toei production company. In these films, yakuza are always depicted on-screen wearing Japanese tattoos. This phenomenon has greatly led to the connotation we know today.

Moreover, in the years 1980-1990, the activity of yakuza organizations became more and more intense. In response, the Japanese government passed an anti-gang law on March 1, 1992, in order to dismantle many syndicates. The number of yakuza has drastically dropped from about 180,000 members at its peak in the 1960s, to 28,000 members at the end of 2019.

It’s at this period that the population starts to forbid access of their business to yakuza, especially onsen hot spring businesses. For fear of attracting the wrath of the mafia, the onsen owners simply forbade the entrance to tattooed people. It’s important to know that access to sento (銭湯, public bath) has never and still does not forbid tattoos since not all Japanese homes have a bathroom and the sento was considered a public necessity.

From then on, challenges continue to grow start for tattooed people in Japan. Tattooed persons were forbidden to enter onsen or open bank accounts, and became impossible to find a job. This stigma also affects women, so much so that some tattoo artists refuse to tattoo them for fear of the complications that could arise in their lives, and women with traditional Japanese tattoos on their bodies are all the rarer. From this point on, only the Japanese passionate about this tattoo culture and the members of the syndicate carry on the Horimono tradition. However, 30 years later, the tradition persists, and the number of practicing horishi doesn’t seem to be fading, nor the number of customers. At each visit to a sento, it is possible to meet Japanese people proudly wearing their tattoos. The message of the Suikoden heroes is still present. In spite of demonization by the government and a rather negative public opinion towards Horimono, the culture persists and seems to go forward.

The Image of Japanese Tattooing in the Rest of the World

Contrary to what happened inside Japan in the 1990s, Horimono became more and more popular in the tattoo world around the globe. It’s in the years 2000-2010 that its popularity explodes. In Europe, in the United States, and in South America, many tattooists start to specialize in traditional Japanese tattooing. Nowadays, Horimono has never been so popular, both among tattooists and clients. Japanese tattooing may have become popular in the west, but being able to admire these massive tattoos is not an easy thing.

Understanding Horimono

Understanding the entirety of Horimono is a complex thing. To understand this craft, it is important to be familiar with Japanese culture. Talking as much as possible with the Japanese people, with a horishi if you have the chance to meet one, studying Ukiyo-e, visiting museums, or going to temples and shrines. All of these are necessary to get a glimpse of the complexity of Horimono. Few foreigners, and even Japanese, are able to understand and apply all the rules that govern this craft. Tattooists managed to reach this understanding through hard work and patience. The study of Japanese tattooing is a vast subject, which can last a lifetime.

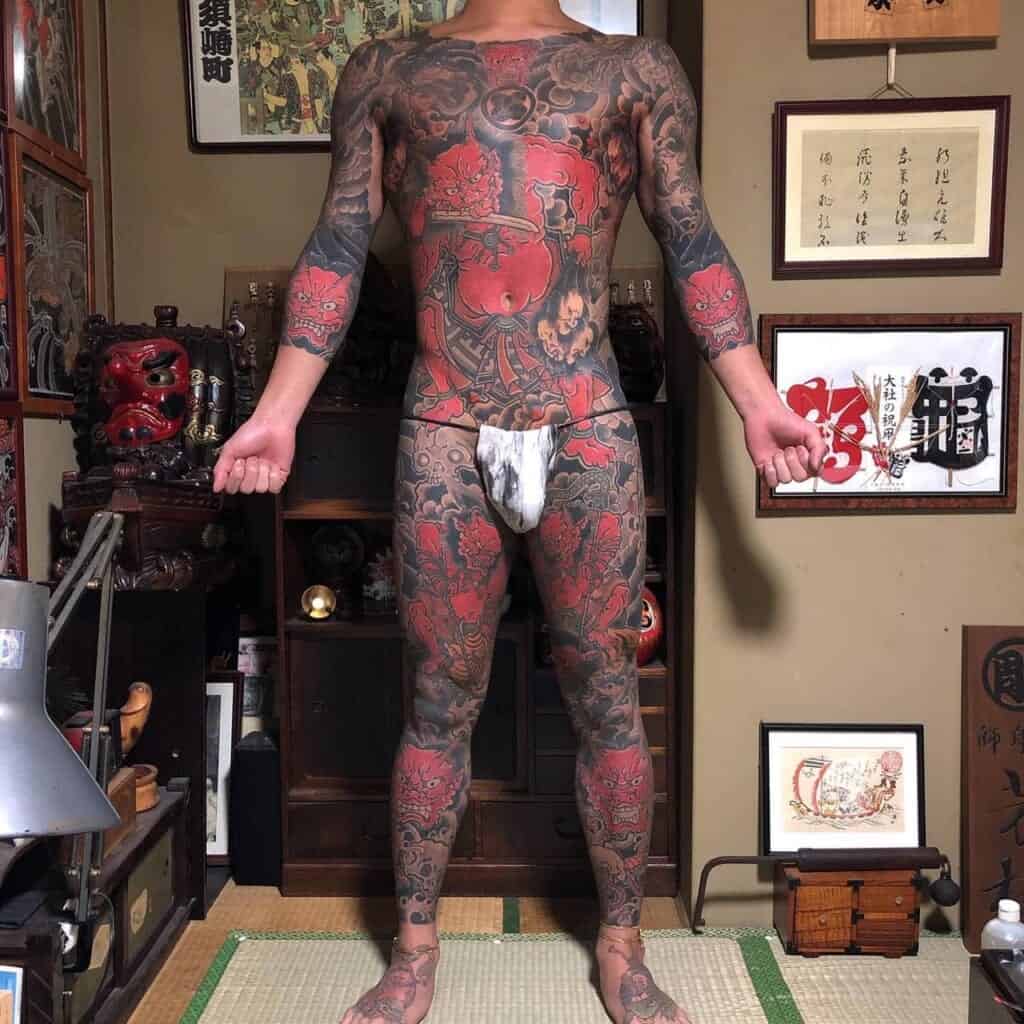

Horimono is a long and painful process, where patience, passion, and determination are key to complete one’s armour. Gaman (我慢 / がまん), or “patience” is actually another synonym used to describe a Horimono. It takes between 200 and 300 to complete a full-body tattoo, from shoulders to ankles. Even after 120 hours of tattooing, the completion of the work still seems far away. The duration also depends on the tool used, a machine will draw the lines much faster than tebori (hand carving) but will insert colours into the skin much faster. Each tattooist works with a different style and speed. It is important to consider all of these details before taking on this challenge. After all the adventures and encounters that a Horimono brought me, I can only be thankful to be in Japan and see with my own eyes what very few people have the chance to experience in their lives.

I want to thank Houryu for sharing his knowledge with me and for allowing me to use the photos of his work.

Hi,

I had a lovely read!

Thank you for writing beautifully and researching the culture behind Horimono.

I’m Japanese myself and thinking of getting a tattoo soon but of course my mother is against it.. but reading this I also understand her perspective and her outlook since she was born and raised in Japan.

I really do wish I see a change in outlook on Horimono and how it doesn’t always represent uncleanliness or something impure and is seen as a spiritual practise, to connect with your body and to express yourself.

Thank you once again.

Izumi