Just outside the crowds of Kyoto city is a world of serene nature, vibrant culture, and deep history that you probably have never heard of before. Oita Prefecture, known mainly for its abundant onsen hot springs, is another area like Kyoto, rich in nature and history. We have carefully selected less crowded destinations in both of these fascinating areas of Japan and will cover them in a series of nine articles: “Travel like a Kyoto and Oita native to experience nature and traditional culture.”

The samurai period in Japan lasted for over 700 years from the 1100s until the abolition of the samurai class in the 1870s. During this period, master swordsmiths in Kyoto and around Japan were in a literal arms race to produce ever more effective swords. Advanced, high-quality swords gave a definite advantage to samurai when fighting, so pushing forward and refining the production processes was a high priority. Swords had to balance strength with durability — if a sword is too hard it is easily broken, but to fulfill its purpose it needs to be able to cut effectively. So the swordsmiths developed techniques to make the cutting blade very hard, and the rest of the core of the sword more robust. This combination created a very practical sword, but once swordsmiths perfected this balance, the focus then shifted to crafting a beautiful object.

Kyoto Swordsmith Masahiro

Yuya Nakanishi is one of the few active swordsmiths in Kyoto Prefecture, and his love of everything to do with swords and the culture that produced them is unmistakable. Nakanishi-san trained in Fukushima Prefecture for seven years to attain the skills, passed down through generations of master swordsmiths, to be able to produce his own swords. It takes him one week to produce the blade of a sword, and he has a list of orders keeping him busy for an entire year.

Master swordsmith Yuya Nakanishi assesses a samurai sword

Today, swords are seen as relics of a bygone era, but in their time they were a cutting edge, continuously evolving product, similar to how we see smartphones now. A phone from ten years ago may still technically work, but compared to the latest models the functionality is considered antiquated, and swords were no different. While it is quite rare to see a sword now, during the samurai period they were extremely common, with even farmers or labourers keeping a sword at home as a talisman to ward off evils such as illness. People would compare their sword to those owned by others almost as a status symbol — not unlike a designer bag or checking what model smartphone someone carries — so the skill of the swordsmith to craft what was seen at the time as a perfect sword was paramount.

Although the idea of a perfect sword changed over time, swordsmiths ended up focusing on three aspects of the sword in particular, with the most important being the ‘hamon’, the pattern or line between the hardened cutting edge and the core of the sword that appears when the edge is hardened. When an expert looks at this hamon, they can tell exactly where the sword was made, as each area had their own preferences. For example, samurai in Kyoto, coming from an aristocratic culture, liked the line to be elegantly straight, but other areas preferred a more natural, harmonious, aesthetic.

Once we had learned about these different qualities of sword production, Nakanishi-san took us to his workshop where we could see him working on the different sword production processes. First was the folding of the steel. The steel is generally folded ten times to squeeze out the impurities that can be oxidized. As he works alone, he uses a machine that was handed down to him by his master — it flattens the steel so it is able to be folded.

Yuya Nakanishi quenches the blade to produce a strong cutting edge

Next, he demonstrated quenching the steel blade which must be done in darkness. Quenching is the process of dipping the steel in water to rapidly cool it which in turn makes it stronger. In the past these processes, and quenching in particular, were highly guarded secrets as they were the key to producing an effective blade. Nakanishi-san told us a tongue-in-cheek story to illustrate this, explained by a swordsmith in the distant past. “When quenching a sword, the temperature of the water is extremely important, so if a master swordsmith saw a trainee slyly checking the temperature of the water with their finger they would instantly cut off the trainee’s hand, as they may be a spy. But, even if the hand of the trainee has been removed and they are in great pain, they might still remember the temperature of the water in their head — so that was the next thing that had to be removed.”

Once the blade is completed, it is sent to a polisher who will work on the blade to reveal the hamon, and the production process continues until the sword is completed three months later.

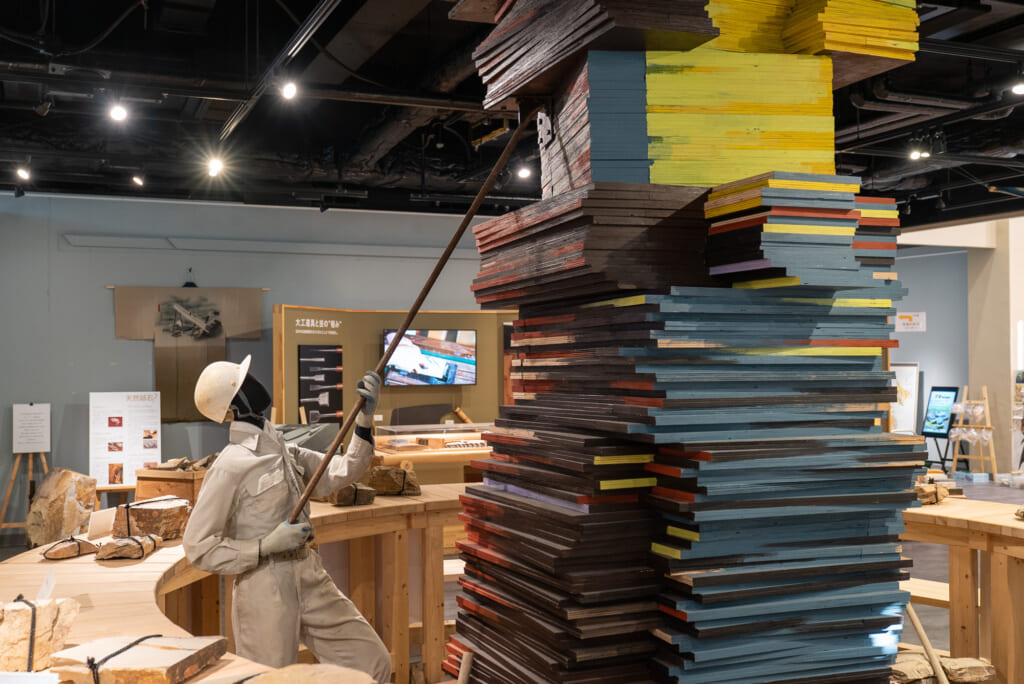

Natural Whetstone and Hone Museum

Kameoka city in Kyoto Prefecture was famous for producing whetstones used in the polishing of Japanese samurai swords, and master sword polishers use various whetstones with about eight grades of grit to end up with a perfectly sharpened blade. The Natural Whetstone and Hone Museum is devoted to keeping this process — and this unique history of Kameoka city — alive, by exhibiting natural whetstones from the Kameoka area and also around the world.

Taisei Ueno is the founder of the Natural Whetstone and Hone Museum which was set up in cooperation with Kameoka city. Ueno-san remembers watching his father and grandfather sharpening their blades using whetstones, and this interest in whetstones stayed with him. The museum has rooms full of whetstones of various grades and ages, as well as detailed information about whetstone quarry locations and historical artefacts. There are sections focusing on whetstones used in sword polishing, kitchen knife polishing, and the polishing of carpenters tools. As well as the historical aspects, visitors can also learn how to sharpen blades, make their own whetstones, or even take one home. This unique museum would be of significant interest to chefs and others who work with whetstones on a daily basis.

Heki-tei — Fine Dining in a Samurai Residence

The Heki-tei restaurant in Kameoka city is a 20-minute drive from the Natural Whetstone and Hone Museum, and ties in perfectly with a samurai related day trip around Kyoto Prefecture. This samurai residence dates back over 300 years, and the Heki family have been in the residence and run the restaurant for the majority of that, over 200 years. The residence and garden are impeccably maintained, and there are historically valuable artworks and artefacts adorning the walls and rooms.

The lunch also has a samurai connection. Composed of six dishes, the centerpiece is called a ‘busho samurai meal’, and is a red miso nabe dish with vegetables and namafu — a type of wheat-based gluten. This meal is a reproduction of one served by the wife of the famous warlord Akechi Mitsuhide when he entertained other warlords at her home. Mitsuhide is widely remembered for double-crossing the famous daimyo Oda Nobunaga, a brutal and powerful figure in the Sengoku period (1500s), by arranging an army of 13,000 soldiers to assassinate him.

Staying in the Kyoto Countryside at The Fairfield by Marriott Kyoto Kyotamba

As you are driving around the rural areas of Kyoto Prefecture, you should take advantage of the fact that you will be visiting areas steeped in history, and instead of rushing back to a hotel in Kyoto city, stay a little longer to explore them more thoroughly. Just 30 minutes by car from Kameoka city, The Fairfield by Marriott Kyoto Kyotamba hotel has been designed with this in mind.

There are co-working space facilities so you can catch up on your emails in the lounge, and the rooms have been designed to be comfortable the needs of Japanese guests and international travellers alike, with higher beds and a large luxurious shower room. To encourage travellers to support the local businesses instead of just staying in the hotel for meals, there are no restaurant facilities, but right next door is the Kyotamba Ajimu no Sato roadside rest stop. This rest stop features a large selection of local Tamba plateau produce including the region’s specialties — chestnuts and black soybeans.

As well as a large shop selling locally made food, the rest stop also has a large marquee outside for markets and events, an information centre so you can find out about everything that is going on in the area, and Restaurant Bochi, serving up delicious meals using seasonal ingredients and the local famous black beans.

Visit Kyoto and Kyushu In One Trip By a Japan Cruise

A perfect complement to touring the countryside of Kyoto is a trip to Japan’s southwest island of Kyushu, also renowned for its natural beauty and traditional culture. Fortunately, reaching Kyushu from the Kansai region could not be easier using the Sunflower Ferry, an overnight ferry service from Osaka Port. Relax aboard this mini cruise in Japan, over the scenic and calm Seto Inland Sea, arriving at the city of Beppu as dawn breaks over Kyushu. For more information about the Sunflower Ferry, be sure to read the article about my experience.

More About Exploring Kyoto and Oita

To learn more about rural Kyoto and Oita prefectures, please continue to read the other articles in our series.

- Enjoy The Autumn Colors Outside of Kyoto City

- Experience Uji Green Tea at a Tea Farm near Kyoto

- Kayabuki: The Tradition of Thatched Roof Houses in Japan Near Kyoto

- From Kyoto to Kyushu: A Mini Cruise on Japan’s Seto Inland Sea

- The Ancient Japanese Culture and Traditions of Oita Prefecture

- The natural beauty of Kyushu: Oita Prefecture

- The Best of Oita: Usa Jingu Shrine, Beppu Jigoku and Chinetsu Ryori

- Unexpected Luxury Awaits You in World-Class Accommodations, Onsen, and Cuisine in Beppu

This article is sponsored by Kinki Transportation Bureau, Kyoto Prefecture and Oita Prefecture.

No Comments yet!