Just outside the crowds of Kyoto city is a world of serene nature, vibrant culture, and deep history that you probably have never heard of before. Oita Prefecture, known mainly for its abundant onsen hot springs, is another area like Kyoto, rich in nature and history. We have carefully selected less crowded destinations in both of these fascinating areas of Japan and will cover them in a series of nine articles: “Travel like a Kyoto and Oita native to experience nature and traditional culture.”

“It is easy to get lost in the winding streets around the site of the Usuki Castle,” our translator explained. This was not accidental, but by design, to make it harder for enemy samurai forces in the Edo Period to mount an attack on the castle. As if on cue, a local shopkeeper listening nearby stepped out of his shop to explain how a famous spear-wielding warrior had defeated four swordsmen in one fight on the street we were standing on. Legend and tradition run deep in this city, but it doesn’t take much to bring them to the surface.

Usuki is a city of roughly 40,000 bordering Oita city on the eastern coast of Kyushu. Though it is perhaps best known as a castle town from the Edo era and the landing site of William Adams (the English pilot on who’s life the novel “Shogun” was based) in 1600, Usuki has a much longer history rooted in Buddhism dating back to the 12th century.

The 1,000-Year-Old Usuki Stone Buddhas Pre-Date Written Japanese History

In a small valley, the Usuki Sekibutsu Stone Buddhas 臼杵石仏 have stood for about 1,000 years, carved into the soft volcanic rock deposited here from an ancient eruption of Mt. Aso in neighboring Kumamoto Prefecture. Among the stone Buddhas there is a statue of Nyorai (如来), which is considered to be the best in Japan. There are four groups of carvings, more than 61 statues in total, though some of them have been severely damaged by the elements over the centuries.

Construction of the Stone Buddhas is believed to have been done from around 1180, the end of the Heian period, to the late Kamakura period, which lasted until 1333. Because this period was well before Japanese written history, they can only be estimated, but there are good reasons behind the estimates. What clues did the Stone Buddhas provide to reveal the date of their creation?

The location of the statues on the west side of Mangetsuji Temple provides the biggest clue. The West was believed to be the direction of “the Pure Land (極楽浄土, Gokuraku Jodo),” the heaven, in other religions, for the sect known as Jodo Bukkyo (Pure Land Buddhism) in Japan. This sect was not introduced into Japan until very late in the Heian Period. The prominent Stone Buddhafixes his gaze on Mangetsuji Temple on the east side of the valley as if he is watching over it.

The monks of Mangetsu Temple were charged with maintaining the statues, but when Mangetsu changed its affiliation to another Buddhist sect, that responsibility was no longer carried out. Eventually, the city took over the maintenance and restoration of these precious works of art and helped further when they were designated as National Treasures in 1995.

Based on the statues’ appearances, a master craftsman from Kyoto and Nara, was likely responsible for their creation, though not a local one. It is believed that local government leaders curried favor with a powerful temple in Kyoto, then Japan’s capital, who dispatched the artist to Usuki. The malleability of the lava rock the statues are carved from enabled the artist to create high levels of detail in the pieces, but also made them highly susceptible to erosion. Currently, wooden structures were constructed over the clusters to help protect stone Buddhas, and care is taken not to allow moss to grow on some of the pieces.

I expected the Usuki Stone Buddhas to be a place of solemn reverence, but in fact, it is a peaceful place where the beauty of nature fuses with ancient spirituality. Some of the stone Buddhas’ faces are even childlike and welcoming, as if inviting you not to take them too seriously. For history buffs, it is certainly awe-inspiring to stand before these beautiful works of art that have guarded over the valley for nearly a millennium.

My lesson in Buddhism wasn’t finished for the day, as we drove back to the twisting streets of the Usuki Castle area to sample a taste of ancient Buddhist tradition, shojin ryori.

Shojin Ryori: Vegan Delicacies Prepared By a Buddhist Priest

Shojin ryori can be explained simply as the food eaten by Buddhist monks and is completely vegan (free of any animal ingredients.) But shojin ryori is much more complex than that, with monk-chefs studying for years learning how to extract flavors, create textures, and present dishes that are as beautiful as they are delicious.

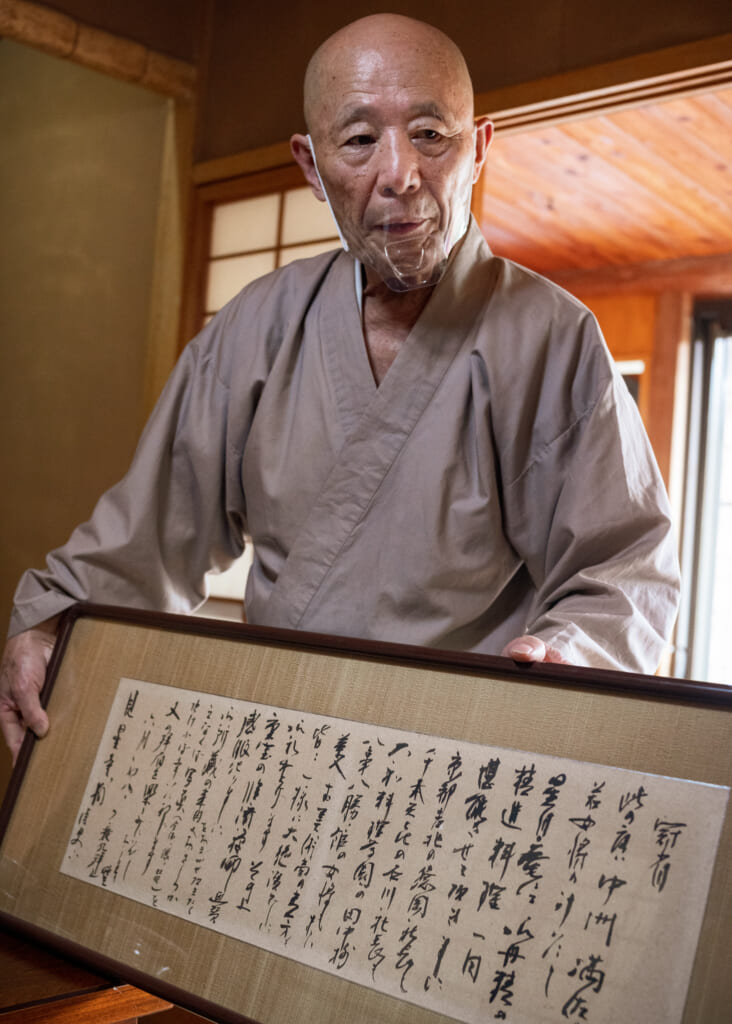

Ando-san, the 80-year-old chief priest who runs Seigetsuan restaurant, is as spry as ever, personally bringing dishes to our table despite the presence of serving staff. It is he who spends 90 minutes each day grinding the sesame by hand to create his signature sesame tofu, a creamy masterpiece that must be tasted to be fully appreciated. It was Ando-san who toiled for years under the master who taught him how to make the famous umami-laden kelp dashi of Seigetsuan before finally being allowed to make it unsupervised. And in the presence of this incredible yet humble chef, we sampled his creations while he patiently described the details of making them.

In the spirit of kaiseki, the entire vegetarian meal consists of small dishes organized around a seasonal theme. In November, the theme was autumn, with elements of nature like maple and ginkgo leaves and pine needles used to enhance the meal’s appearance. Vegetables were cut into maple leaf shapes and potato purees formed into the shapes of chrysanthemum blossoms. As we enjoyed the meal with all of our senses, Ando-san would casually mention how certain pieces of serving ware were actually works of art in their own rights.

Gluten plays an important role in shojin ryori, as it can be made into foods with textures that are similar to meat. However, the art of creating these gluten-based dishes is an art in itself, one that Ando-san has clearly mastered. Anything in my meal that I could not recognize as a vegetable was almost certainly some unique creation made from gluten and flavored in various creative ways.

Seigetsuan is set in an old Japanese home, and you may feel as if you are indeed a guest in someone’s house as you eat your meal. Besides the master, the rest of the staff is friendly and attentive and rarely more than just a moment away. The house is full of beautiful pieces of art collected over the decades and sometimes displayed haphazardly: hanging scrolls, incense burners, and teapots. It’s as if the master chef desires to share his life with you and not just his food.

After lunch, we traveled a short distance to our next destination to learn about an Usuki tradition that nearly went extinct: Usuki pottery.

How To Make Usuki-yaki Pottery in Japan

The potter Yakushiji-san begins his lesson by brewing us a pot of pour-over coffee. After grinding some locally roasted coffee beans, he makes a pot of fresh coffee using instruments and coffee mugs he created from clay. His workshop is not just about the business of ceramic making but of community and socializing. And, well, Yakushiji-san loves coffee.

The history of Usuki-yaki, the local type of Japanese pottery, is actually a brief one. About 150 years ago, a climbing kiln was built in Usuki to manufacture local ceramics in the late Edo Period. However, the kiln only prospered for about ten years before production began to decline. Eventually, the production of Usuki-yaki ceased entirely and was considered extinct until local artisans sought to revive it.

Today, a handful of artisans, including Yakushiji-san, have workshops producing Usuki-yaki products. It seems the local people were not ready for their own brand of ceramics to disappear.

There are two types of Usuki-yaki, one white and one brown, of which we worked with the latter. The appearance of the brown Usuki-yaki is rough and natural, with elements like iron lending color to it. While it lacks the elegance of fine porcelain, it is a beautiful type of Japanese pottery designed for the rigors of everyday use. Yakushiji-san offered us many different options to make in the workshop, and my traveling friends and I chose bowls and flower vases.

Yakushiji-san gently guided the position of our hands and how to put pressure on the clay to shape it. With his help, it almost felt like I had the skills to make a decent piece of pottery, though I am quite sure he was simply channeling his own skills using my hands as his tools. Regardless of how it was made, I was very proud to have created something presentable enough that would not need to be called “an ashtray” later.

It takes about a month after creating the initial piece for it to be fired and completed. Yakushiji-san can ship the finished product to you anywhere in the world (you pay the shipping fees), so you can participate in the workshop even if you don’t live in Japan. If you can’t wait that long or don’t want to pay shipping costs, finished Usuki-yaki products made by Yakushiji-san are available for sale in the workshop.

After a day of experiencing the traditions and culture of historic Usuki, we headed north where a ryokan run by 30 generations of the same family awaited us in a quiet valley.

Yama no Yu: A Kyushu Ryokan Run for Over 400 Years

The title of Noda Yuka on her meishi 名刺 (business card) says “waka-okami” 若女将, meaning the “young proprietress.” Her family has been running Yama no Yu since the 1500s when it went by the name “Izumiya“. Eventually, Noda-san and her husband will take the reigns from her father, though she is already deeply involved in the ryokan’s daily operations.

Ryokan are the most common forms of accommodations in this part of Oita, offering travelers a comfortable Japanese style room, huge kaiseki meals, and onsen hot spring baths from the famous healing waters that spring from underground all over Kyushu.

One of the first things you will notice about Yama no Yu are the camellias. The camellia motif is part of the ryokan’s design: on pillow covers, wall coverings, and even in the staff uniforms. According to Noda-san, her grandfather felt the camellia was a flower that invoked feelings of friendliness and hospitality, two things he took pride in when it came to the ryokan’s service. Since then, it has become part of the culture, both in decor and the values it represents.

The hot springs include indoor and outdoor baths and a cave bath, all fed with natural hot springs water. Guests can change into yukata loungewear in their rooms and wear it around the facility, to the onsen, and to meals.

Speaking of meals, Yama no Yu provides a feast for dinner and breakfast, the former a kaiseki meal prepared by their meticulous chef. According to Noda-san, he has quite a reputation with the local vendors for demanding the highest quality ingredients and is not afraid to send vendors scurrying to find better products if he deems them unacceptable.

Our meal included a flat stone heated by a firepot on which we grilled marbled slices of local beef and delicately cut seasonal vegetables like sweet potato, pumpkin, and shishito pepper. River-raised yamame sashimi as bright orange as salmon but with a firmer texture. A plate of tempura with mild myoga ginger, shiitake mushroom, and a slice of white fish was complemented with a wedge of local citrus sudachi. A hot pot with soy milk and miso waited for me to add thinly sliced local pork and fresh vegetables to make a hearty soup.

There was more: a salad plate that partially concealed a serving of carpaccio, a creamy bowl of beef stew, a handmade scoop of yuzu sherbert for dessert. The sheer quantity of the meal had my dinner mates and me shaking our heads in disbelief. Yet it was all so delicious, and I felt remorseful about leaving anything behind. In the end, the physical size limits of my stomach overcame my guilt, and I wobbled away from the table and back to my room, where I lay on my fluffy futon, defeated.

The next morning before leaving Yama no Yu, the “young proprietress” Noda-san joined us at the entryway, bidding us farewell and posing for some photos in the noren (traditional fabric dividers hung in doorways, between rooms, and on walls.) As we pulled away, we realized that the reputation of this centuries-old family business would soon be in her hands, and it couldn’t be better protected.

Access To Usuki and Around Oita

While Usuki city is easily accessible from Oita or Beppu via the JR Nippo Line train, getting between various locations in Usuki is easier by car. Yama no Yu is located in Kokonoe, about an hour and a half from Usuki and is a good base from which you can access Kuju Flower Park in Taketa or the Kokonoe Yume Otsuribashi Suspension Bridge. If you plan to tour the area, a rental car is strongly recommended.

Cruise from Kyoto to Kyushu Aboard the Sunflower Ferry

This experience was part of a week-long journey taken by myself and fellow writer Don Kennedy. The unique aspect of the trip was that we spent half the week in the countryside around Kyoto and the second half enjoying the countryside of Oita Prefecture. We bridged the two locations, which are hundreds of kilometers from each other, using the Sunflower Ferry, which provides a luxurious overnight ferry service that feels like a mini cruise in Japan. Learn more about the Sunflower Ferry in the article I wrote about my experience onboard.

More About Exploring Kyoto and Oita

To learn more about rural Kyoto and Oita prefectures, please continue to read the other articles in our series.

Enjoy The Autumn Colors Outside of Kyoto City

Experience Uji Green Tea at a Tea Farm near Kyoto

Kayabuki: The Tradition of Thatched Roof Houses in Japan Near Kyoto

Swords and Samurai in the Kyoto Countryside

From Kyoto to Kyushu: A Mini Cruise on Japan’s Seto Inland Sea

The Natural beauty of Kyushu: Oita Prefecture

The Best of Oita: Usa Jingu Shrine, Beppu Jigoku and Chinetsu Ryori

Unexpected Luxury Awaits You in World-Class Accommodations, Onsen, and Cuisine in Beppu

This article is sponsored by Kinki Transportation Bureau, Kyoto Prefecture and Oita Prefecture.

No Comments yet!