Death. That mystery yet to be solved. That unanswered phenomenon that all cultures try to understand. The path to the afterlife affects every single living being. Where do we go when we die? What do we become? Can the deceased observe us and help us from beyond?

Throughout history, each culture has created a series of collective rituals related to death to overcome pain, loss, and the absence of answers. Death in Japan is a fascinating topic to talk about. With its incredible spiritual background, Japanese culture has a unique way of answering all these questions.

Death in Japan: Its Meaning

Shinto and Buddhism coexist seamlessly in Japan, sharing beliefs like the significance of living beings’ souls. In Shinto, it’s believed every person harbors a kami 神, a deity bound within the body. Upon death, this spirit regains its strength and emerges, requiring care and offerings like food, drink, and entertainment to “survive.”

Death in Japan is seen as a pivotal transition, akin to birth. To ensure a peaceful journey to the afterlife, the deceased and their family must perform specific rituals. The dying person must leave the world in complete peace, free of unresolved issues or negative thoughts, as these could disrupt their path.

This belief parallels Christian confession in its focus on purity, but the Japanese perspective extends further. Harmony and closure are essential, emphasizing the cultural importance of maintaining balance even after life ends. A Japanese can’t leave anything to resolve, no grudge, not even the slightest doubt. A simple negative thought before dying could cause problems for your journey into the afterlife.

Death in Japan and Japanese Morality

When I first explored Japanese culture, I was struck by how differently honor and morality are expressed compared to my own background. This contrast, I discovered, stems from the profound significance of death in Japanese society.

As noted, a deceased person’s spirit requires ongoing support from the living. Why dedicate yourself to elaborate rituals and offerings for someone who has passed? The answer lies in gimu 義務, the moral obligation children owe their parents—a deep sense of gratitude and duty central to Japanese values.

Gimu: The Unsolvable Moral Debt

In Japan, parents give the priceless gift of life, creating an eternal bond of gratitude known as gimu, an unpayable debt owed by children. This moral duty is passed through generations, with repayment beginning after a parent’s death by ensuring they pass peacefully, performing funeral rituals, and continuing offerings of food and drink to honor their spirit.

Fulfilling these obligations brings protection from a sorei 祖霊, a benevolent ancestral spirit. However, neglecting these duties risks turning the spirit into a yurei 幽霊, a tormented soul.

This tradition underpins Obon, Japan’s summer festival for honoring the dead. Families gather to visit ancestral homes, pay respects, and ensure their loved ones rest in peace, making Obon a cornerstone of Japanese culture.

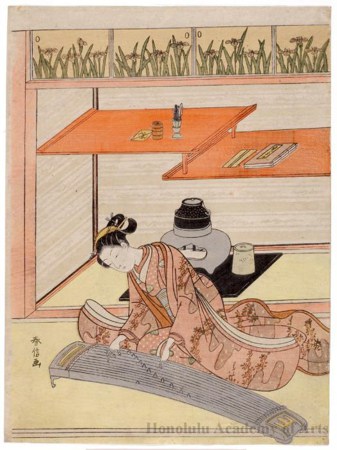

The mix between Japanese social morality and religious superstitions makes Japanese both fear and love their ancestors. This is the reason why, nowadays, most Japanese homes have altars dedicated to their deceased, offering them food, sake, and part of their thoughts. In part, for this moral obligation, for fulfilling that impossible debt and to be protected from all evils.

Heaven and Hell in Japanese Culture

Shinto, Japan’s indigenous religion, introduces the concepts of konoyo この世 (this world) and anoyo あの世 (the hereafter), emphasizing their close connection. While reaching the afterlife is challenging, movement between worlds becomes easier once there. For many Japanese, the presence of ghosts feels natural, as spirits pass through yominokuni 黄泉の国, a Hades-like realm with an entrance said to be at Yomotsu Hirasaka in Shimane Prefecture.

Buddhism’s arrival brought new perspectives on death, including cremation and the idea of Jodo 浄土, the Pure Land paradise led by Buddha Amida. It also introduced jigoku 地獄, a unique Japanese hell with countless realms, each with punishments tied to fire or ice.

Japan’s volcanic terrain inspired beliefs about hell’s gates, with locations like Beppu’s hot springs, Noboribetsu in Hokkaido, Mount Tate in Toyama, and Mount Osore in Aomori considered entrances. Even Senkoji Temple in Osaka offers a depiction of heaven and hell.

Death in Japan Throughout History

The ancient Japanese had a high level of spirituality. They used to assume that their ancestors were the ones who created the natural disasters on the island. They imagined them as strong souls with great powers that dominated the spirits of nature. As if that weren’t enough, death had already great importance during the Jomon Period 縄文時代 (14,500 BC – 300 BC), as some ancient tombs demonstrate the performance of specific rituals.

During the prehistoric Yayoi and Kofun periods, there was a clear evolution. In the Kofun period, the inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago began to change their funeral concept. We can see this as the shapes of their tombs were modified. Nowadays, you can see their legacy in different places like Osaka.

Buddhist Death: Heian Period

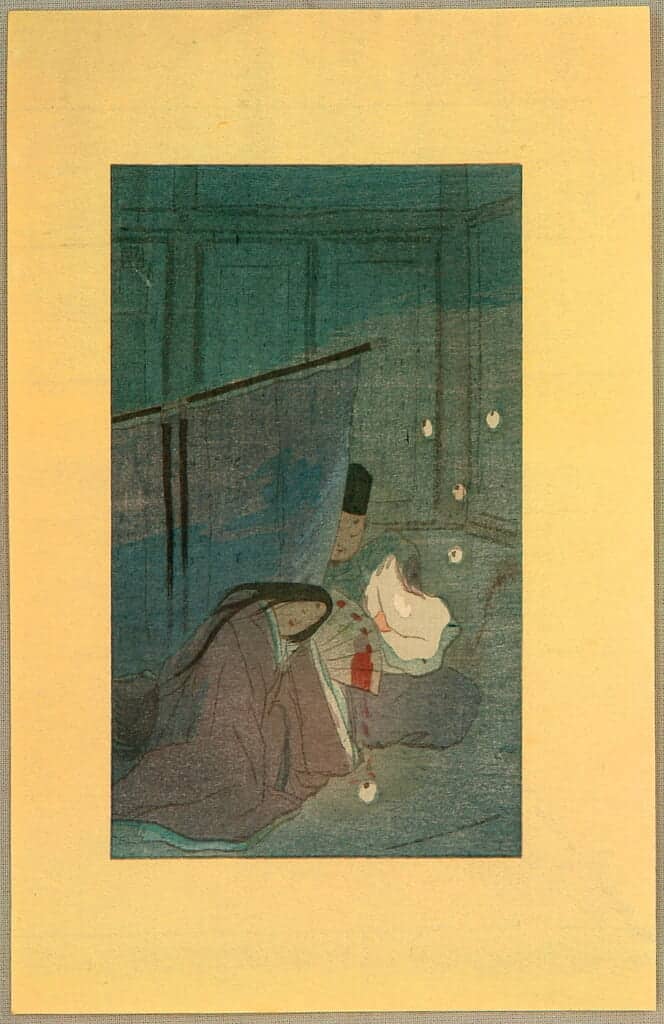

Buddhism became deeply ingrained in Japanese society during the Heian Period (794–1185), introducing profound changes to beliefs about death and the afterlife. Funeral customs among the upper classes grew into elaborate rituals, with a focus on dying in the purest state possible to secure eternal peace.

One notable practice involved isolating the dying person in a stimulus-free room to avoid distractions or impure thoughts. Wealthier individuals often had a zenchishiki 善知識, a caretaker who recited sutras to help maintain perfect concentration.

By the end of the Heian Period, cremation had gained prominence as a significant Buddhist ritual, symbolizing a union of the deceased’s body and soul with Buddha. Initially practiced by the elite, it became widespread during the Kamakura Period.

Honorable Deaths in Japan: Seppuku and Harakiri

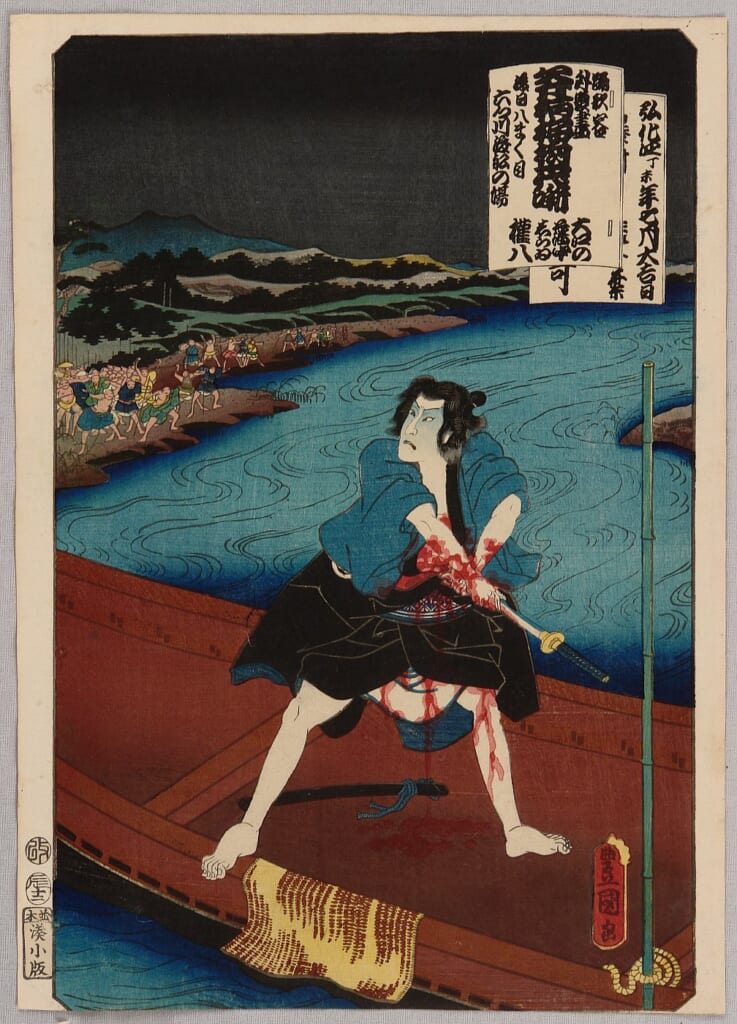

During the samurai era, it was introduced the practice of seppuku 切腹, also called harakiri 腹切り, a ritualized and honorable method of suicide. This act was often carried out when a samurai failed a mission or was defeated in battle, symbolizing redemption and dignity.

The process involved using a sword to cut into the abdomen, a deliberate choice reflecting the belief that the soul resided there. Through this act, the samurai aimed to free themselves and die with peace and honor, avoiding remorse or disgrace.

Seppuku wasn’t exclusive to samurai; commoners could also be condemned to this method of death. Although it may seem grim by modern standards, during that era, seppuku was considered the most dignified way to die. It represented courage, self-discipline, and the ultimate act of self-respect. For those who faced death, performing seppuku was regarded as a final and honorable gift to oneself.

New Perspectives of Death

The meaning of death evolves as society does. Nowadays, life expectancy in Japan is one of the longest in the world. This is why people, after retiring, have time to enjoy their remaining decades and to think about death.

Is it Possible to Die in Peace in Japan Nowadays?

Death in Japan has long been surrounded by strict rituals, leaving little room for personal choice in one’s final days. However, modern attitudes occasionally clash with ancient traditions. The desire to “die in peace” is still deeply rooted in Japanese culture. Many prefer to pass away at home rather than in a hospital surrounded by machines. This reflects a longing for dignity and serenity in one’s final moments.

Organ donation is another area of cultural tension. Traditional beliefs emphasize the importance of remaining whole until cremation to ensure a harmonious afterlife. These beliefs often deter organ donation, as they conflict with religious views on eternity.

Additionally, family plays a pivotal role in these decisions. In Japan, relatives have the ultimate authority over the dying person’s fate, further complicating matters when modern preferences diverge from traditional expectations.

Death is no Longer a Community Task

In ancient Japan, funeral rituals were a community responsibility, fostering unity as members collectively managed preparations and mourning. However, modern generations are shifting away from this tradition. Many now hire professionals to handle the process, leading to a loss of ritual knowledge and a decline in the communal bonding once central to these events.

This shift reflects broader societal changes, altering the symbolic and cultural significance of death rituals in Japan today.

We can’t know where we go after death, but we can firmly believe in something while living. In Japan, they think that the dead never leave us and take care of us or, on the contrary, disturb us. Even though we live in a world surrounded by new advances in modernity, there is still a spiritual world with beliefs rooted in tradition. If tradition and modernity can go hand in hand, why not the world of souls and the world of the living?

For this article, I used the book Yurei: The Japanese Ghosts by Zack Davisson as a reference.

No Comments yet!