The fabled Momotaro Peach Boy may have killed a few ogres, but Okayama (岡山) is steeped in many timeless ingredients for sightseeing and enjoyment: peaches, pottery, Nihonga paintings, old-style sushi, remote mountain onsen, and moon-viewing pleasure gardens.

Korakuen: A Peaceful Walk Through One of the Three Great Gardens of Japan

If the modern pulse of Okayama lies in the lively neighborhood of high streets and shopping arcades that surround the central train station, its historical core is indisputably Korakuen gardens (後楽園). The famous Edo-period garden was originally commissioned as a peaceful daimyo resort by Lord Ikeda Tsunamasa and completed in 1700 and has been open to the general public since 1884. Today, the garden buzzes with locals, tourists, birdwatchers strolling, or commuting across and around it on either side of the Asahigawa River.

Korakuen is popularly known as one of Japan’s Three Great Gardens (日本三名園) since the ranking first appeared in a photo book for foreigners in 1904. Korakuen survived significant damage from a 1934 flood and 1945 war bombings and has been faithfully preserved over the years thanks to detailed plans and illustrations documented by the original Ikeda clan. Inside the garden are sprawling green lawns, dense groves, colorful blossoms, and tranquil paths. Reflective koi ponds are interwoven with thoughtfully placed rest houses, stepping stones, and wooden bridges over streams.

View from Yuishinzan Hill Sawa-no-ike Pond

Meandering through the garden — which also includes the remains of an equestrian ground and an archery range — it’s easy to imagine a feudal lord’s leisure activities during more peaceful times. Every spring, Korakuen hosts tea picking and rice planting festivals. Every autumn, traditional Noh theater performances are held at the reconstructed open-air stage in honor of Lord Ikeda’s affinity with the 14th-century art form.

In one corner, endangered red-crowned cranes (タンチョウ鶴) live inside a dedicated aviary. As Japanese symbols of luck and longevity, cranes roamed free at Korakuen from the Edo period until they died out after World War II, then were reintroduced in 1956. A few times a year, these majestic birds are let out on scheduled morning strolls within the garden grounds and during New Year’s Day for a ceremonial flight.

Regal Views from Okayama Castle

Visitors can also walk along shaded paths outside the garden, especially around its South Gate, before crossing the pedestrian Tsukimi Bridge to Okayama Castle (岡山城). Like many black and white tenshukaku (天守閣, castle towers) in the region, its architectural style is characteristic of the Azuchi-Momoyama period in the late 16th century. The distinctive black weather boards that protect its outer walls give it the nickname of Ujo (烏城), where Okayama’s “Black Crow” Castle contrasts with neighboring Himeji’s famous “White Egret” castle.

Tiles of the reconstructed Gate at the top of 61 Steps bear the Ukita clan’s Kiri (paulownia) coat of arms. Gold Shachihoko (mythical carp with the head of a tiger) and 5th-floor views.

Okayama Castle was founded by Lord Ukita Hideie in 1597 and eventually expanded to include a salt warehouse, 35 turrets, and 21 gates. In 1869, the main buildings became the property of the Meiji government and had been preserved as national property until an air raid on June 29, 1945, burnt most of the castle complex. The only surviving building in the central area was the 1620 Tsukimi Yagura (月見櫓, Moon-viewing Turret), that feature special eyelets for spotting enemies embedded on the northwest walls.

Okayama Castle’s present 6-story, 21-meter-tall tenshukaku was reconstructed in 1966, along with three main gates. The main building now serves as a museum, equipped with an elevator, cafe, shop in the basement, and a studio to craft your own Bizenyaki (備前焼) pottery. But it also exhibits a replica of a Lord’s chamber and artifacts such as swords, calligraphy, lacquerware, ornate stitched armor, and preserved parched letters written to the castle’s sitting lords. The regal lookout views are from the 5th and 6th floors.

Art and Design at Yumeji Art Museum

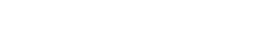

Just north across the river from Korakuen is a more contemporary landmark of Okayama: Yumeji Art Museum (夢二郷土美術館), dedicated to the works of Takehisa Yumeji (竹久夢二), Japan’s most famous Romantic artist of the Taisho period (1912-1926). Easily recognizable by the weathercock on its roof, the old Korakuen train station was renovated and opened as a museum in 1984. Despite the prolific artist’s European influences and cosmopolitan designs, Yumeji remained loyal to his roots in Okayama, where he was born in 1884.

A self-taught painter, poet, illustrator, and graphic designer, Yumeji gained sudden fame after winning first prize in Chugakusekai (中学世界) magazine’s illustration contest at age 22. He went on to design and publish his own books of poetry and drawings for book covers, newspaper caricatures, magazines, postcards, and music scores, often juxtaposing ultra-modern graphics with traditional Japanese elements. At the same time, Yumeji developed the Nihonga (日本画, Japanese style) illustrations of Western-inspired bijin (美人, beautiful women) for which he is best known, in oil paintings, watercolors, woodcuts, and other prints.

Yumeji’s print designs, illustrations, and books Yumeji’s illustrated poetry books (1918-1919) A room featuring Yumeji’s famous Tatsuta Hime (竜田姫, autumn princess)

The Yumeji Art Museum has a total collection of about 3,000 artworks and documents, lovingly researched and preserved by three generations of collectors and museum directors. Several hundred works are digitized and viewable in extreme detail on a large screen, while thematic exhibitions are renewed each almanac season to spotlight a particular aspect of Yumeji’s body of work.

The museum mascot, Kuronosuke Drawings by Yumeji

Since 2017, the museum has a mascot: Kuronosuke (黑の助), a black cat who was rescued from a busy intersection in front of Korakuen, and who uncannily resembles Yumeji’s original illustrations. Across the garden, the newly opened Art Café and gift shop extend Yumeji’s world to sell original prints and products in a gourmet setting. In addition to original sweets, the café serves Michelin-starred chiyagyu (千屋牛), a luxury beef from northern Okayama prefecture.

Gustatory Delights of Okayama Old-Style Sushi

Just west of Okayama station, near the Hokancho shopping arcade, the Japanese sushi restaurant Fukuzushi (福寿司) specializes in sawara (鰆, Spanish mackerel). According to the chef, sawara is the defining element of barazushi: a luxurious style of sushi made in homes around Bizen, Saidaiji, and Okayama from the early Meiji period to the 1930s. A scattering of raw fish and other ingredients laid on top of and mixed into vinegared rice is the Barazushi signature. Unlike chirashizushi, which features popular fish such as salmon and tuna, barazushi’s ingredients are much more varied and subtle—with no soy sauce in sight.

Chef Kubota makes Bizen Barazushi (備前ばらずし) the old-fashioned way, as a “faithful reproduction” of the historical dish, using only fresh, natural, regionally sourced ingredients. Discovering it for the first time, I was captivated by the luxurious combination of tastes and textures presented in the giant clay bowl: vinegary sawara (Spanish mackerel) and mamakari (Japanese sardinella), lemony kotai (small sea bream), salty anago (saltwater eel), wrinkled mogai (algae shellfish), crispy lotus root, chewy gobo burdock root, crunchy green beans, juicy gourd, spicy pink ginger, soft ginkgo nuts, succulent shiitake mushrooms, tender taro stems, and one whole chestnut.

Vinegar is a fundamental flavor in the dish, and the chef advises to begin eating anywhere you like and to chew slowly to give each ingredient time to permeate your palate. I finished my meal by nibbling on delicate fern leaf, which left tangy-sweet flavors on my tongue.

Hot Spring Baths in a Mountain Onsen of Okayama

Less than an hour north of Okayama station by train is the rural village of Takebe that straddles the Asahigawa River up in the mountains. There, rice paddies abound, and wildlife thrives — hawks soared overhead, a white crane posed in the middle of a yellow field, a swan floated quietly on the river, and turtles basked on the rocks. The main road is flanked by fields and houses on either side, a path that penetrates the forest, and a promenade along the riverbank.

When the locals aren’t busy tending to their land, they can also enjoy natural hot springs. The intimate Takebe Yahata Onsen (たけべ八幡温泉) offers several different types of baths, including gensenyu (源泉湯), where hot springs get drawn directly from the source, rather than using recycled spring water. There are two square rotenburo (露天風呂, open-air baths) and four indoor baths of varying styles and temperatures, including the neyu (寝湯) where you can recline with a view of the patio.

Neyu (寝湯) Rotenburo (露天風呂) Rotenburo on the patio

Spend the night in a traditional tatami room, and you will be rewarded in the morning with a sumptuous Japanese breakfast as you contemplate the lush landscape. If you want to soak your feet, there is also a free ashiyu (足湯, foot bath) outside the building, just above the river.

Arriving in the evening, I relished in the sudden stillness of the crisp mountain air outside the train station and enjoyed ambling across the river’s many narrow bridges. The spectacular firefly mating season may have ended, but I could still hear the crickets. On a clear night, remember to gaze up at the sky. Even if you can’t view the moon, you will certainly see the stars.

How to get to Okayama

Okayama is a dedicated stop on the Tokaido shinkansen line, just a little over 3 hours from Tokyo, 1 hour from Kyoto, and 35 minutes from Hiroshima. It is also accessible on other train lines using a Japan Rail Pass.

Okayama’s pleasures are rich and varied, spanning styles and centuries back to feudal Japan. Whether you seek historical sightseeing in the heart of the city or a peaceful soak in a remote mountain onsen, follow the fabled Peach Boy to embark on your own personal adventure.

Sponsored by Okayama city, Okayama